Chuck Grant wasn’t with the Magnolia Fire Department in 2011 when the Riley Road Fire happened, but the effects of the massive blaze on the department he now works for as Assistant Fire Chief and Chief of Technology are still visible.

The fire took 10 days to contain and burned nearly 19,000 acres in Magnolia, Texas, northeast of Houston.

“The fire was in such a size that it knocked out cell service in a lot of areas,” Chuck recalls. This meant that the department’s typical public alert methods using Facebook, Twitter, and other cellular-dependent mediums were off the table. They had no easy way to communicate with the community they were trying to help.

What the firefighters found is that when residents didn’t know where to go or what to do, they came directly to the fire station to try to get information. But in a large-scale disaster like this one, that was a problem. “There was no one in the fire stations because they were all dealing with the emergency,” Chuck explains. The fire exposed a serious communication problem they realized they needed to remedy.

When Chuck joined the team, he began working with the Fire Chief to devise a solution to this problem.

What they came up with was something akin to a tool that many businesses use for public messaging: LED signs. The signs would be out front of each of Magnolia’s nine fire stations to display updates and actions during large emergency events, with the ability to change the information quickly and from the field.

The next order of business was aesthetic – they wanted to add a symbol of the fire service to the signs to make them their own, something that would look good for the community.

When they settled on the idea of a large fire hydrant statue on either side of each station’s sign – two at each location meant 18 in total – the next challenge became how to get them made. They started investigating options like fiberglass and bronze casting, but quickly realized that everything was far out of their budget.

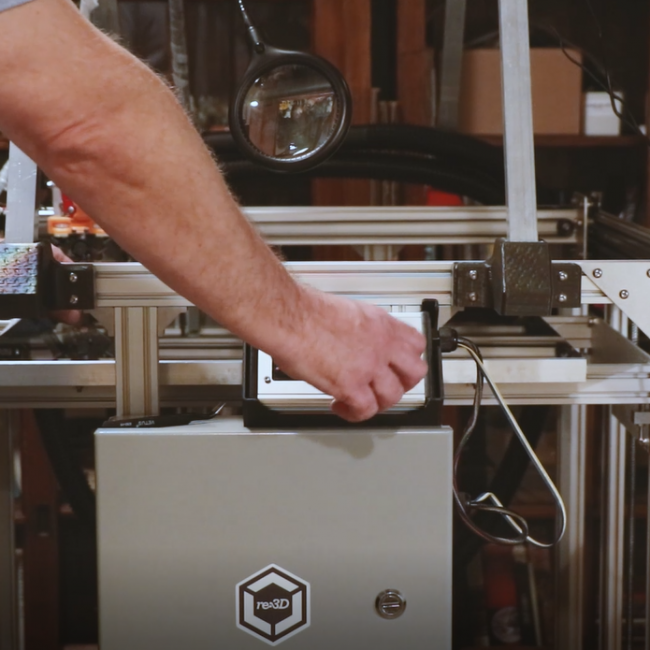

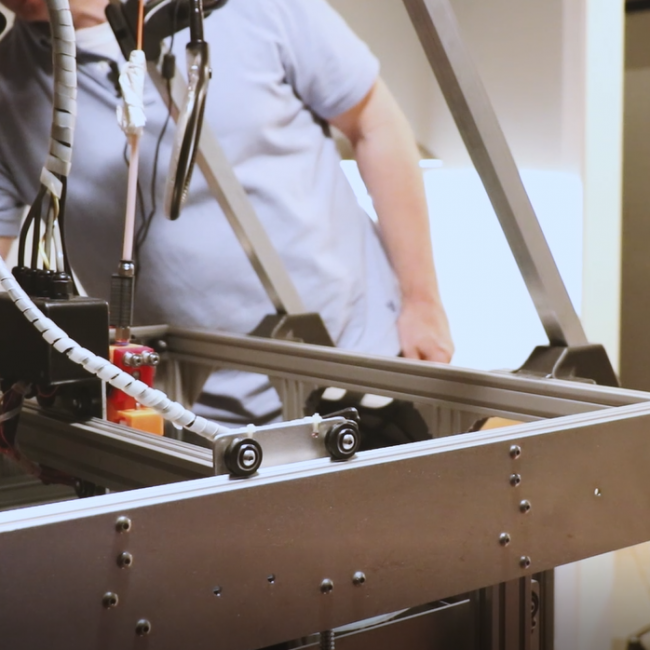

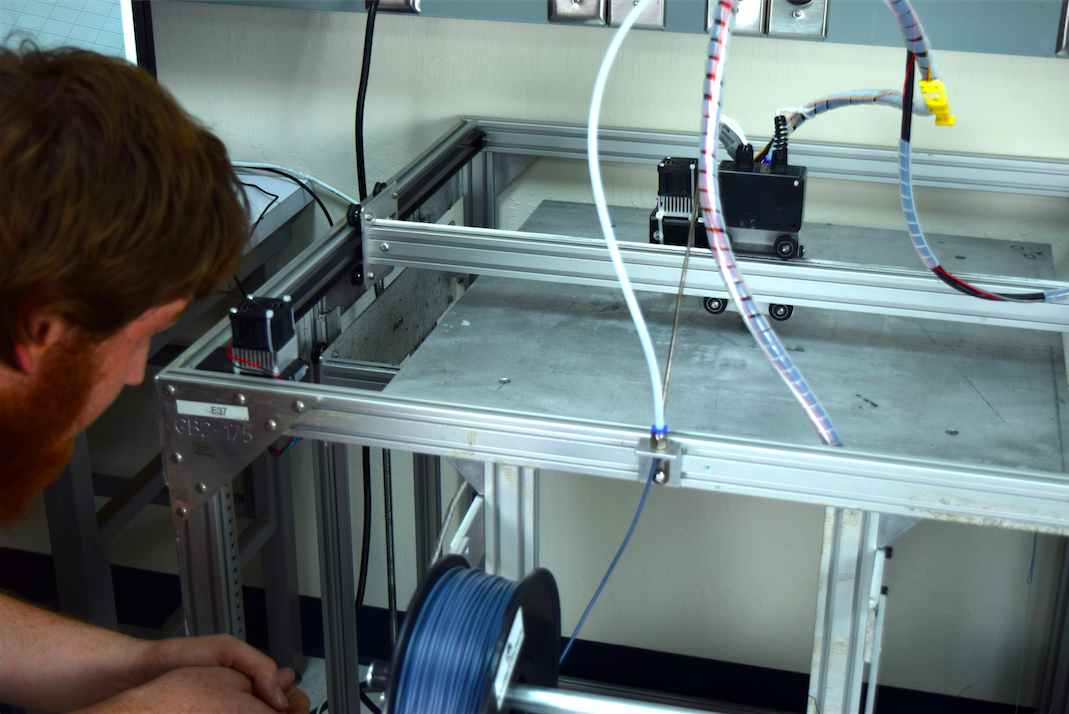

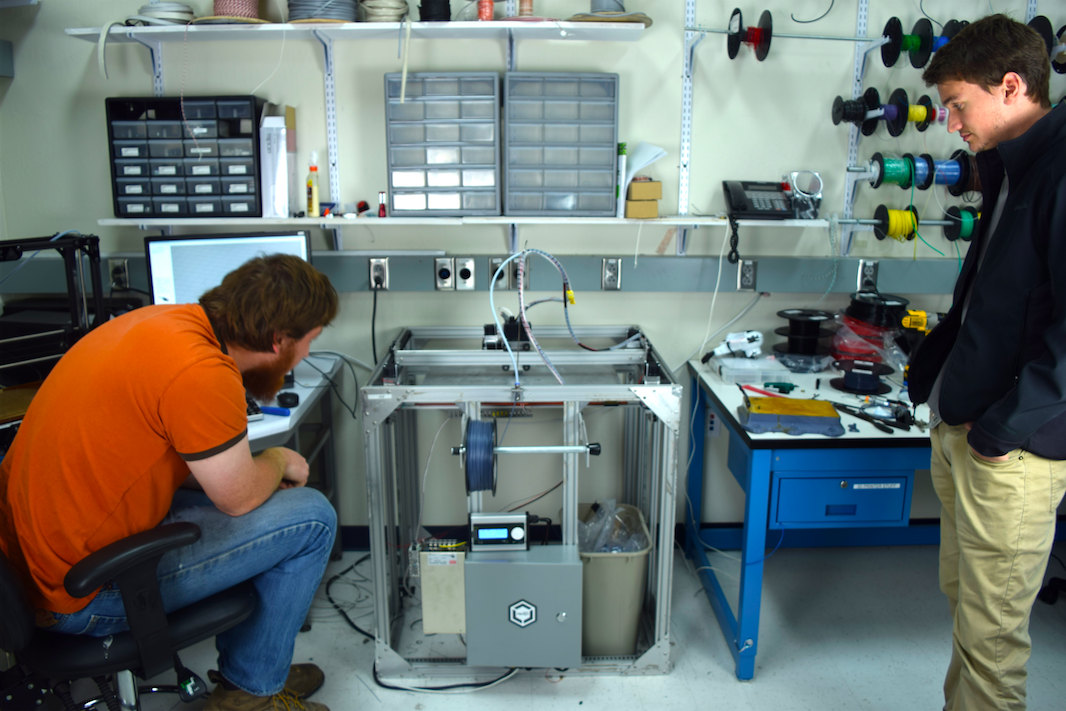

That’s when they found Gigabot.

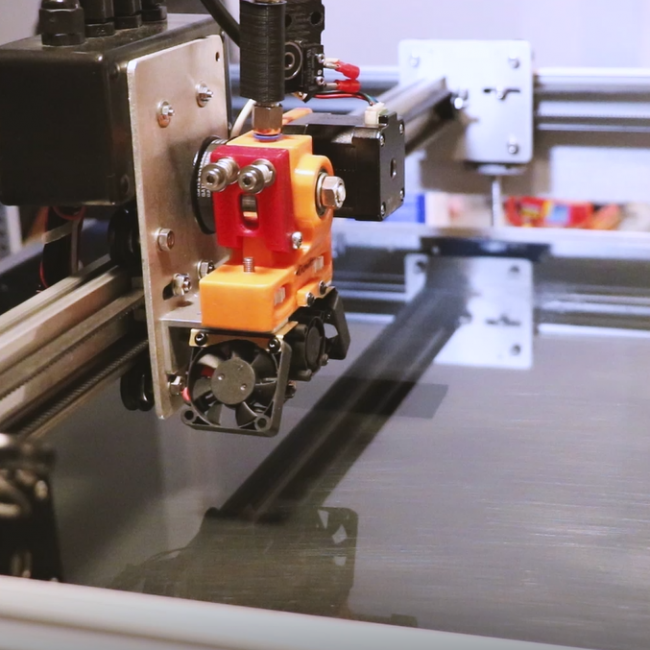

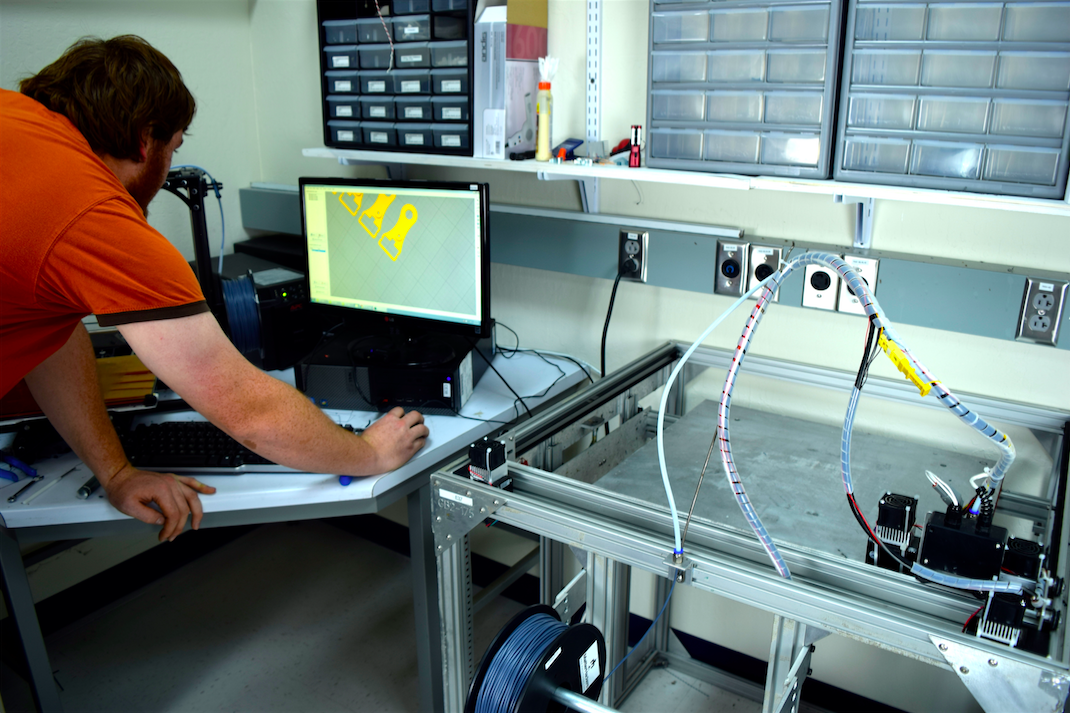

The sign project in conjunction with other potential uses for 3D printing at the station made getting their own Gigabot and fabricating the decorative hydrants themselves the most cost-effective option. Chuck already had a background in 3D modeling, so designing the hydrants was no problem. “It was just a matter of scaling something up from, say, an inch tall to 99 inches,” he said. “And the Gigabot was able to do that for us.”

The build volume of Gigabot was the original draw for their sign project, but in order to make the purchase financially worthwhile to them, they wanted the bot to have a second, longer-term use. This is where the RFID tags enter the story.

Fire stations operate under a system of strict regulations: a truck must have a certain amount of equipment before it can respond to emergencies, and this equipment has a variety of imposed lifetimes that need to be tracked. Chuck explains, “When I started 35 years ago in the fire service, no ax had an expiration date on it – either it worked or it didn’t. And now that’s all kind of changed. So the need for technology has really, really ramped up.”

On top of this, equipment must cycle in and out of the repair room as it’s damaged. A tiny crack to a mask takes that mask out of service until it’s fixed. Keeping track of what equipment is damaged, what needs to be replaced on trucks, where damaged equipment is in the repair process – they’re all more processes that need to be tracked.

All of these components add up to quite the logistical headache for fire stations: monitor the ticking clocks on your equipment to make sure active tools are not outside their expiration dates and take things out of circulation when they are, keep track of damaged items in for repair, and ensure your trucks have all the equipment they need to be ready to respond to a call at a moment’s notice.

It’s quite the operational feat for organizations whose main function is to save lives and battle fires.

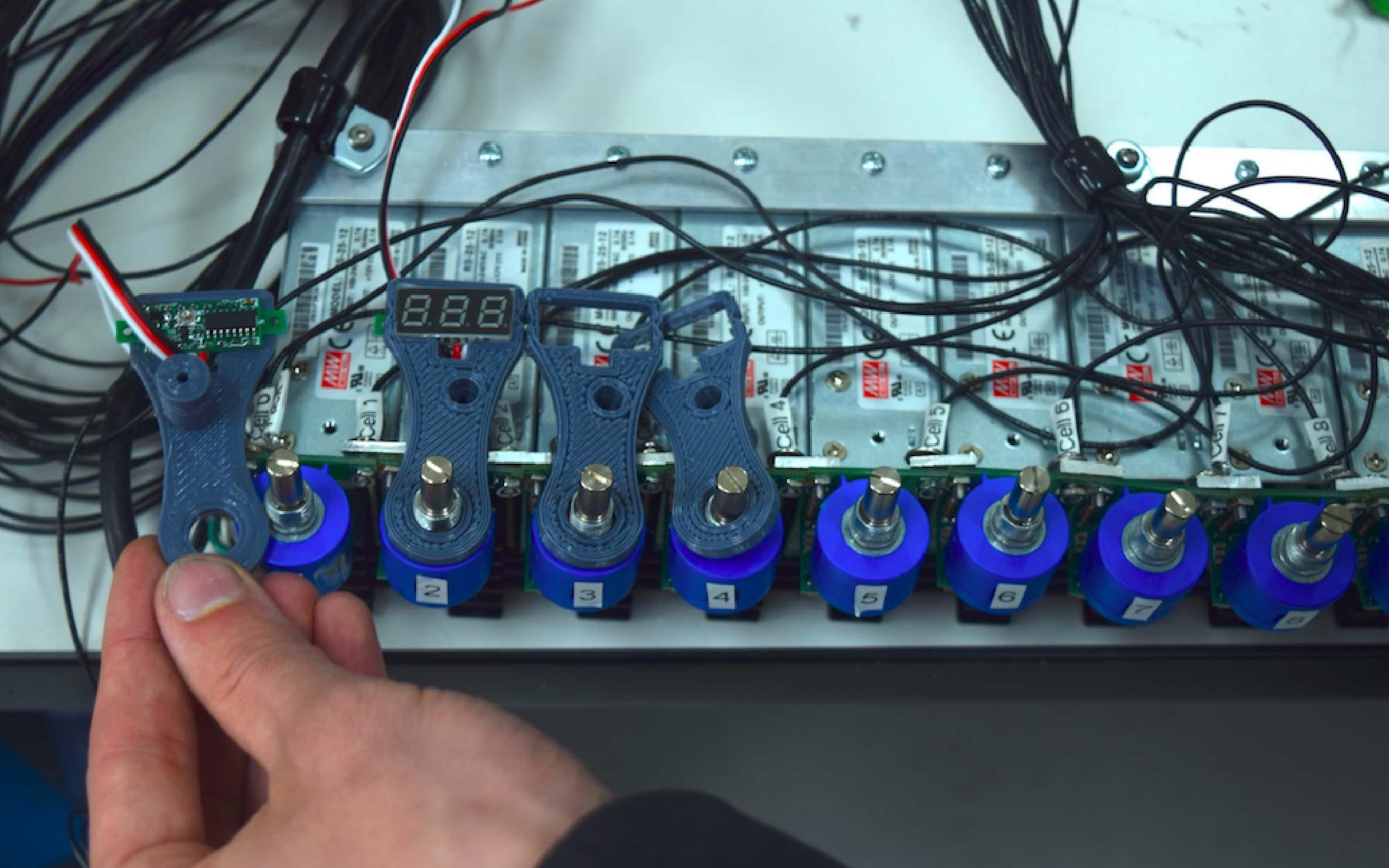

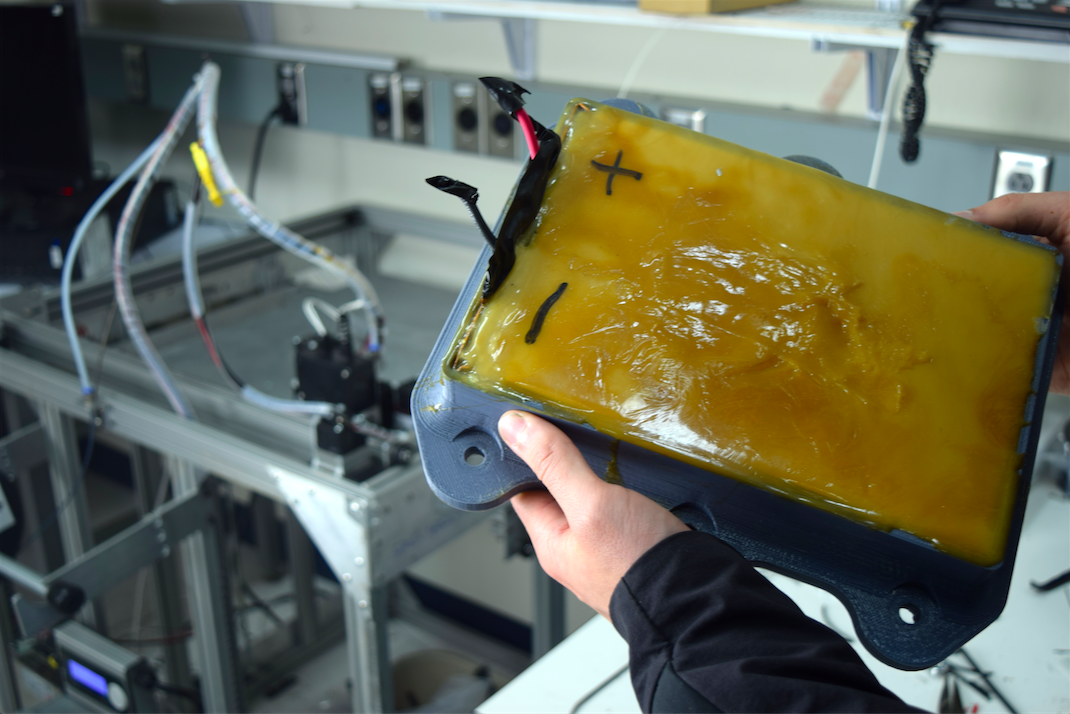

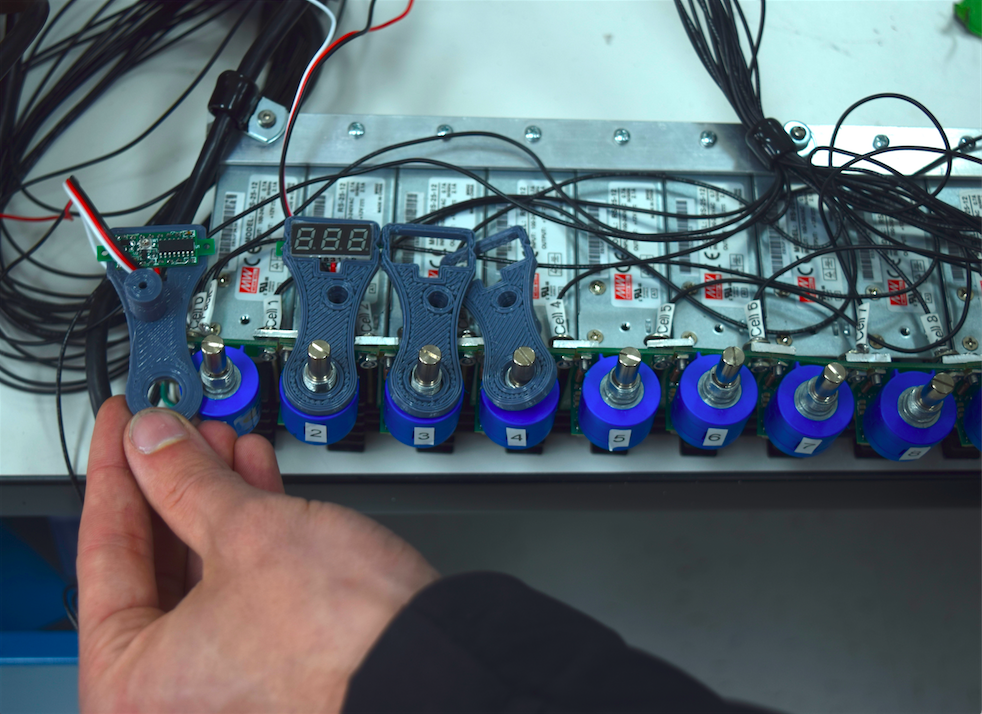

In the interest of allowing firefighters to do what they do best, stations are looking for ways to manage all their equipment tracking in the most efficient way possible. Magnolia Fire found a solution in RFID tags from Silent Partner Technologies. The small radio frequency identification devices have an adhesive on one side to affix them to objects and they can be scanned from a distance and tracked via software on a computer. Chuck explains, “It very quickly gives the firefighters the chance to scan the truck and know that the vehicle is ready for them to respond to a call the minute they come into work.”

The problem was, Magnolia quickly realized that the harsh firefighting environment in conjunction with the wide variety of materials they had to tag was proving to be too much for the adhesive tags. “Because the fire service is a tough place to be a little tag, the adhesive strips on the back don’t hold up as well as they would in another application,” he explained. Heat from fires, water from hoses, and the general physical battery that the firefighting tools endure took their toll, and the department found themselves returning from events sans many of their RFID tags.

A solution, they realized, lay in 3D printing.

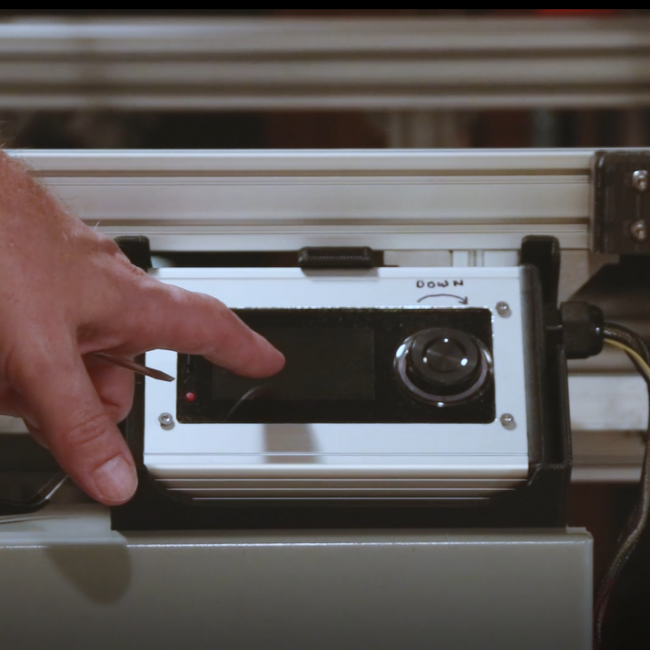

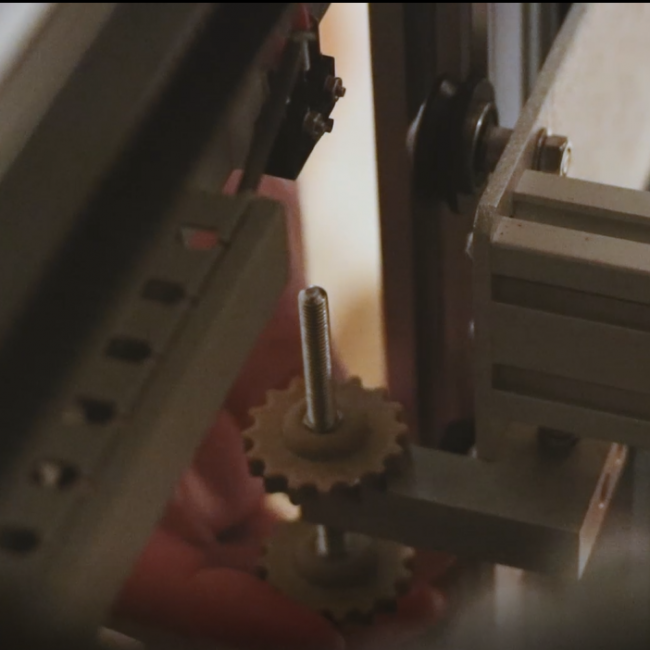

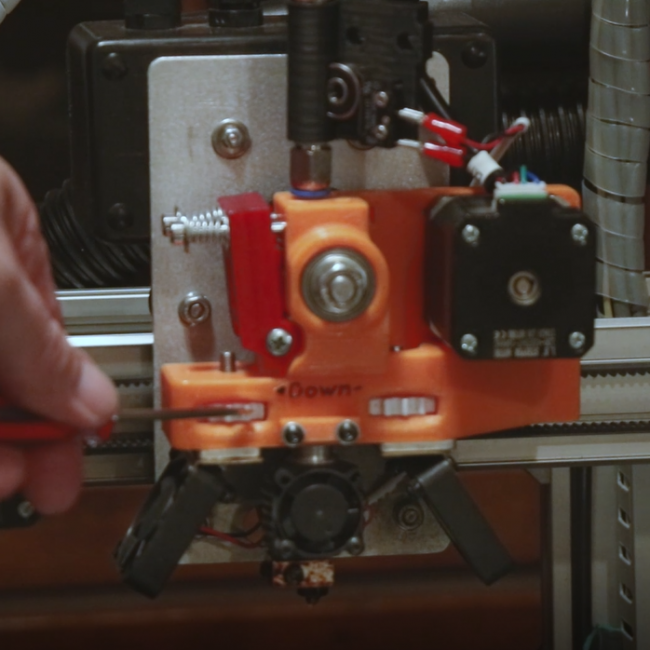

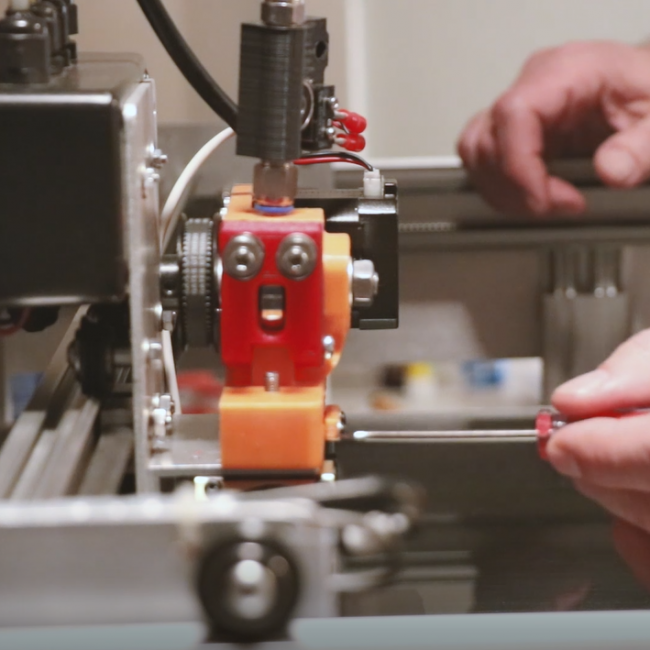

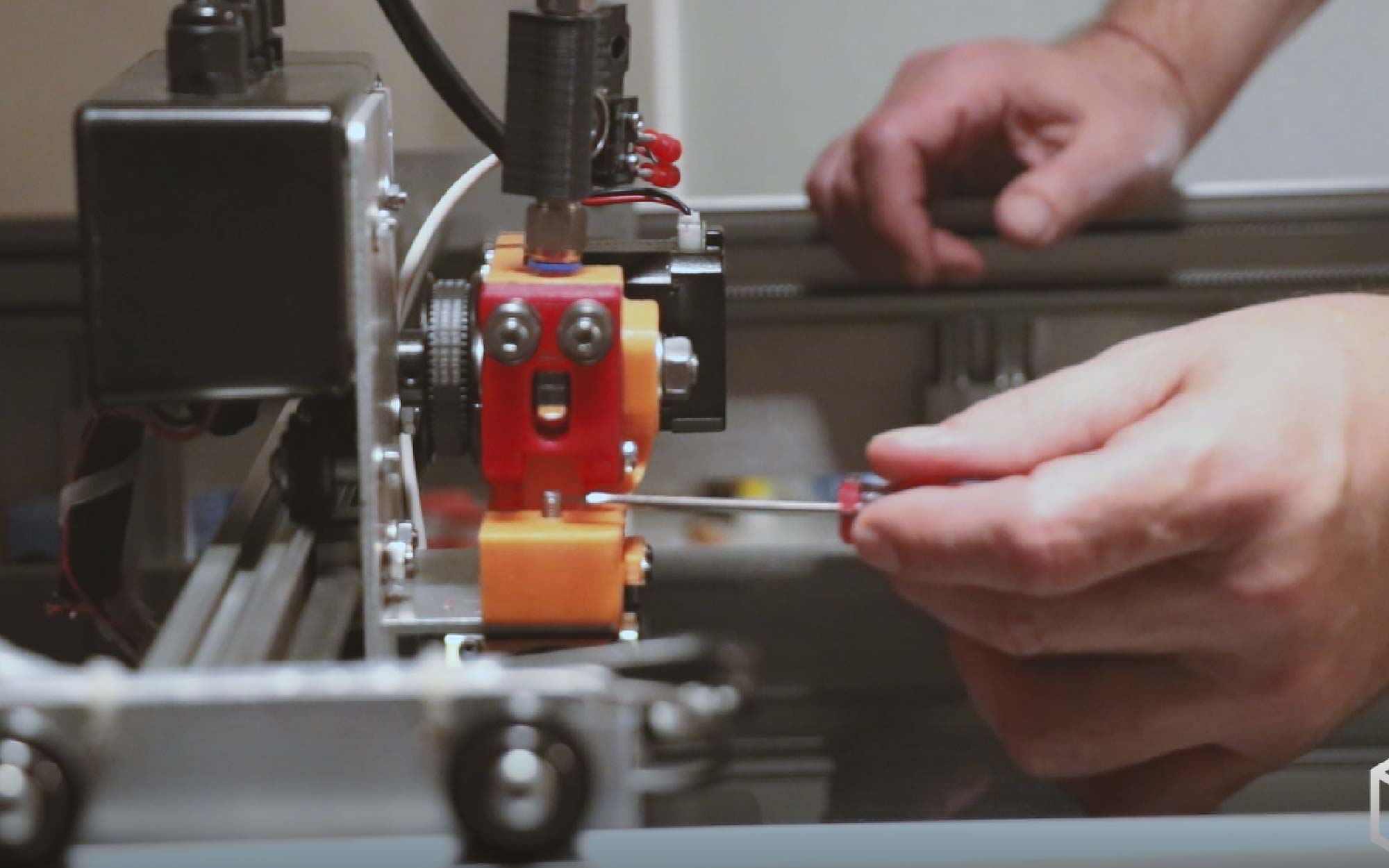

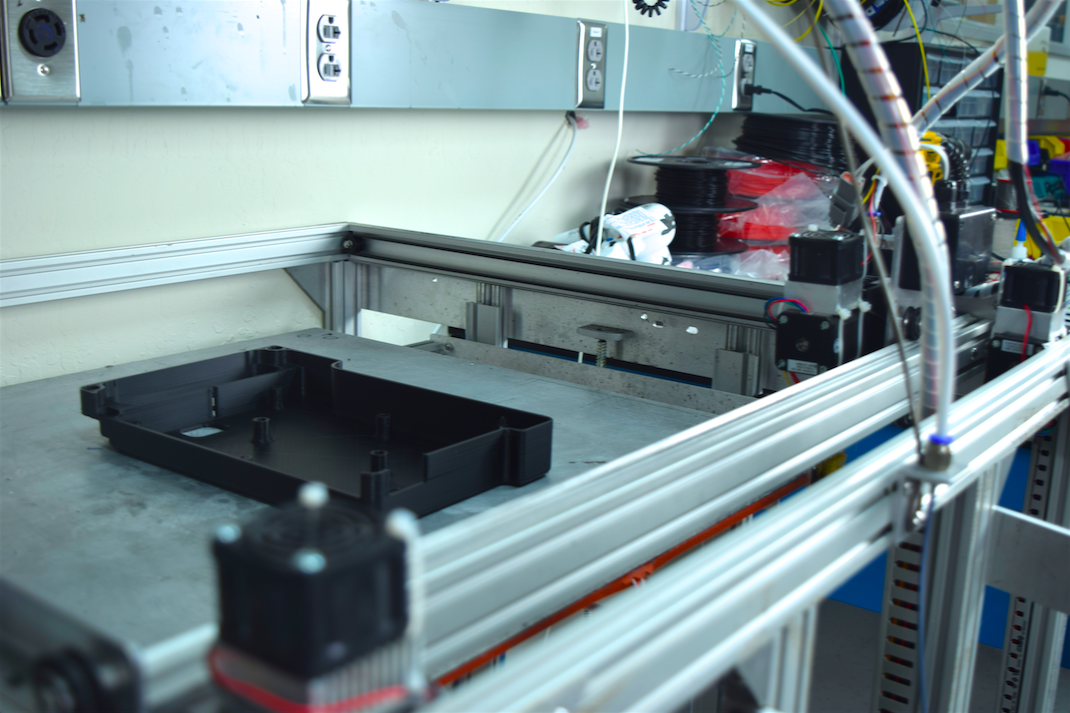

Using Gigabot, Chuck has been printing small compartments for the RFID tags to fit into which they can then mechanically fasten to their tools. 3D printing the tag holders provides a uniform material to which the adhesive can adhere, while also tucking the tags away where they can’t get bumped off. And they can do this all without altering the form and function of their well-designed equipment.

“All of our items have been well-designed, they’re well-engineered, and so for us to just take something and stick it on the side of it isn’t really a great option,” Chuck explains. What they’re doing is replicating a certain component of an object and building a pocket into it where they can hide a tag. The clip of a flashlight, for example, is replaced with its 3D printed clone, plus one RFID tag that you wouldn’t know is there. This becomes infinitely important when when you’re in a smokey room with thick gloves on, where a foreign part on a familiar tool can lead to dangerous confusion.

If the sign project was what led Magnolia Fire Department to Gigabot in the first place, creating custom RFID tag holders for their equipment is what kept them coming back. It’s proven to be the long-term justification they wanted in order to get their own 3D printer on-site.

“We certainly had this sign project that’s important…it’s going to be the thing that people notice the most because it’s going to be out in front of the building,” Chuck says. “But long-term, to get the most out of our investment, we need that secondary…task for the Gigabot to do.” The ongoing RFID project checks that box.

Gigabot has also proven itself as a problem-solver for issues that weren’t necessarily originally on Magnolia’s 3D printing radar, as the department now has the ability to produce any sort of custom-made pieces they desire. “Instead of going into the marketplace and kind of having to mold to what is available, we can meet our own needs by drawing our own parts and printing them,” Chuck explains.

An example of one such piece is an ingenious yet simple part to hang the firefighters’ masks inside the trucks, keeping them off the seats and floor where they’re more likely to get damaged, and hanging them in a way that doesn’t put stress on the facepieces. The clever design fits into the masks where the firefighters’ air tanks connect; with one twist they lock onto the piece so they can’t fly off en route.

The station’s service room is lined with equipment in for repair, including a table full of dinged masks. Much of the damage was due to them being tossed around inside trucks or hung in a way that puts undue stress on the temples of the masks, causing them to crack over time. This new piece, they explain, solves these problems and was infinitely simple for them to manufacture.

Clessie Hazelwood, Battalion Chief at Magnolia Fire Department, originally saw the design 20 years ago at a different fire department. Chuck prodded him to talk about how much effort that department had to go through to produce one. Clessie sighed, “Oh…they had to do machining, set up dies and everything.” It was a long, costly process.

When Magnolia got their Gigabot, Clessie came to Chuck to see if the part was something he could print for them. Chuck chimed back in, “From the time you told me about it ’til the time you held it in your hand, how long did it take?” Clessie paused.

“Less than a week.”

Morgan Hamel

Blog Post Author