As you may have seen, we launched a global 3D printing furniture contest this summer in pursuit of finding a 3D printed solution to quickly assemble furniture in preparation for this year’s hurricane season. Called the “Fast Furniture Challenge”, we opened up this problem to our global community in exchange for a $250 cash prize.

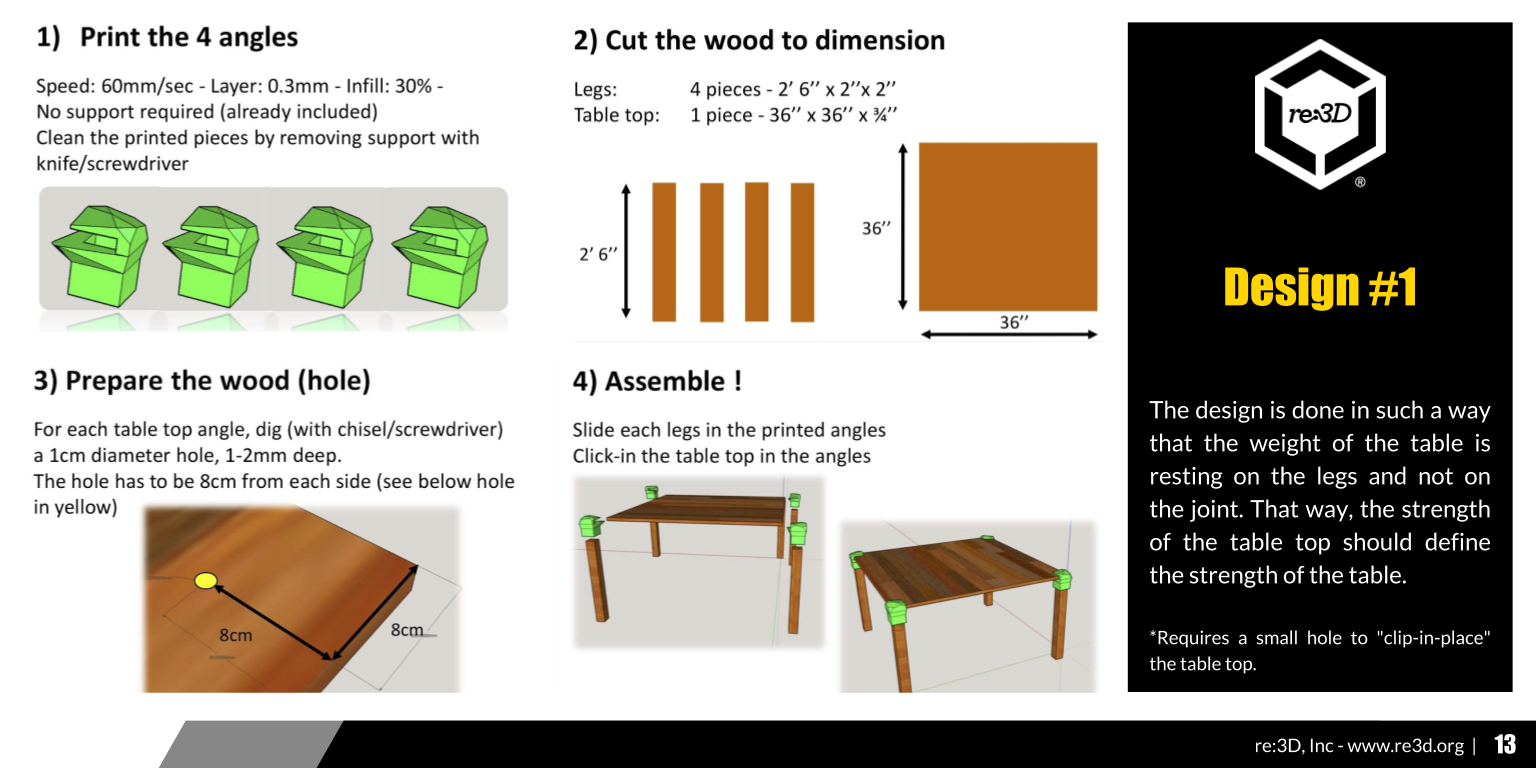

Applicants were judged on a set of criteria including print time, cost, materials restrictions, weight load, and ease of assembly. Winning prints had a print time of under 48 hours, cost less than $20 to print, and were easy to assemble and disassemble using only pre-cut wood from Home Depot for the final piece of furniture to hold at least 150 pounds.

Participants submitted .STL files and digital presentation boards and our team judged the designs based on each design’s creativity, presentation board, .STL quality, estimated print time and ability to print without supports. The top designs were then printed and put to the test – the final product was judged on the ability to withstand 150 pounds, how easy it was to assemble and the cost of the print.

We’re excited to announce our winner…drumroll, please…Sylvain Fages! Sylvain’s design printed a set of joints (4 joints = 1 table) in 12.08 hours, using 1.07 lbs of PLA for a $20.21 material cost. The prints had 15% rectilinear infill and no supports were needed. Also, shout out to the runner-up: Daniel Alvarado from ORION.

Below you’ll see some snapshots and assembly footage from Sylvain’s winning design and the final product our teammate Alessandra put to the test.

Reviewing Design Boards & .STL files

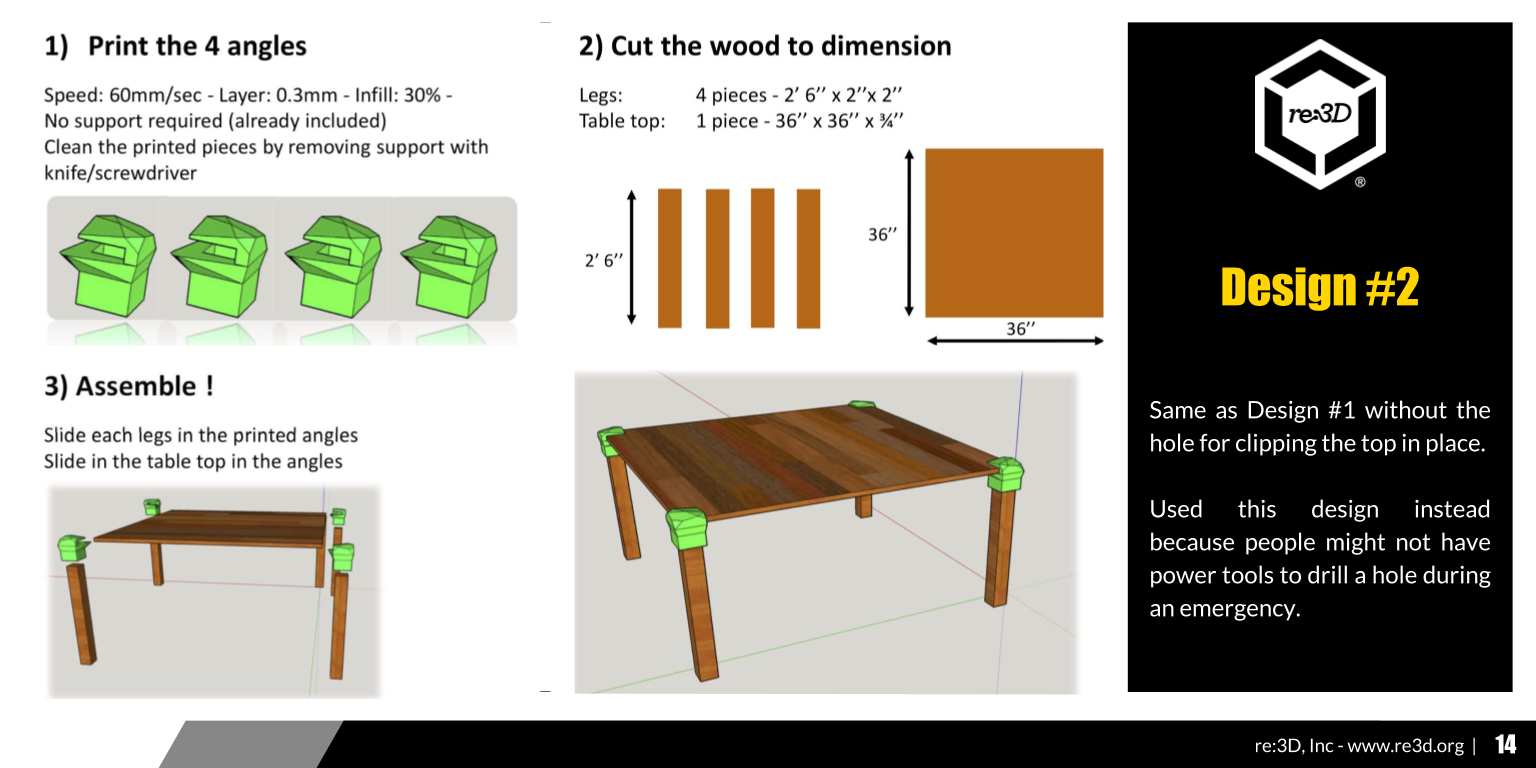

Sylvain submitted two design presentation boards (you can also access the original Sylvain Designs PDF).

Design #1 was done in such a way that the weight of the table is resting on the legs and not on the joint. That way, the strength of the table top should define the strength of the table; however, requires a small hole to “clip-in-place” the table top.

Design #2 is almost the same as design #1 but without the hole for clipping the top in place. Design #2 was selected for printing as it does not require access to power tools that may not be available to people during emergencies.

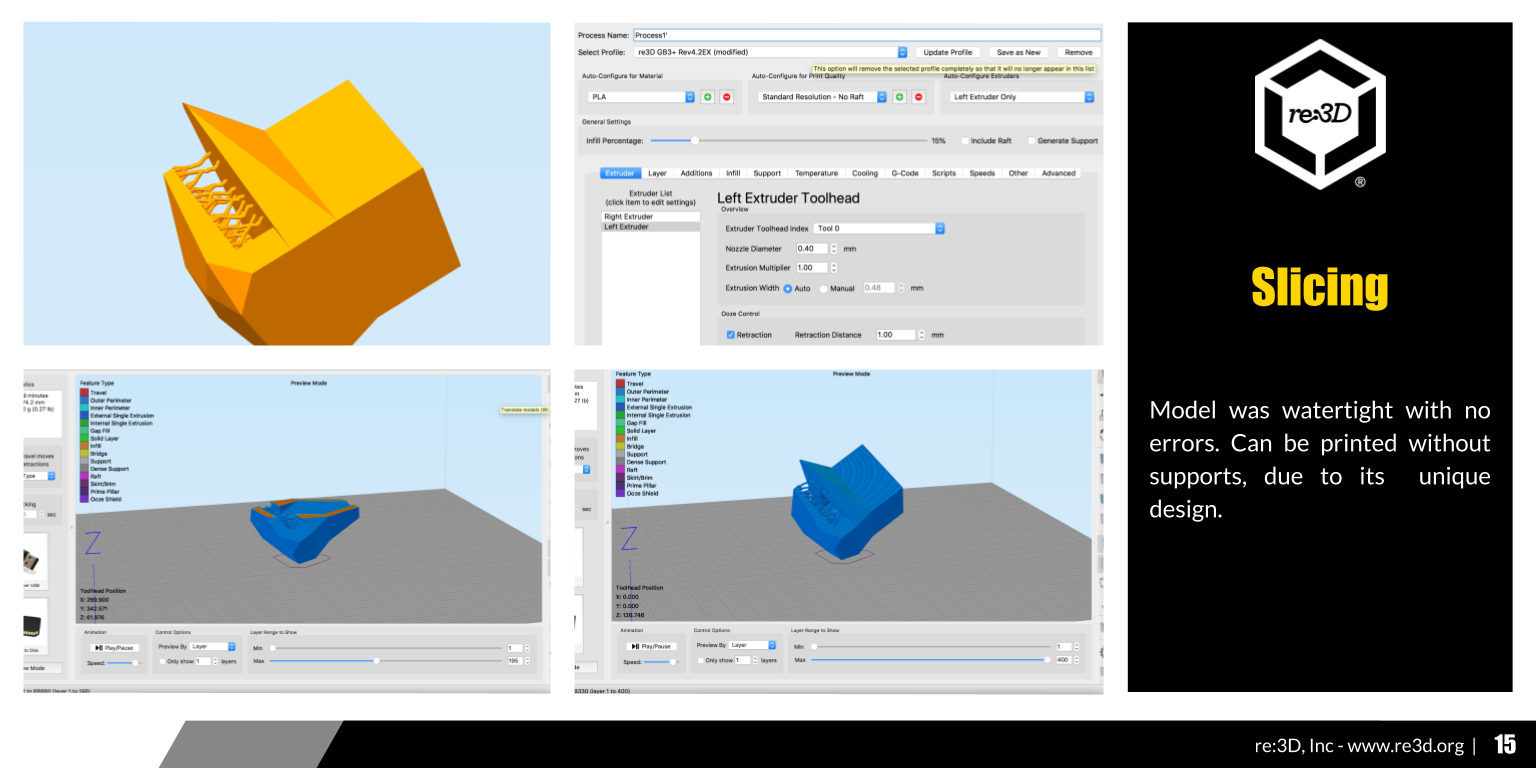

.STL file review & slicing revealed the model was watertight with no errors and can be printed without supports, due to its unique design.

Testing the Joints

After selecting the top designs, we put them to the test by 3D printing them and assembling tables using pre-cut wood from Home Depot to evaluate ease of assembly, their stability and ability to hold up to 150 pounds. Here’s footage from Sylvain’s printed designs:

3D Printed Table Joints Assembly Video: Ease of assembly was an important factor in choosing the winner, watch Alessandra assemble a table w/ Sylvain’s 3D printed furniture joints

Weight Test Video: We also tested that the table could hold up to 150 lbs.

Table Stability Video: Alessandra tested the level of the table’s stability.

Final Product Photos

Here are some snapshots of the joints in action after the table was assembled. Click to view bigger photos.

Lessons + Insights

As you may have seen in our first post announcing this challenge, this Fast Furniture challenge was inspired by personal experiences our team endured during Hurricane Irma and Maria which we will continue to be sharing in our 3D printing recovery series. We ourselves went through rounds of trial and error to find a 3D printed solution to assemble furniture quickly – which was one of the biggest requests in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. I caught up with our teammate Alessandra who shared some lessons from our experience and learnings from this challenge. Here are her key takeaways:

- Joints with 3/8″ wall thickness are very resistant to breaking. Previously, we were using 1/8″-1/4″ wall thickness for joints and they weren’t as strong as Sylvain’s. That extra 1/8″ does the trick!

- The configuration of the joints allows the table top to rest on the wooden legs and not the 3D printed furniture joints, which greatly reduces its probability of breaking.

- No matter how thick the 3D printed part is, braces are needed for full stability.

We asked Sylvain his motivation for 3D printing and entering this challenge, he shared, “Since I discovered 3D printing through a blog article about fixing a stroller back in 2014, I have always been fascinated by how much you can do and build! I bought (and built) my first printer in 2015 and have since then always admire the possibilities you have with of 3D printing, especially to fix, recycle, and reuse things. When I heard about this challenge, I could not resist but to participate! Using 3D printers to improve our world and help people – this is my vision of a 3D printer at its best!” You can view more from Sylvain on Instagram and Thingiverse.

If you have more questions, you can tune in to more discussion on 3D printing fast furniture on our forum and stay tuned for future 3D printing contests by following us on social media @re3Dprinting on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and sign up for our monthly newsletter for the latest updates and opportunities. What’s a global challenge you want to solve using 3D printing?

Cat George

Blog Post Author