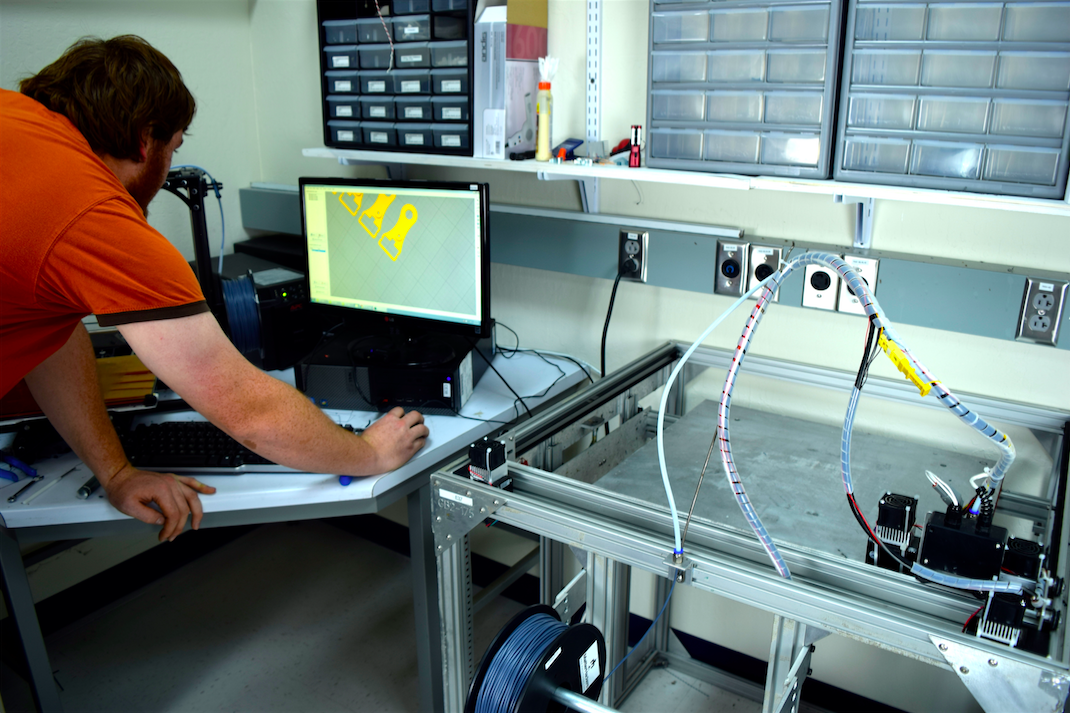

“I got into 3D printing while I was in college doing my electrical engineering degree. One of the things that really got me interested in it was being able to make a box for the electronics projects that wasn’t made out of cardboard and duct tape, which is kind of a trademark of most EE students.”

This is Chase Nachtmann, a Systems Engineer at Farasis Energy.

“That kind of sparked my interest in working with 3D printers, because it’s a way of designing things…and having them come out exactly the way that you want.”

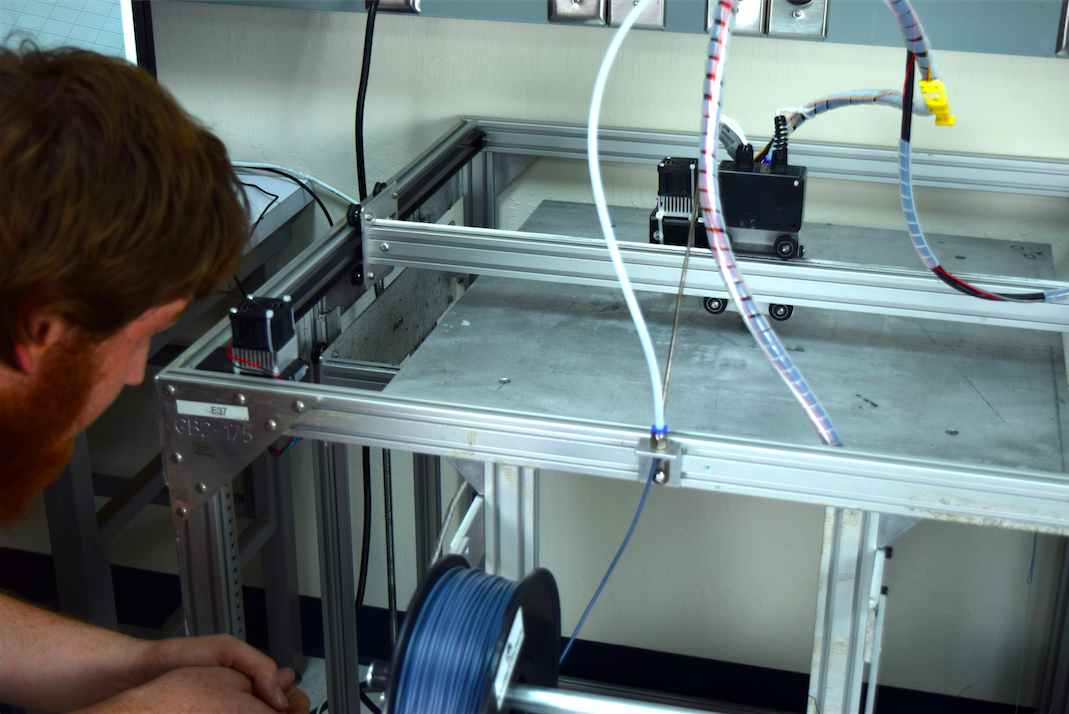

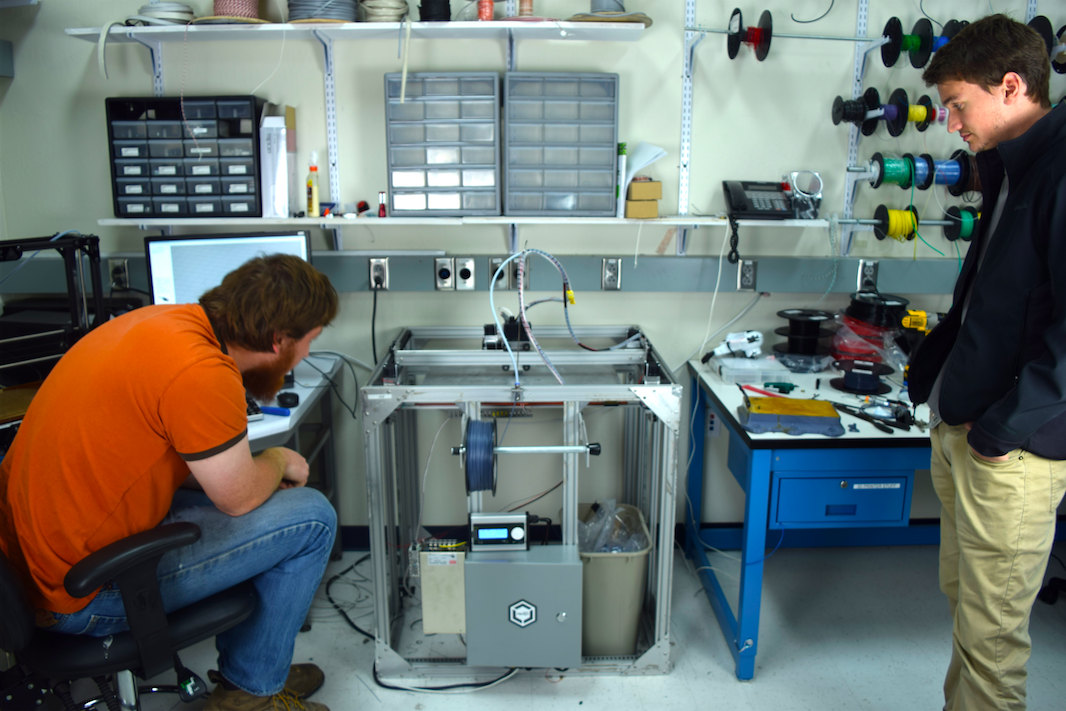

Nachtmann ended up managing the high-end industrial 3D printer at his university, and has now put this knowledge to use post-graduation.

Farasis, based out of the San Francisco Bay Area, makes lithium ion batteries for electric vehicles. They use Gigabot to print parts for a variety of applications throughout their battery pack development process.

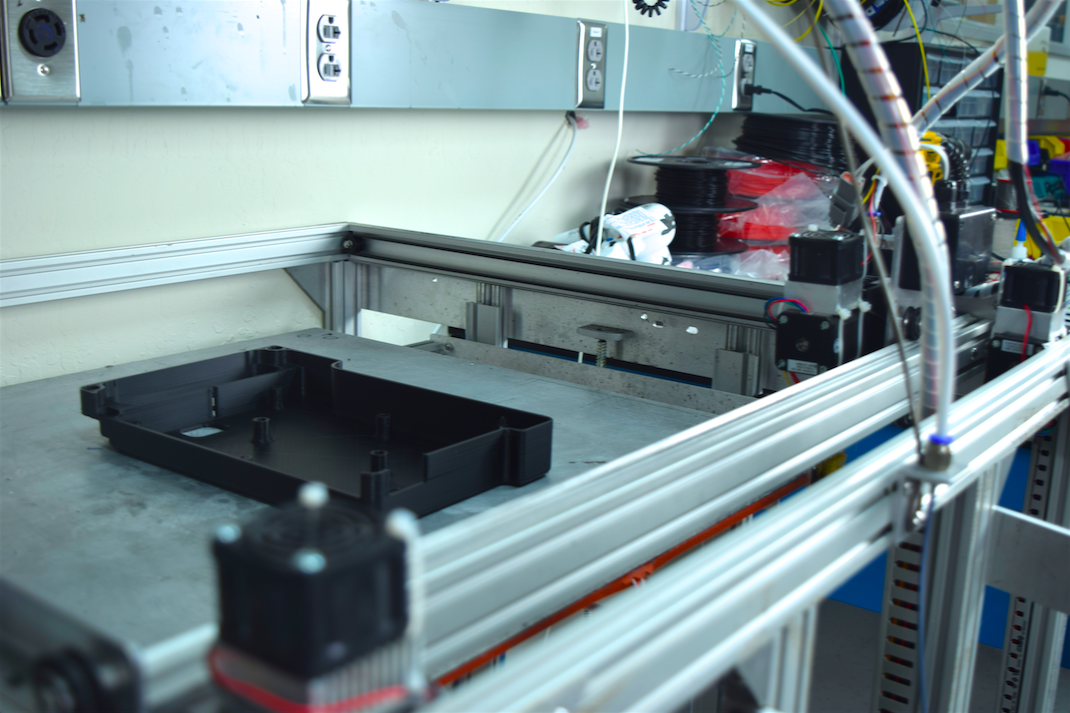

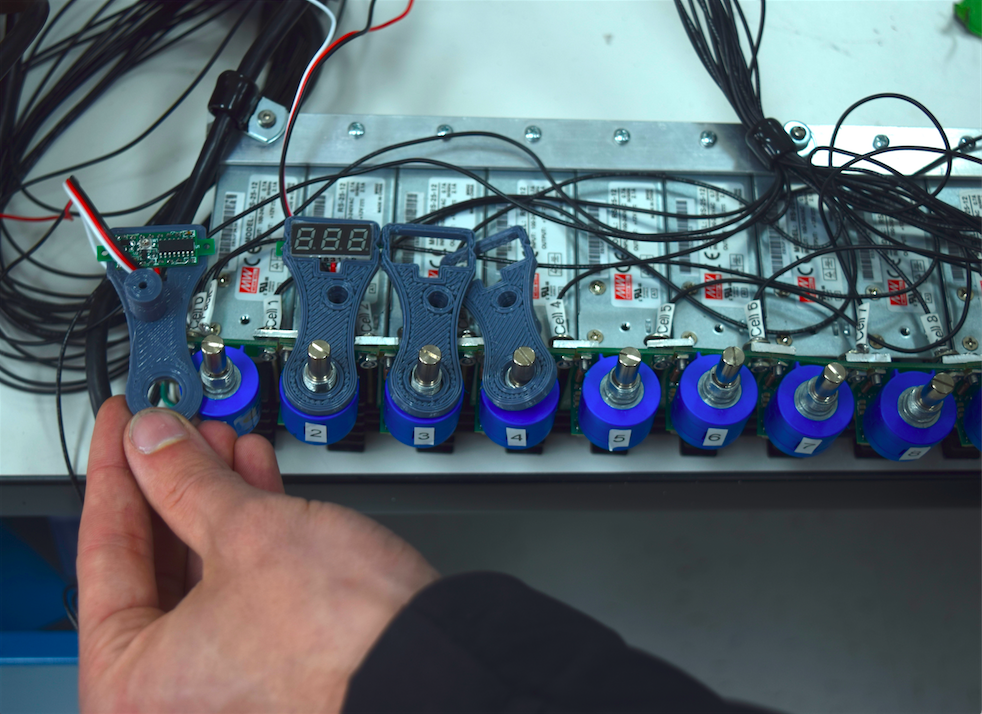

Part of that process involves bolting their pack onto a shake table for testing, which puts it through the ringer by vibrating at a punishing 90 G’s sinusoidal in each direction. This particular piece of equipment is pricey to rent time on.

“It’s very expensive, and it costs a lot per hour,” Nachtmann explains. Jackson Edwards, an Applications Engineer at Farasis, jumps in – “Four hundred and fifty dollars.”

Nachtmann continues, “ When you’re doing a custom-shaped box, at least one hour is just spent bolting it onto the table in a secure fashion.”

This is where their Gigabot comes in.

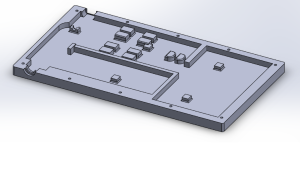

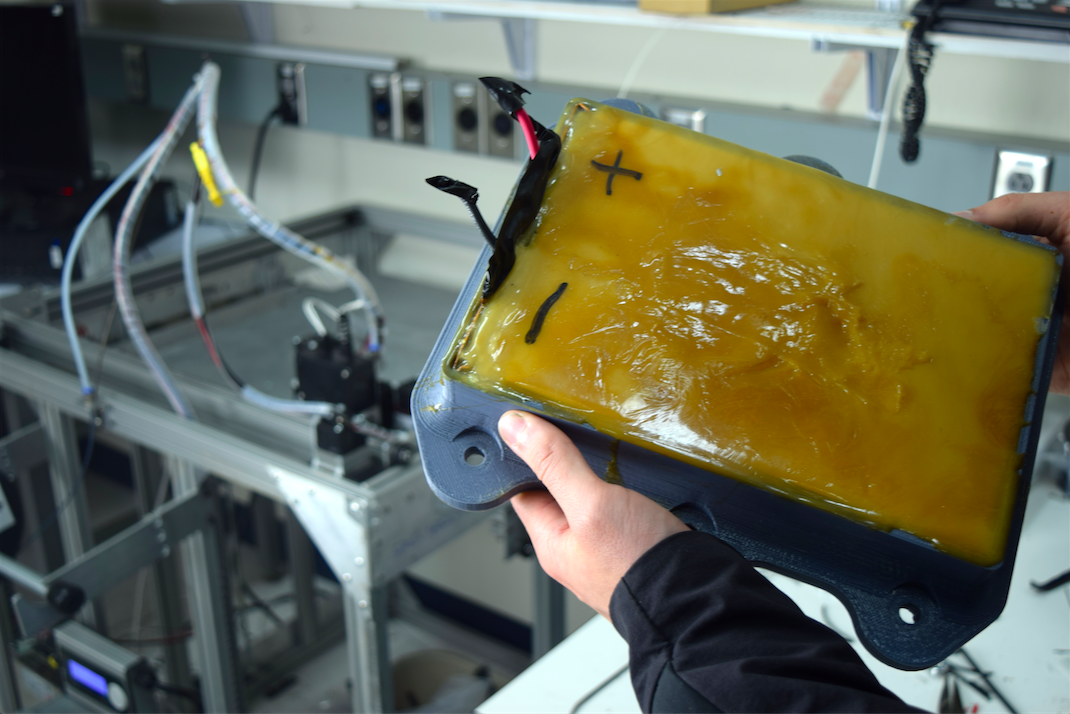

“By printing it, we have a custom box that has the mounting holes already integrated into it – we’re saving a lot of money that way – and we’ve found that printing it was definitely strong enough after we filled the inside with an epoxy body compound,” Nachtmann says. “It saved a significant amount compared to having it machined out of aluminum.”

This machining process was their only option prior to getting a 3D printer. Edwards recounts the process of shopping around for the most affordable option. “We were quoted between two and five thousand dollars for the piece of aluminum, and it also had a 2 week lead time,” he recalls. “Having the ability to make these fixtures in-house is a huge help.”

Contrast this with what it costs them to make the 3D printed version, an extremely dense, 100% infill piece, and it’s a no-brainer. The printed piece uses about five pounds of filament, bringing their cost of printing a custom box to just under $100. On top of that, there’s no lead time: it’s something they can do in-house as needed.

The Product in Action

One of Farasis’s battery packs’ big applications right now is electric motorcycles.

“We just recently completed a build for Brammo’s Isle of Man motorcycle,” says Edwards. “The bikes performed flawlessly and everything went great.”

Another notable name on their customer list is Zero, known for their high-performance electric motorcycles.

“They are right in the middle of their build year right now, making 17 bikes a day,” Edwards explains. “Going to a production-level status with them is pretty fun.”

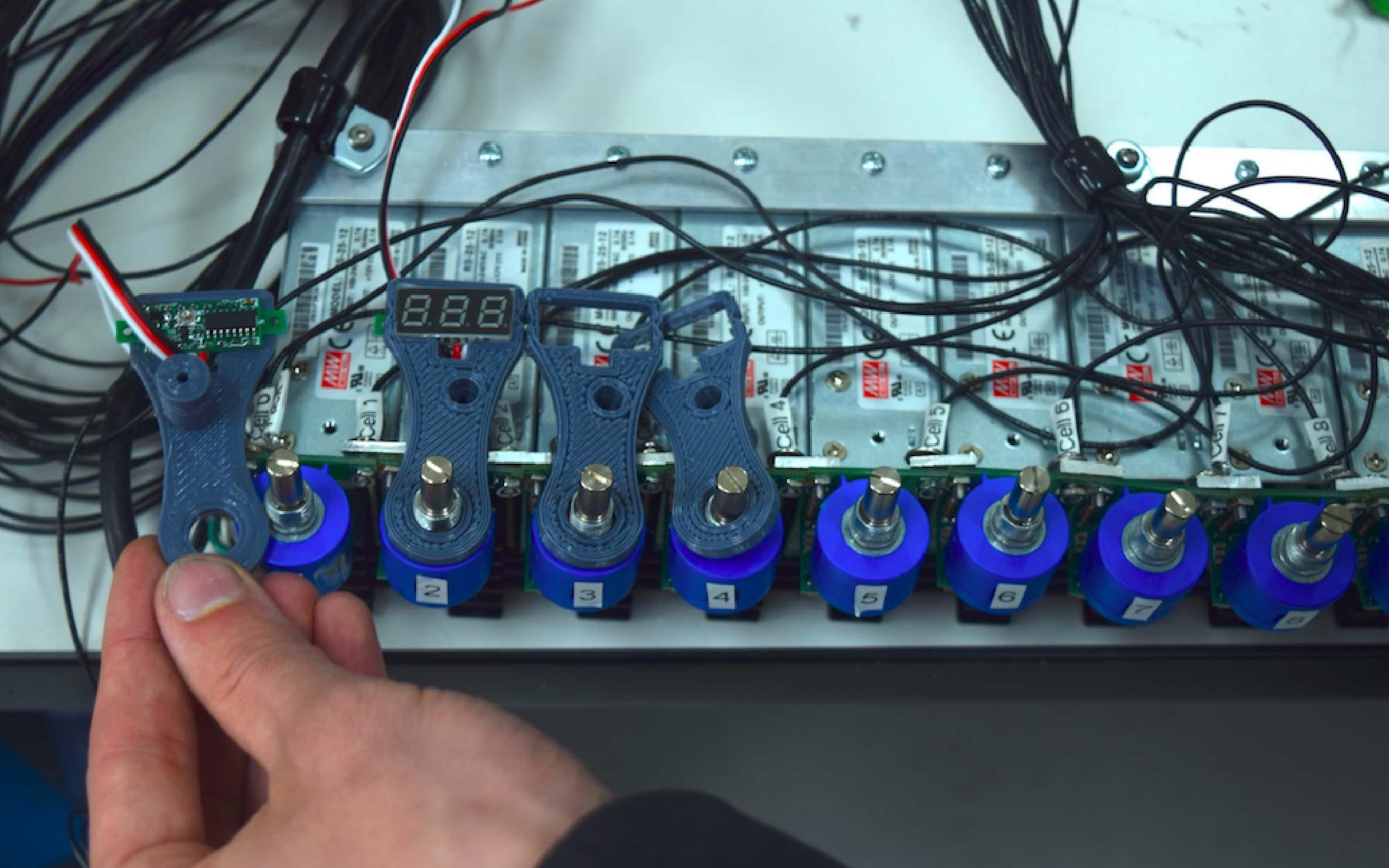

Zero’s bikes use somewhere between 56 and 140 of Farasis’s battery cells, and the Farasis team has also made some 3D printed test fixtures and parts for their validation builds.

As a true sign of someone in love with their work, Jackson proceeds to wheel out a Zero bike of his own from the back of the office.

“I commute from the Santa Cruz area,” he explains. “I used to commute from Aptos, which was 67 miles one-way…but now I’m a little closer and it’s only a 50 mile trip.”

He explains that the bike has a range that would allow it to do the entire round-trip on one charge, but as he puts it, “it’s nice to have a little bit of headroom.” He opts to plug in at the office while he works.

I get my motorcycle-fantasy fix vicariously, so I leave with the question: how fast does this thing go?

“The fastest I’ve had this one is 105,” Jackson reveals. “It’s a heck of a lot of fun.”

Morgan Hamel

Blog Post Author