Canoso’s past with 3D printing stretches back to grad school where he got his feet wet with a high-end, industrial 3D printer.

“It was pretty cool to use that to prototype projects that I was working on, but the problem is that it was really time-consuming, really expensive.” He recalled the beauty and also frustration of working with the high-quality, powder-based 3D printer. “You’d go to grab your model out of the printer and there’d be nothing there because there was some error in the mesh.”

At Willow Garage, the robotics research lab out of which Savioke was born, they had a similar 3D printing setup to Canoso’s university experience.

“We had a lot of resources at the time, so we could afford to get a really expensive printer, and we thought that was a good choice.” But Canoso explains that the process was time-consuming, parts took a lot of post-processing to get a good finish, and oftentimes they would warp.

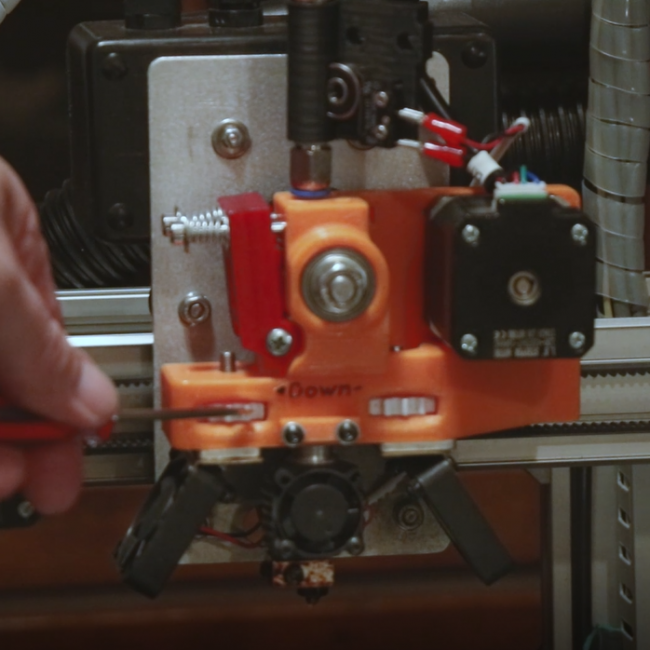

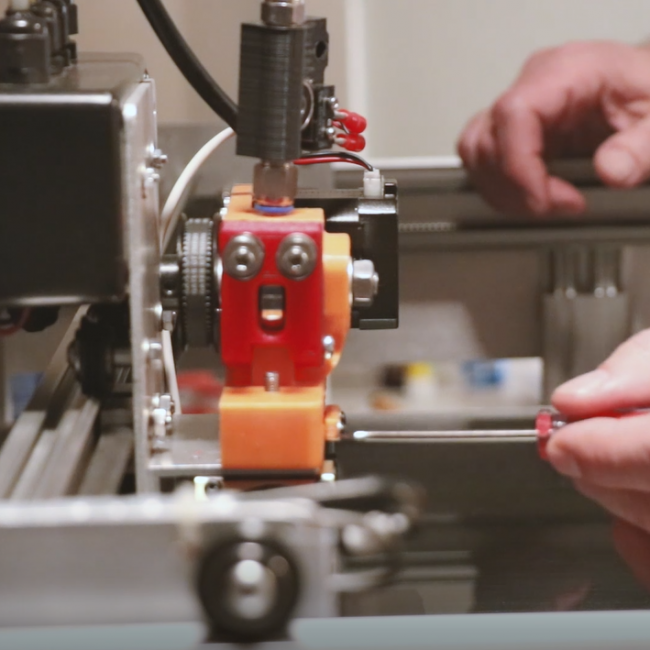

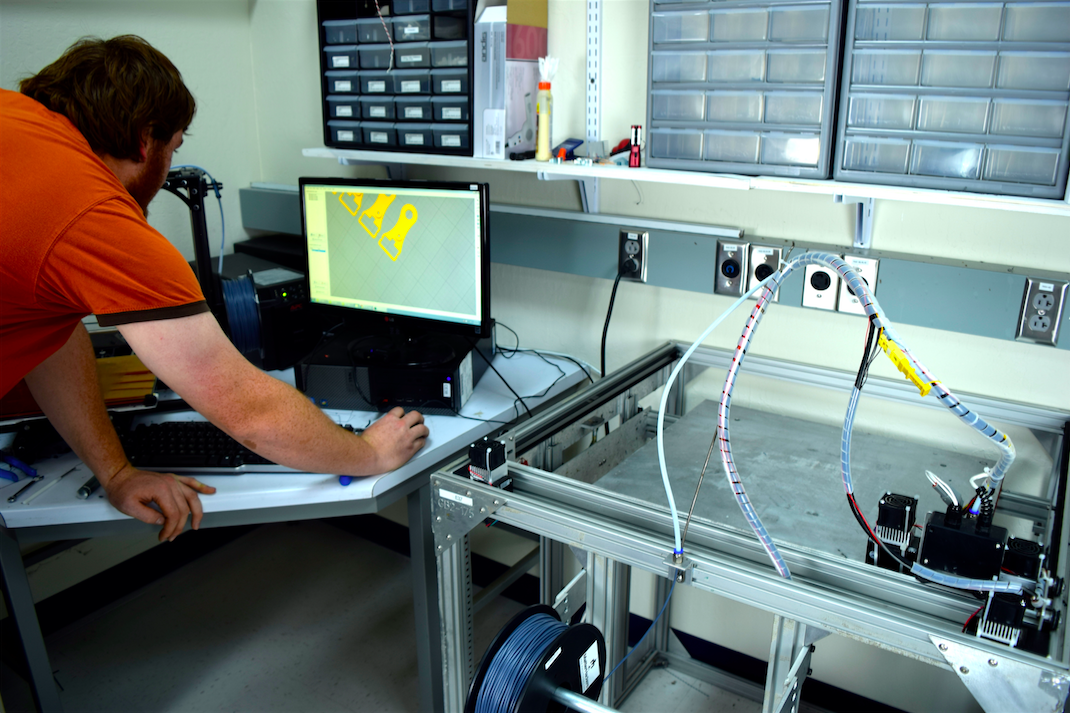

“It turns out,” he says, “that as an industrial designer that’s doing a lot of prototyping, FDM is actually a really great process.” From the material options, to limited post-processing and minimal warping, they found it to be ideal for robot prototyping.

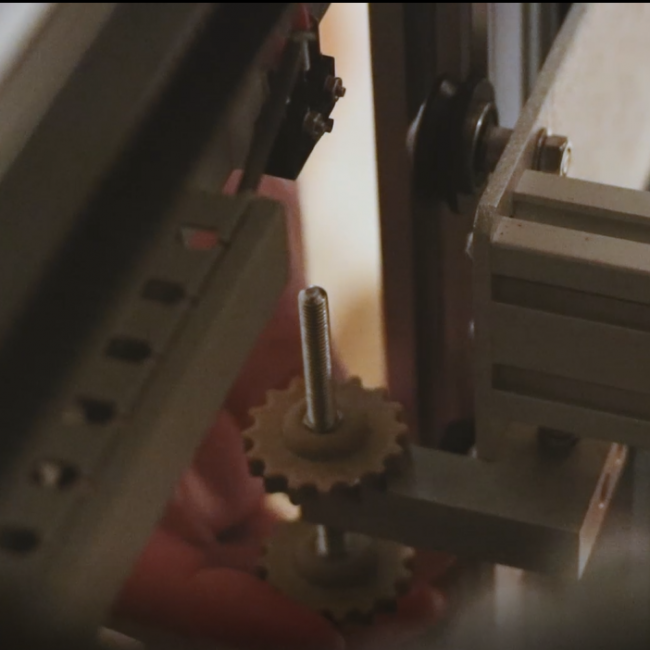

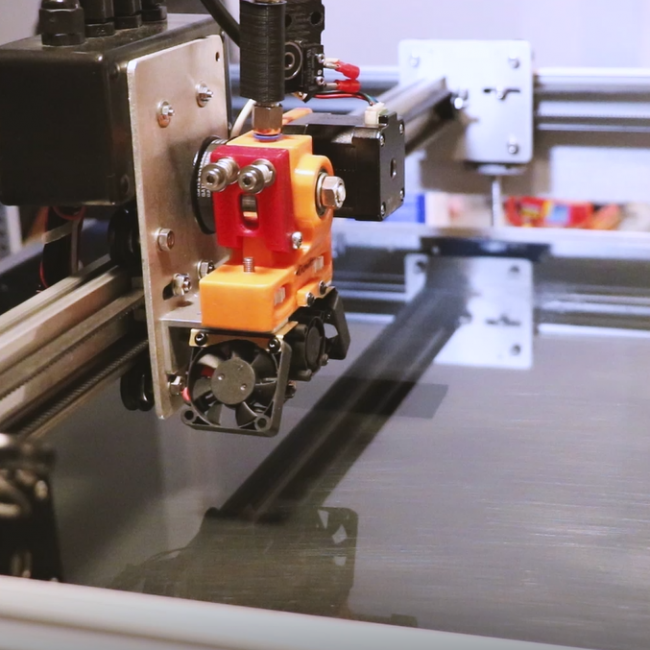

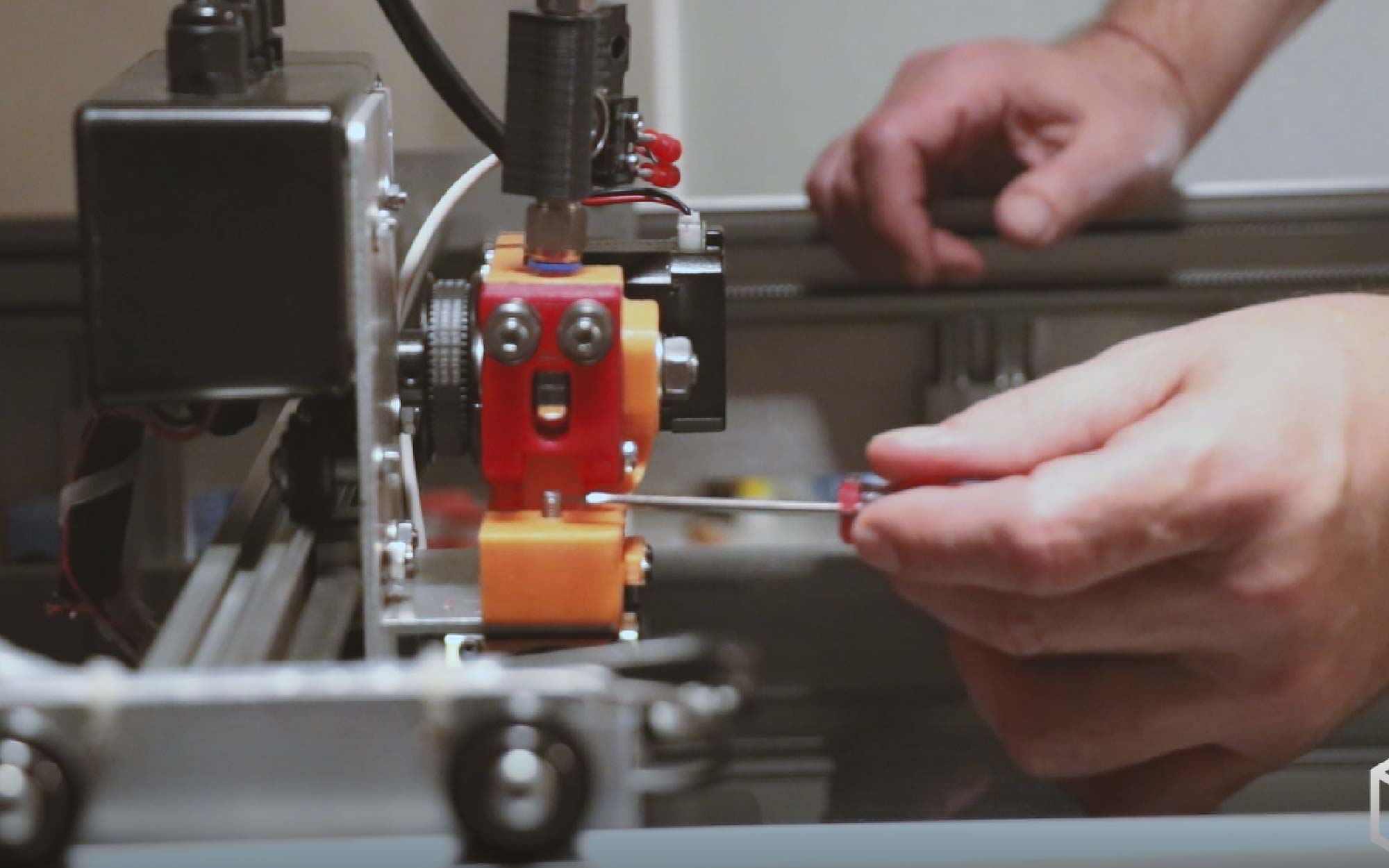

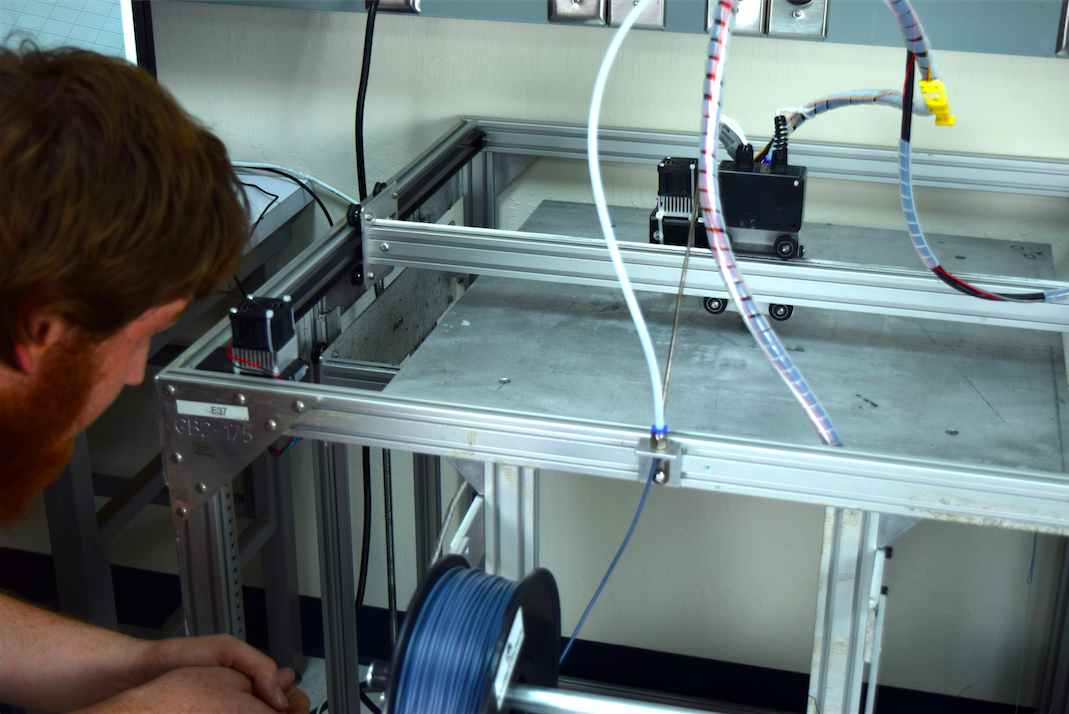

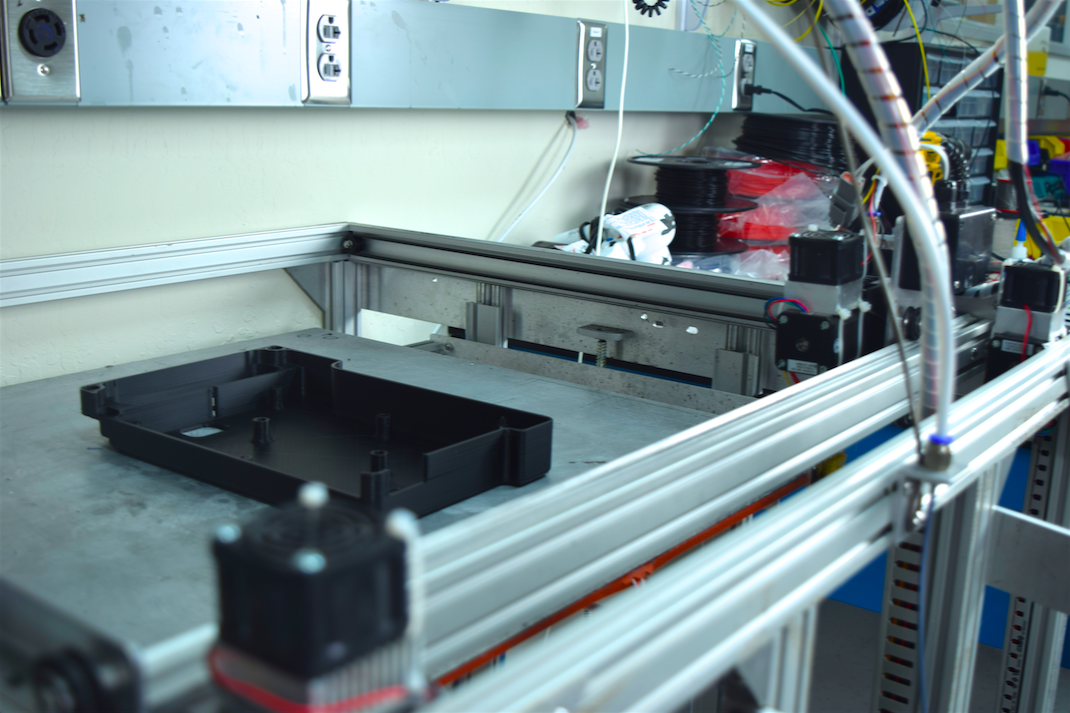

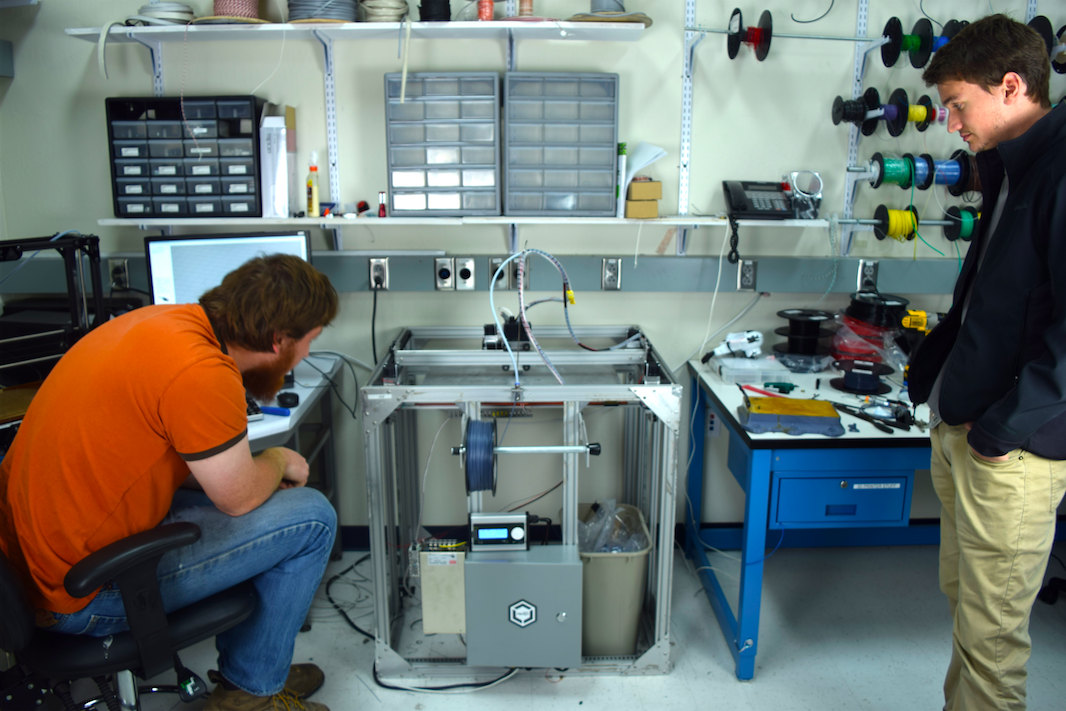

At Savioke, they began the prototyping stage with foamcore, ultimately graduating to CAD and 3D printing when they began to nail down the design of the robot. When they outgrew the build volume of the desktop printers they were using, they began searching for something that could accommodate the two-foot-plus-tall shell of their robot.

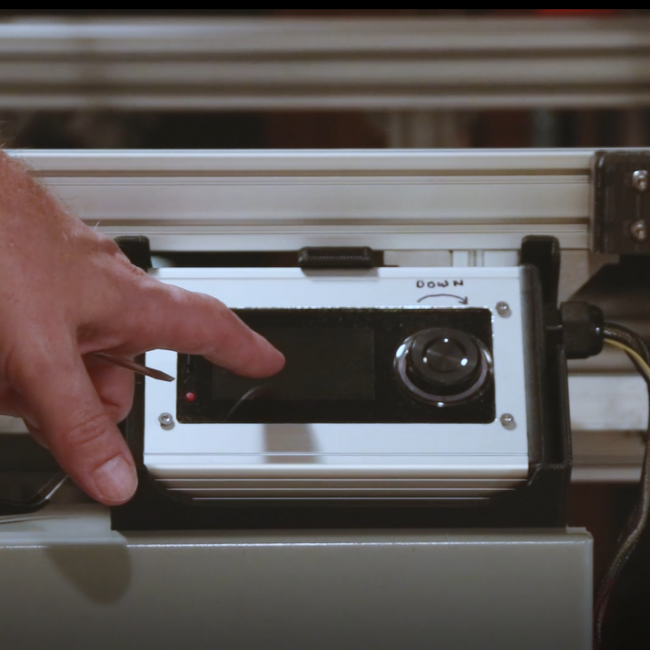

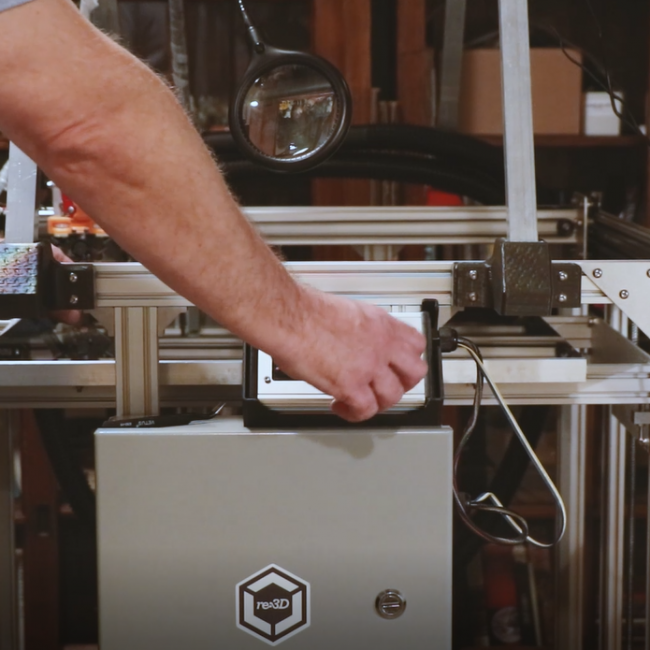

“That’s when we saw the Gigabot show up on Kickstarter,” Canoso recounts, “and we were like, ‘Oh my God, that’s really what we need.’”

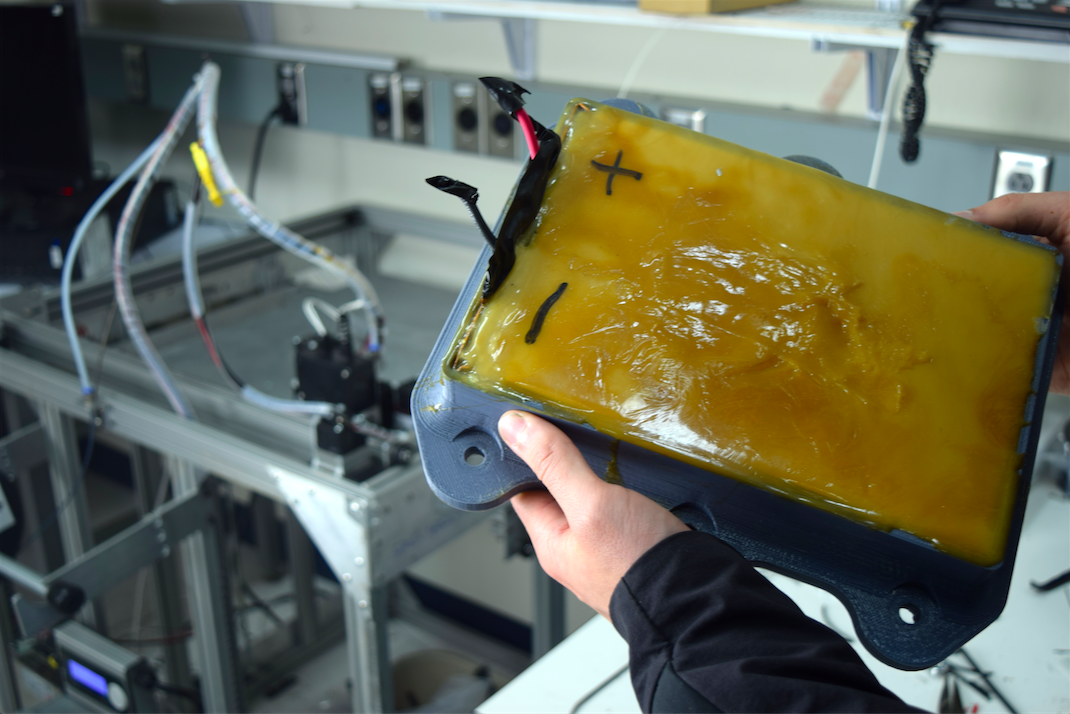

For the first batch of prototypes for hotel pilots, Savioke used Gigabot to print the full outer torso panels of the robots, achieving a final-manufactured look through some in-house post-processing. “The impression we consistently got is that we used a more elaborate process,” Canoso commented.

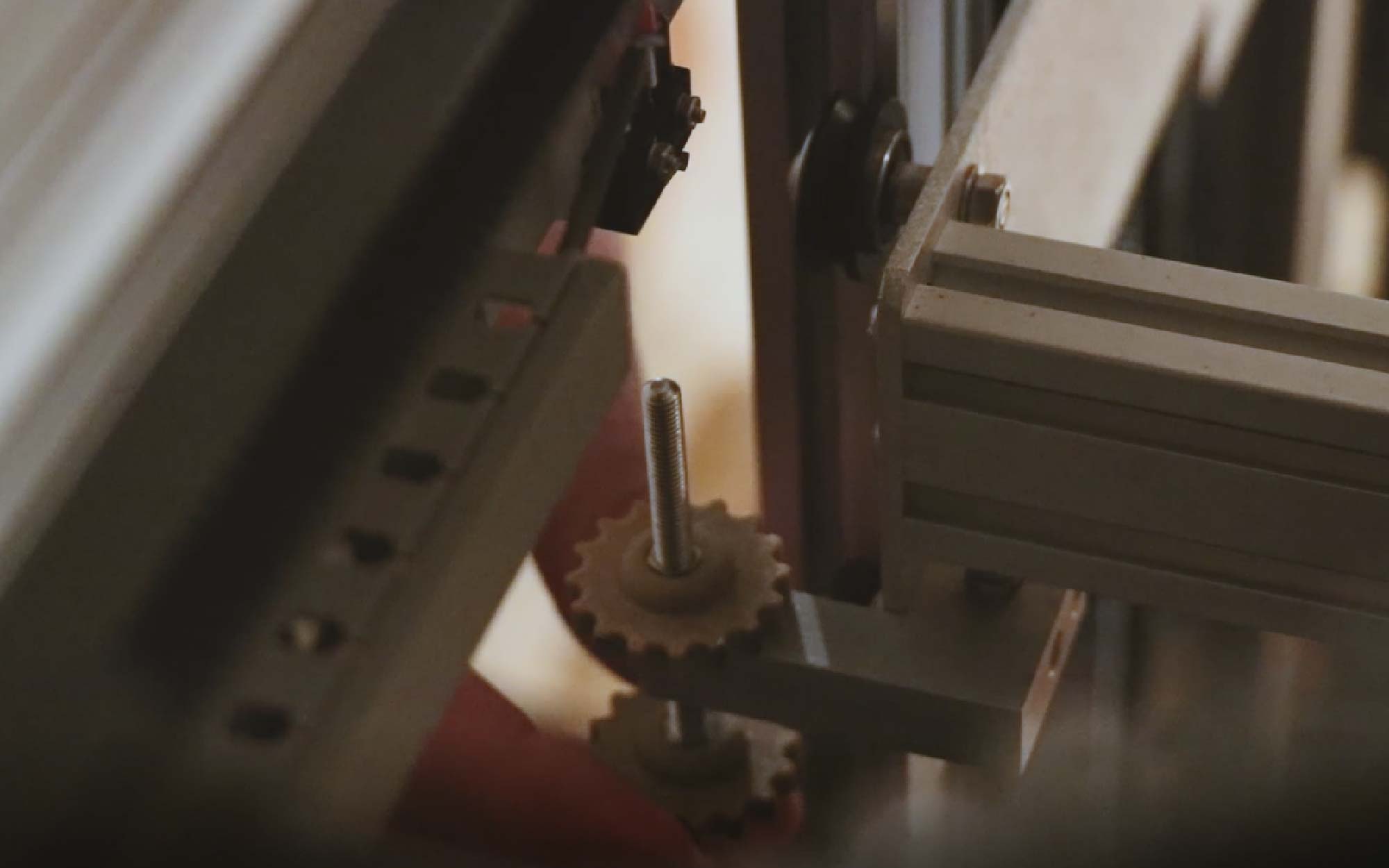

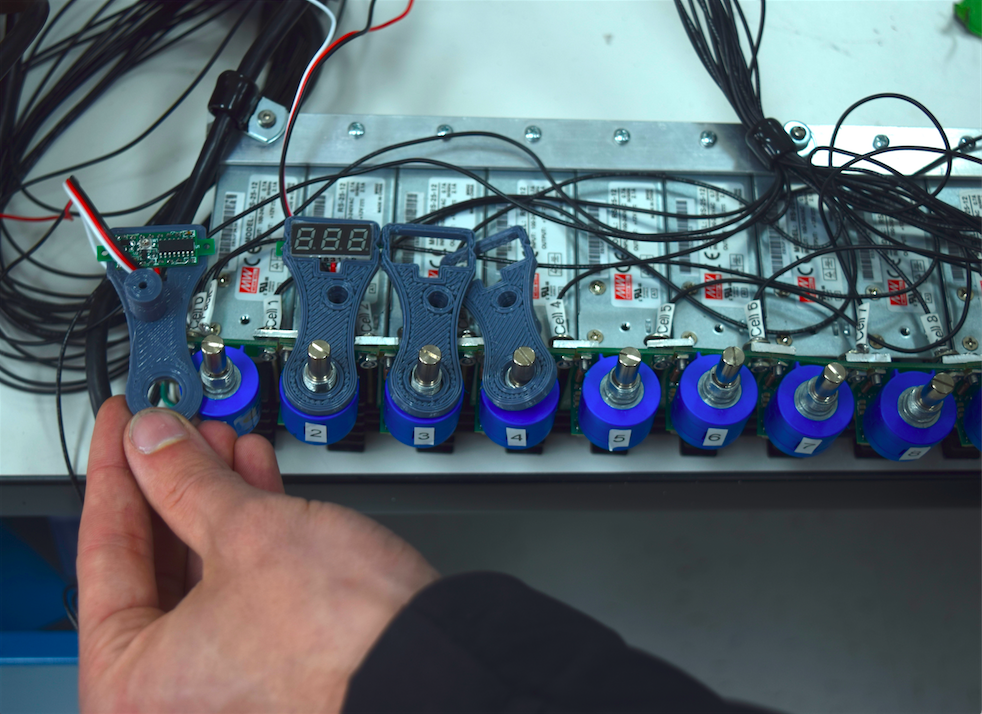

They also use Gigabot to print the entire bottom portion of the robot: a top and bottom piece which encase the mechanical base. “Those pieces were printed in one shot, which was awesome,” Canoso remarks. “[Gigabot] allowed us to just iterate as fast as we needed to.”

To date, Savioke has completed over 15,000 fully-autonomous deliveries, and is expanding to more hotels in the coming months.