On April 9, 2019 re:3D hosted the first annual FFF1: Polymer Derby! You may be wracking your brain trying to figure out what we are talking about here, so let me explain:

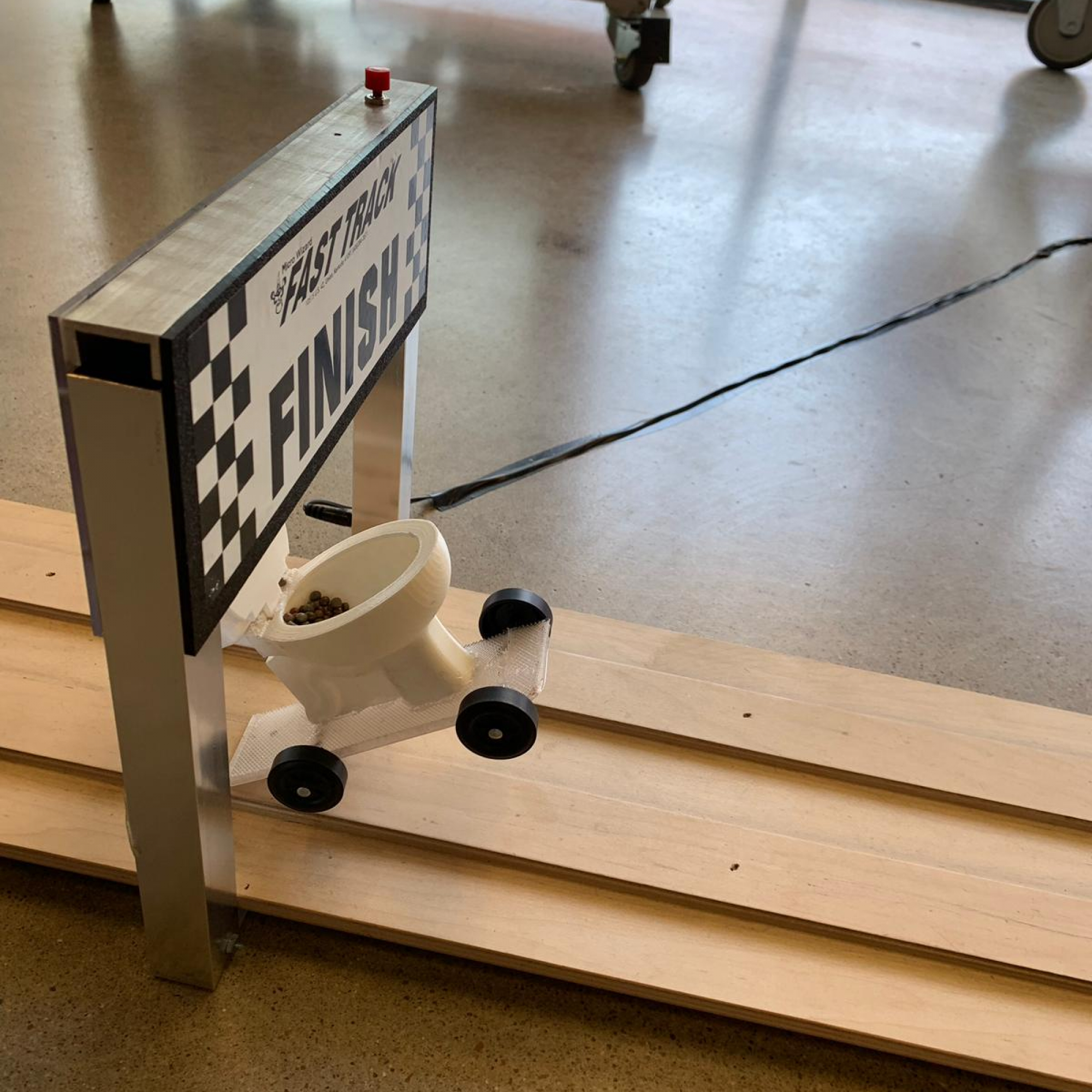

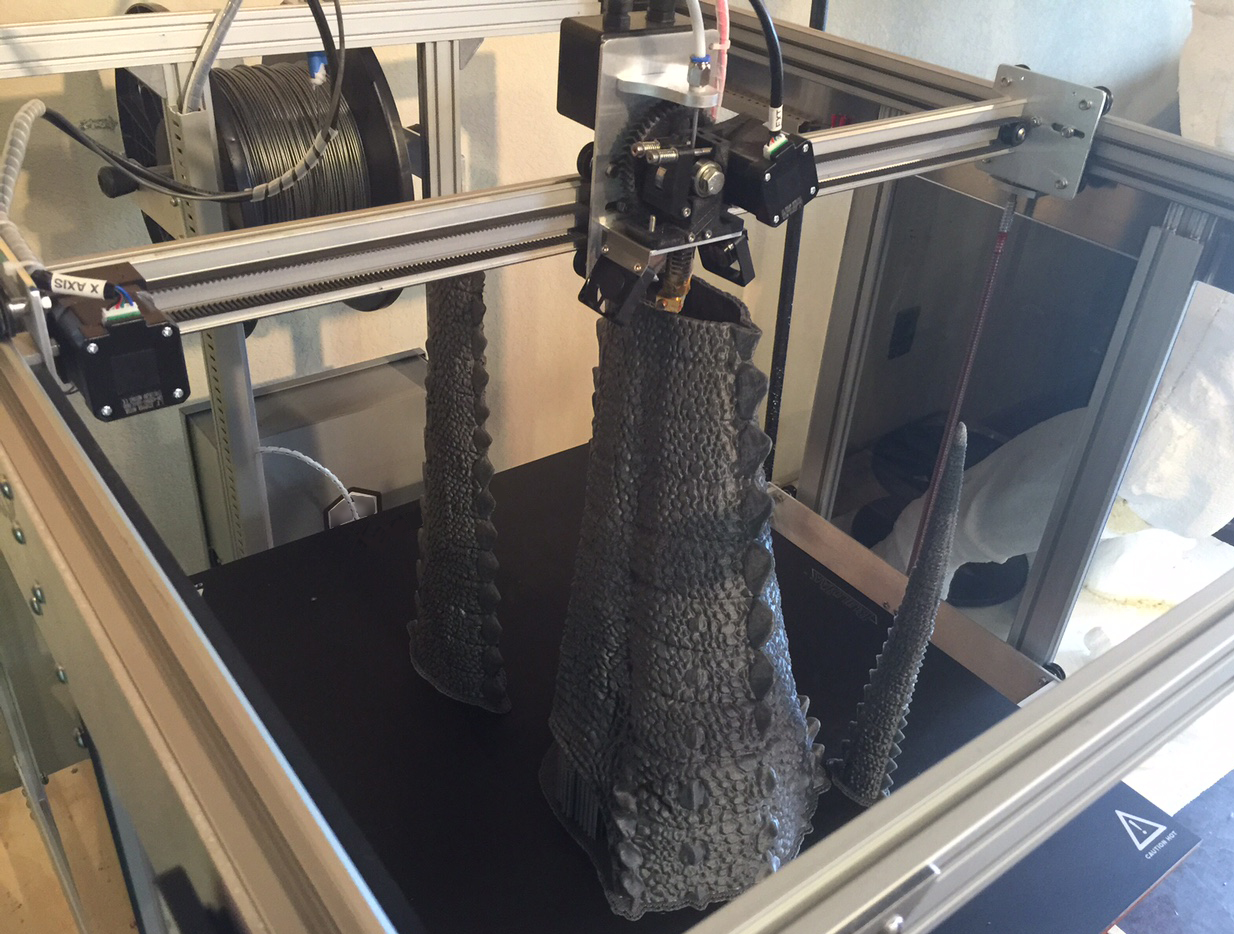

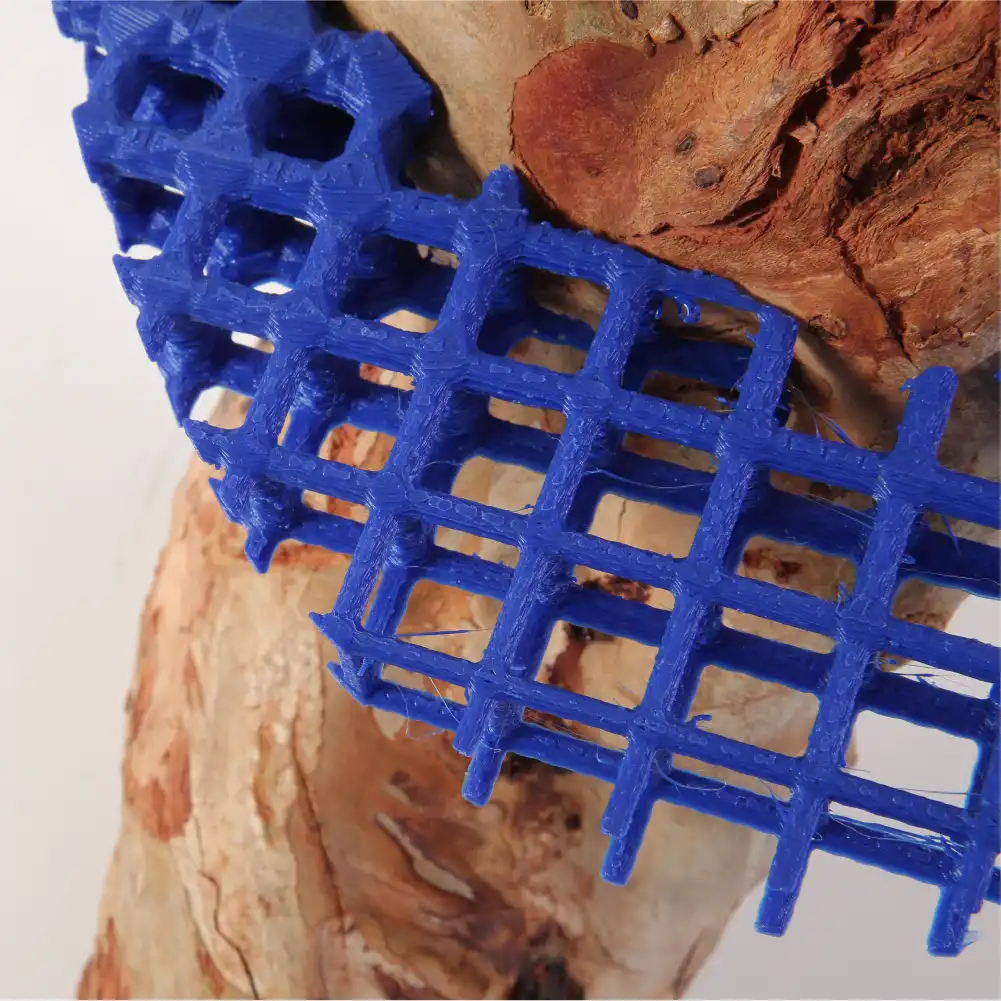

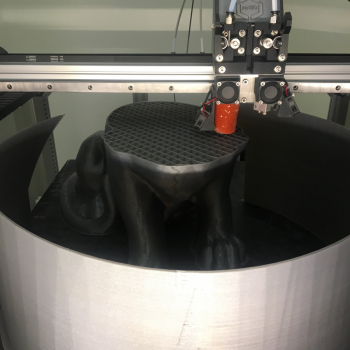

We challenged each other to a gravity car racing competition. Quite similar to a Pinewood Derby (in fact we borrowed a pinewood derby track from local Cub Scout Pack 595) – each competitor designed a car, printed it on Gigabot, attached some wheels – and we were off to the races on derby day!

As a distributed team, with competitors in Houston, Austin, Puerto Rico, and New York – we established a rule from the start that you must design your own car and if you require help with your design (since not everyone is a 3D design wizz) you had to reach out to someone in a different location from your home office.

We thought this was a great opportunity to not only get everyone designing and printing in 3D – but to also make sure that our distributed team members interacted with someone from a different office on something fun that wasn’t just work related.

Almost immediately after announcing the competition, (in mid-January) we had questions, everyone wanted to know the rules, which admittedly didn’t yet exist, and our engineers were particularly interested in finding loopholes in said rules so that they could cheat the system. I promised the team that I would write-up an entire tome of rules and got to work, we started with the basic size parameters (borrowed from the pinewood derby to fit their track), and then added layer upon layer of bureaucracy and ridiculousness on top of what should be a relatively straightforward idea (I will post rules examples at the very end of this post).

The cars had to:

- Weigh no more than 5.00 oz

- Length shall not exceed 7 in

- Width shall not exceed 2.75 in

- Car must have 5/16″ clearance underneath

- Wheels must be unmodified (we gave everyone a standard set of wheels)

Ultimately the designs were up to each individual’s creativity.

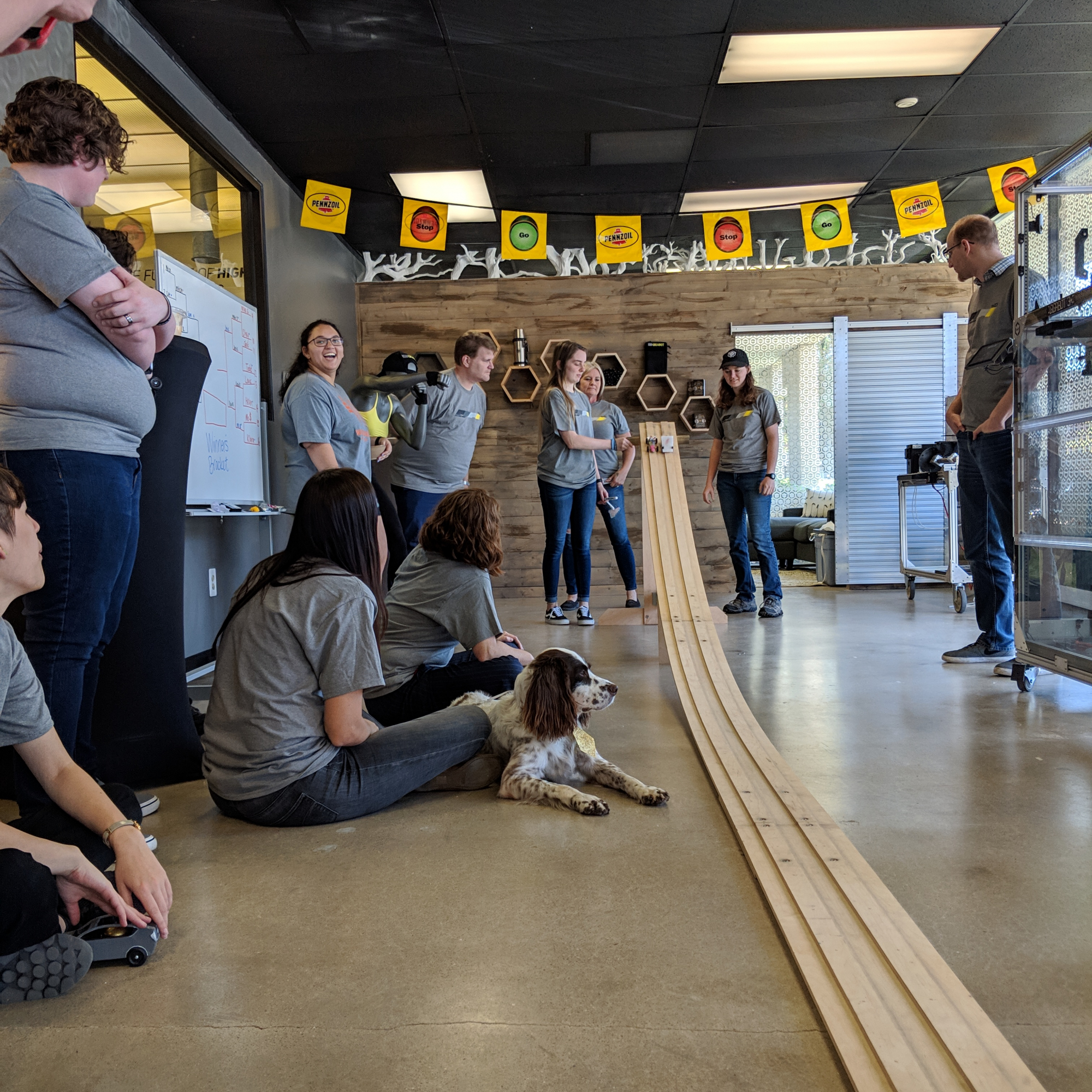

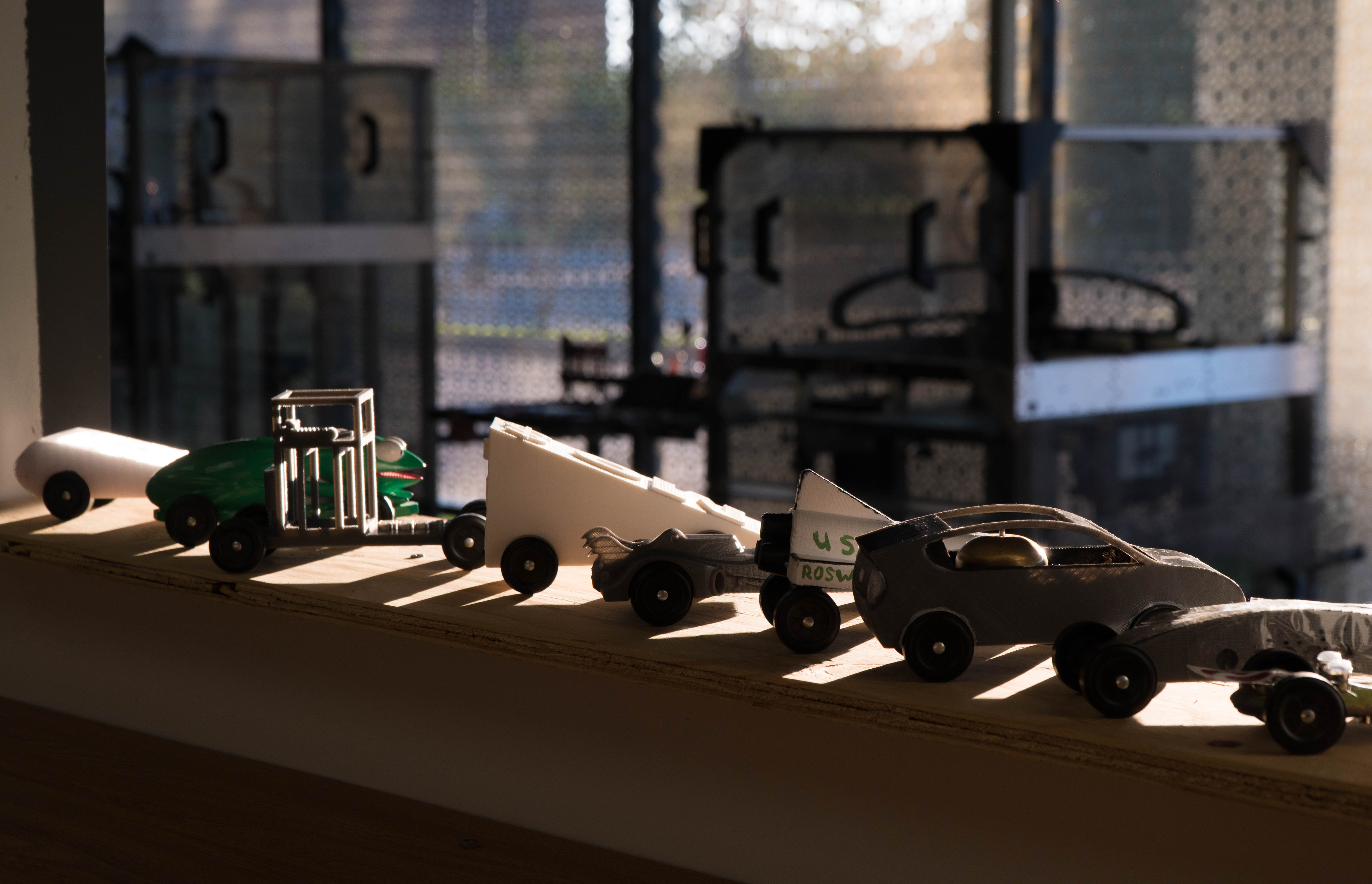

Come derby day, there was an amazing diversity in designs. The track was setup in the front showroom of our Houston HQ. We had an official weigh-in and measurement period to check that all cars conformed to the rules. We made up t-shirts to memorialize the day. And then we started the competition.

Each competitor chose a number from a hat – to get randomly assigned a place on our competition bracket. We then competed best out of 3 heats, with racers switching sides (there were only 2 racers at a time) after each heat. As the day went on, the biggest determining factor in the fastest cars was the weight. Any racer that was below 5.00 oz was at a distinct disadvantage, and all of the cars in the quarter-finals and beyond were at the target weight exactly.

When all was said and done we had a winner! Technically we had two winners – the Fastest Car – won the racing piece of the competition. The Flyest Ride – was voted as the best looking car by all of the competitors. Congratulations to Samantha (fastest car) and Mitch (flyest ride).

Stay tuned for more Polymer Derby fun, as this will definitely become an annual event at re:3D, and perhaps across the world?! Sign-up for our newsletter to always be up-to-date on what’s happening at re:3D.

Looking forward to next year's competition!

International Polymer Derby Congress Rules & Regulations (These are just a small sampling of the rules for this competition):

- Cars shall be 3D printed – in any material that is currently able to be 3D printed.

- The majority of the car shall be printed on an FFF/FDM style 3D printer, but does not have to be printed in one piece.

- The car must be free-wheeling, with no starting or propulsion devices

Inspections:

The day of the race, while style voting and race seeding is taking place, race officials will open the Inspection Zone:

- Cars will be Inspected individually for conformity to all rules of the IPDC and the Polymer Derby Championship Racing Series (PDCRS).

- Each car will be weighed (see weight requirements Sec. 1.2 A-I. above)

- Each car will be measured for length, width, ground clearance, and wheel clearance (Sec. 1.2B – I-IV).

- Each car will be thoroughly inspected for any potential safety or hazard violations

- Each car’s wheels will be gone over with a fine tooth comb, as modification of stock wheels is strictly prohibited (In accordance with Sec. 1.2 C – I & II)

- Any car found to have illegal modifications to the wheels is subject to being gleefully smashed with a hammer by a race official (viewer discretion is advised)

Failed Inspections:

- Any competitor’s car that is found to not pass inspection will have an opportunity to adjust/fix their vehicle and have it re-inspected. An explanation of why the car failed inspection will be given to each competitor and the racer will have 10 minutes to make the proper adjustments to bring their vehicle into conformity with the race rules.

- If the racer fails to bring their car into conformity within 10 minutes, fails to present their car for re-inspection before the 10 minute time period is up, OR fails the inspection for a second time – the car is no longer eligible for the Fastest or Flyest awards (Sec. 8 Subsec I-III.), but is eligible for the Junker award (Sec. 8 Subsec. IV.).

- Cars that fail the secondary inspection may still participate in the tournament for fun, but will not be eligible to win.

- If you make illegal modifications that go undetected by the judges, but manage to make your first run before judges take notice, you may continue using your illegal car without reprimand. Gamble at your own risk.

Style Voting:

While the fastest car down the track is the ultimate winner – there will be style points given out for the car that looks the best.

- Subjective voting will take place by each competitor at the beginning of the competition.

- The voters/competitors may use any method of determining the best “looking” car that they see fit.

- Each competitor will fill out a secret ballot to determine their favorite car.

- Each competitor will vote only once and can not vote for themselves

- Bribes for style votes, while not illegal, are harshly discouraged.

Grievances:

Official grievances may be filed.

- For a grievance about a particular heat/race the grievance will only be valid if:

- Filed within 180 seconds of the race ending, in written form, adhering to the following parameters:

- Printed, in landscape orientation, on standard sized paper (8.5”x11”)

- Comic sans font

- font size = 17.5pt.

- The grievance must follow the standard limerick format

- Five lines – 2 long, 2 short, 1 long,

- Rhyme scheme AABBA

- Sent via USPS standard mail, postage paid to:

- Filed within 180 seconds of the race ending, in written form, adhering to the following parameters:

International Polymer Derby Congress

Department of Rules, Grievances, and Dispute Resolution

re:3D, Inc

1100 Hercules Ave, Suite 220

Houston, TX 77058

Or hand delivered, with a bow/curtsey, directly to the Rules Czarina or Czarina designate for an immediate ruling

Awards:

- Fastest: Fastest car to win the final race, wins the Polymer Derby Champion Award

- Flyest: Top vote getting car for style wins the “Best-in-Show” – Flyest Car award

- Little Miss Fly-Ride Should the top style car and top speed car be one in the same – the title of “Champion of Champions” or “Little Miss Fly-Ride” will be bestowed upon the winner along with lavish praise and an award of at least one but not to exceed 100 cheap beers.

- Junker: The “Junker” award goes to any car that fails to make it down the track, or breaks at any point during the competition. It is quite embarrassing.

- Flunker: The “Flunker” award goes to any car that fails the pre-race inspection, and is not eligible to win awards I-III of this section.

Mike Strong

Blog Post Author