“You’re always going to have the people who are going to say, ‘Oh, what are you gonna do with a fine arts degree?’”

Lauren Haug is a third-year student at Monmouth University pursuing her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Design, and she’s all-too familiar with the reactions that come with being a student interested in following a passion for art into higher education.

“But when it comes to doing this interdisciplinary stuff, you get to open up so many more avenues that you never thought you’d be able to go into.”

It was at Monmouth that she fell under the tutelage of Kimberly Callas, an Assistant Professor teaching drawing, sculpture, and 3D design at the university, and that Haug’s career visions underwent a stark trajectory change.

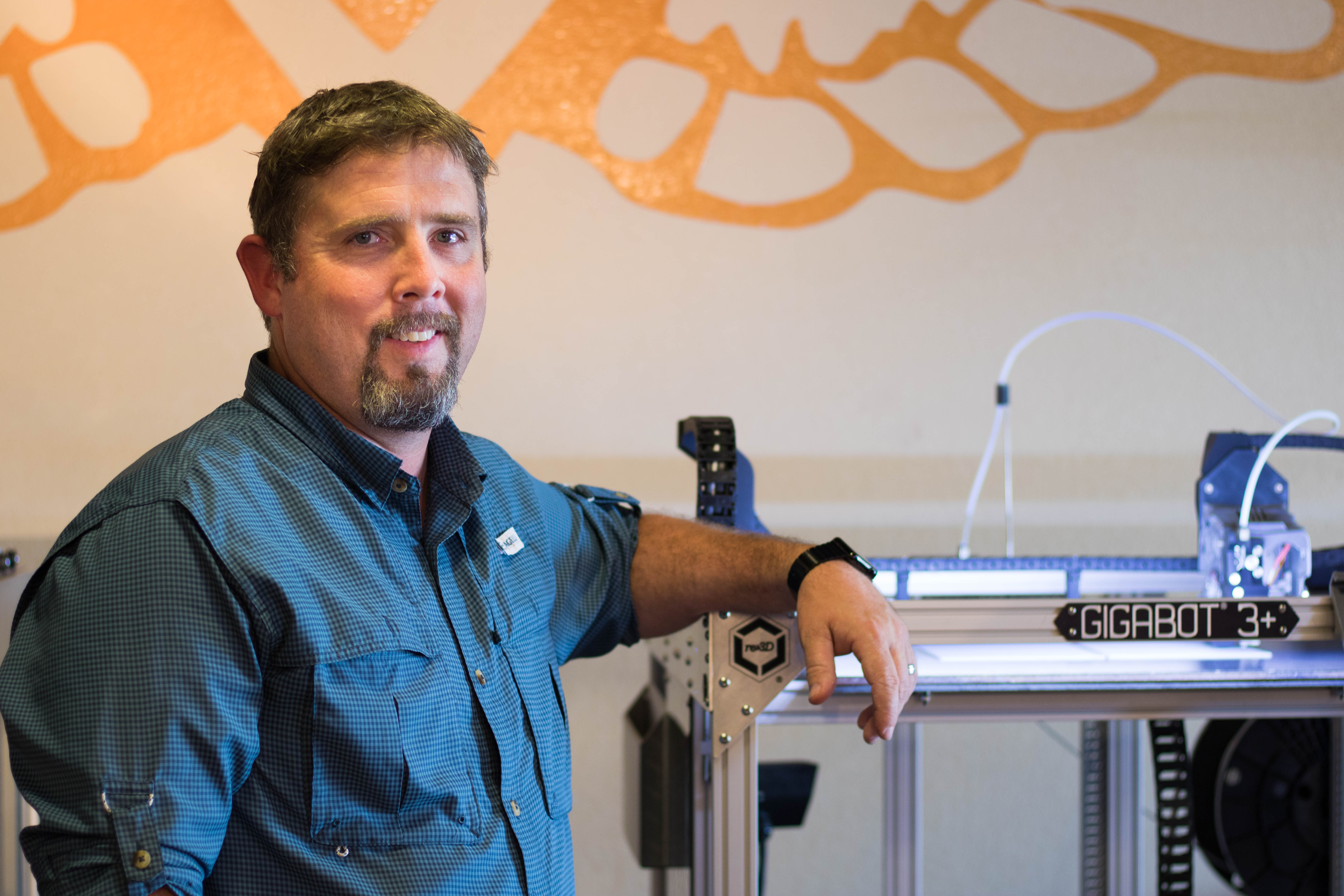

Callas is an academically-trained figurative sculptor and social practice artist. Her craft is a very old tradition – she sculpts in clay and casts her work in bronze or concrete. And yet she’s been on the forefront of adopting new technology and finding ways to use it to better her workflow and incorporate it into her teachings.

Her students are reaping the benefits of this as much as she is – graduating with a set of highly-sought after and directly-applicable experience: from CAD and 3D printing to creativity and adaptability.

Fostering Innovation through Interdisciplinary Projects

Callas’s curriculum has been largely influenced by her early experiences working at a makerspace.

“There was a student there who was in engineering, and then there was another student who was a nursing student, and I was there as an artist working,” she recounts. “To me it was really fascinating to work between the fields, and so I wanted that opportunity for my students.”

The interdisciplinary experience stuck with her and has impacted her teachings to this day. “It’s one of the things I really like about 3D printing and emerging technologies, that we can all work together in the space and maybe through touching shoulders we come up with better ideas or innovative ideas,” she says. “I feel like it really does foster innovation; in the arts, being exposed to the other fields, but also the other fields being exposed to the arts.”

Through cross-department projects with her students, Callas encourages the weaving of an artist’s touch into other fields, and vice-versa.

“With the Gigabot, we do a couple of different projects,” she explains. “[The students] have to go out and seek someone in another field that needs a 3D print, or may not even know they need a 3D print yet.” She’s had students work on projects with scientists, anthropologists, mathematicians, and chemists.

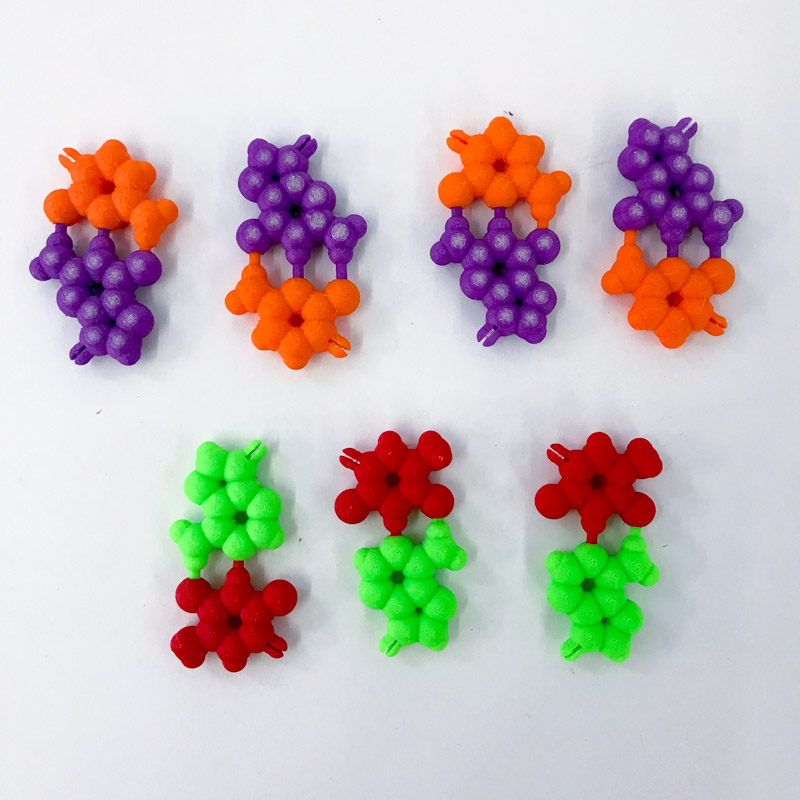

“Last semester, I had a student who was able to 3D model and 3D print a molecule that only exists when we make it on this campus,” she recounts. “That was really neat because the students were able to hold the molecule in their hand and look at it, and this is something they’ve been researching for a long time.”

Both Callas and Haug have a particular way of describing the tactile nature of 3D printing. For them, touch is inextricably linked to their craft, and so it’s no wonder that the transmutation of a concept from idea to digital to physical is so meaningful to them. But they also talk about it in a way that extends beyond the art world.

Haug worked on a project with a Monmouth professor to print out DNA in its building-block segments. “Her students will be able to break apart the actual double helix strand and…inspect the pieces that build them and see how they work together, how they link up, and how the actual double helix itself is formed, instead of just being able to look at the page in the textbook,” she explains. From a student’s perspective, Haug describes how this could function as a powerful teaching tool. “I know for myself, personally, when I’m able to feel things and actually look at things from all angles, that it helps me remember.”

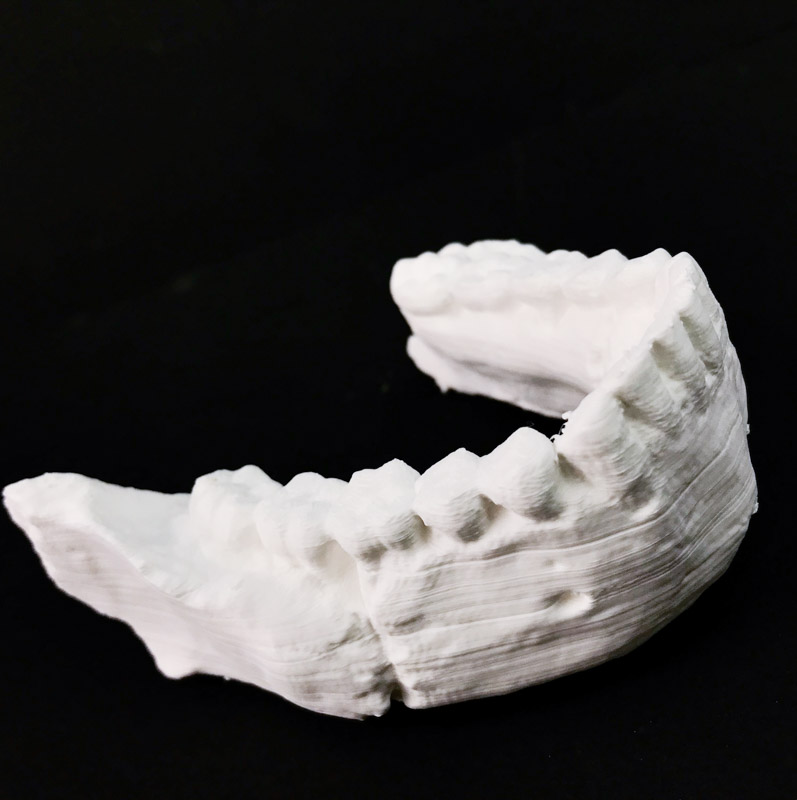

Another student of Callas’s took on a project in the anthropology department, 3D printing a mandible from a scan. “It was a newly-discovered mandible that showed that there was this new evolutionary line in humanoids,” she explains. The discovery was so new that it was still just being researched in a lab, but Callas’s student was able to get ahold of a 3D scan that the laboratory had taken. “We were able to 3D print it for our students to look at the mandible and be able to really examine and understand – ‘Why is this significant? What’s important about this?’ – by physically looking at it, which is what they would be doing in the field.”

It’s this sort of mentality that permeates Callas’ teachings: how does this school project translate into future real-world work? How does this degree cross over, post-graduation, into a career? It’s a deliberate, thoughtful, applicable style of teaching that one would hope every student gets the opportunity to experience.

Callas took her students on a field trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Media Lab, where students got a firsthand glimpse of what a post-graduation career path might look like. “The students just saw all kinds of possibilities in 3D printing and digital scanning,” she says.

Haug also describes the profound impact this trip had on her. “We got a little backstage tour of [The Met’s] digital imaging labs,” she recounts. “That’s [now] kind of a loose goal for myself to do work with an anthropological aspect to it, ’cause I think that’s really interesting. I really like working with both past and present, and…bringing them together in a way that everyone can be interested in.”

Adaptation in the Art World

Callas explains that what she’s doing in her classes is more than just teaching her students a software and a machine. Yes, her students come away with CAD and 3D printing experience, but what she’s really trying to impress upon them is a can-do spirit of versatility and flexibility.

“I think one of the things that’s really exciting about the students using the printer…is that sort of entrepreneurial mindset,” she says. “That adaptability is gonna be really important in their work life and going forward. And so 3D printing’s been really important for my students to… understand that this changes all the time and you have to change with it. You have to figure things out yourself, you have to Google it and use YouTube, and that self-direction is really important and I see a lot of growth in them through doing that.”

Callas is speaking from experience.

She got her MFA from the New York Academy of Art and her BFA from the Stamps School of Art at the University of Michigan. She’s been working as an artist in an age-old craft for decades, and yet has nimbly evolved as her field has undergone some major, rapid changes in the last several years.

“It’s been interesting to be able to watch something be introduced to my field of sculpture at this stage that changes it radically,” she says. “I liken 3D printing to when Photoshop was introduced to photography and Illustrator to design work, when everything went onto the computer. Well sculpture hadn’t been on the computer. And so what it’s done to sculpture has been unbelievably fast, so we’re all adapting quickly.”

Where Callas had to evolve efficiently and pick up a new tool midway into her career, she works to give her students a leg up by sending them out into the world well-versed in these new digital tools.

“I try to keep it integrated in every class,” Callas says, of 3D printing. “My big focus is being able to work seamlessly between the handmade and the digital. And I think that that is absolutely necessary for going forward in the world today.”

The old traditions and handmade touches will likely always remain in their own ways, but the injection of digital into the creation process is undeniably beneficial and here to stay. The message under Callas’s teachings seem to be: better to embrace this and prepare for it than to fight it. “I want my students to realize that the digital is going to be a big part of what they do in the studio, even though they still have the dirt and the dust and the plaster dust under their fingernails.”

3D Printing in the Artist’s Workflow

This fusion of digital and handmade permeates not only Callas’s teachings but also her personal work, where she uses the two mediums to complement one another.

“I work back and forth between the digital and the handmade the whole time,” she says. “Uploading drawings, and then uploading scans, printing things, sculpting from prints, sculpting from the models, scanning what I’ve sculpted in clay, going back into the computer, printing that…so it’s a real back-and-forth process.”

Callas has a long history of working in sustainability, something that has heavily shaped the work she does today.

“I realized when I was working in sustainability that people were having a hard time responding to just environmental data,” she explains. “But if it were a stream or something that they fished in as a child, then they would really protect that space. And so I wanted to find those more emotional connections in people, like where are our emotional and more intimate connections to nature and where do those exist?”

She began experimenting with incorporating local flora into her work, forming a body of work around what she called the “Ecological Self.”

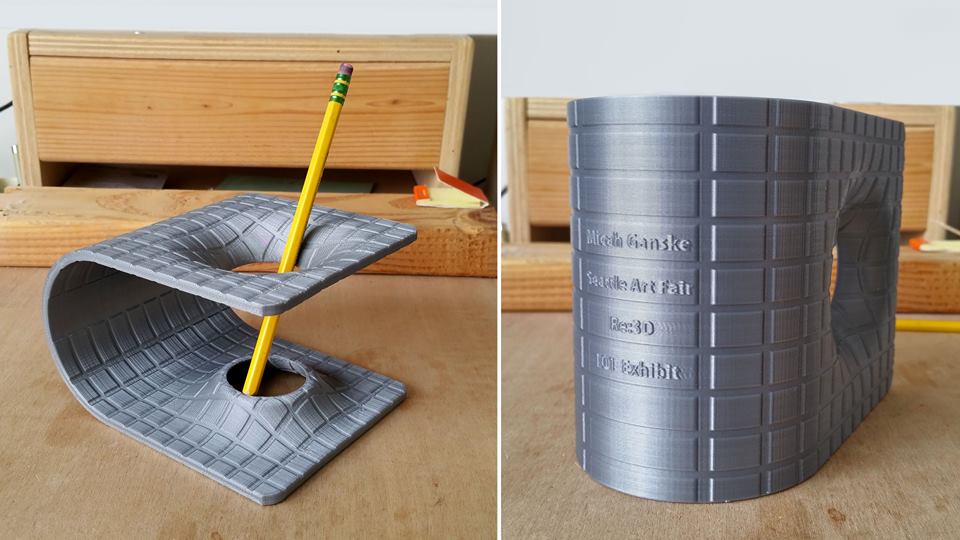

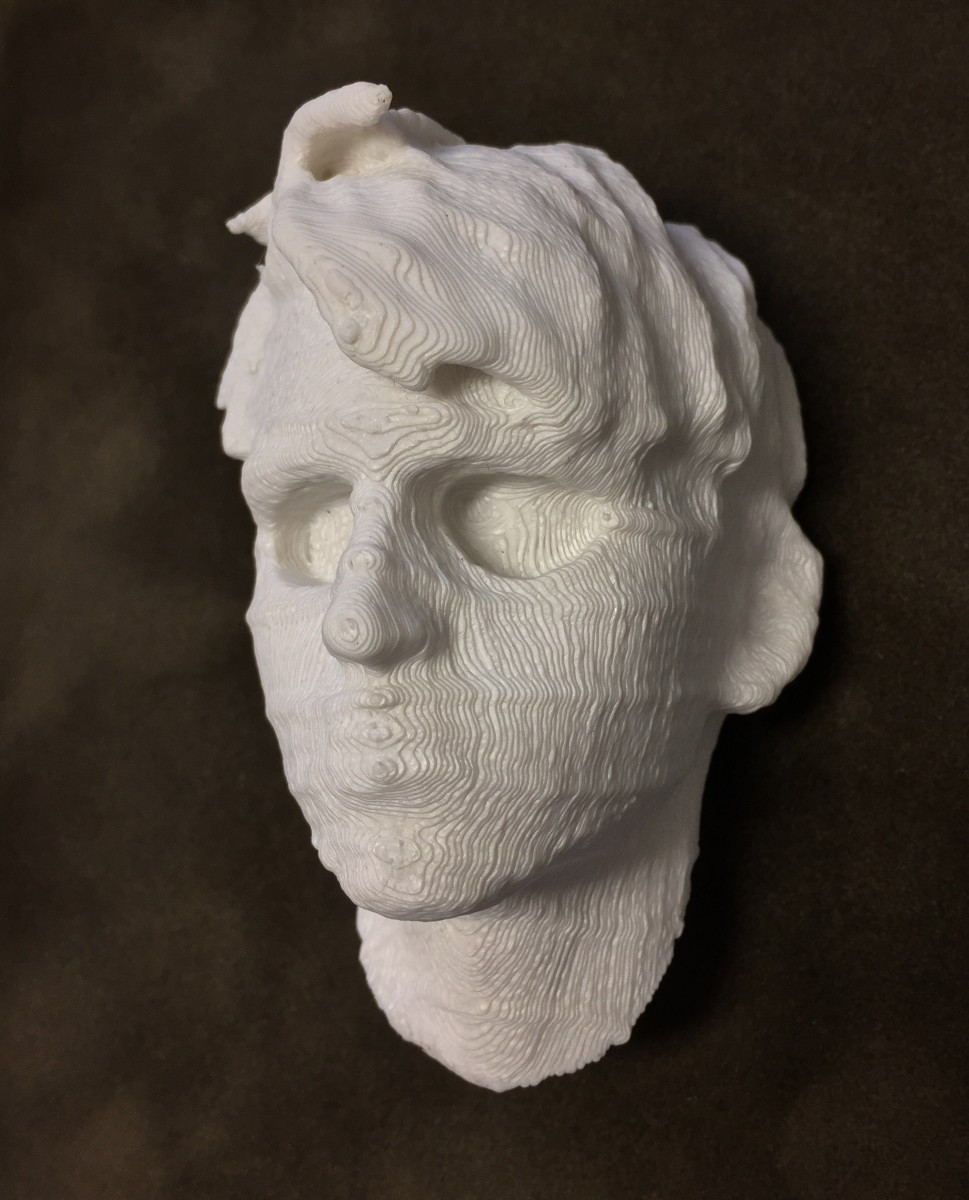

This ultimately evolved into her Eco-Portraits, a mask series in which she does a portrait of an individual around a symbol or pattern from nature that’s significant to that person. “I’m looking for that connection, where is that intimate link between them and nature,” she explains. “And then I take a pattern from that…and I combine it with a portrait.’

Where Callas used to work solely in the handmade realm, she’s found immense advantages with bringing new technology into her work.

“Before, I would sculpt from a model to get the individual portrait, and then I would sculpt and dig into the clay the different patterns,” she explains. “The way that 3D printing has helped it is now I can take a scan of my model and I can 3D print their head, and then I sculpt from the head. I still work in the clay, but I’ll be working from a 3D print of the model so they don’t have to sit there that long.”

“The other thing that’s been a huge advantage,” she continues, “is often when I want to get an intricate pattern into the clay and then I make the mold and cast it, some of that pattern gets disturbed and broken [and] needs to be repaired. And so with a 3D print, I’m able to digitally scan in my sculpture, get an intricate pattern without much repair work, and I can just 3D print it rather than cast it.”

There are several different aspects to 3D printing that have proven to be of immense help to Callas in her process of creation. “One is that you can change things really quickly, and so if you’re working digitally and you need to shrink something down or enlarge it or change any part of it, it’s much faster than working in clay,” she explains. “And also then you can get copies really quick. If you have to make a mold of a sculpture, it takes you quite a long time, but I can scan a sculpture in a couple of minutes, and then I can 3D print it very quickly compared to what it takes to cast from a mold. So those are some really big advantages.”

What Photoshop is to photography and Illustrator to design, 3D printing is to the physical, Callas explains. And what more valuable function is there in these programs than the undo button? This is a game-changer to which her field never previously had access.

“Oh, there’s no comparison…it’s so much quicker,” she says. “If I make a mistake or if I just don’t like something, I just undo it. But if I don’t like something in clay, I have to rebuild it, and it takes a long time.”

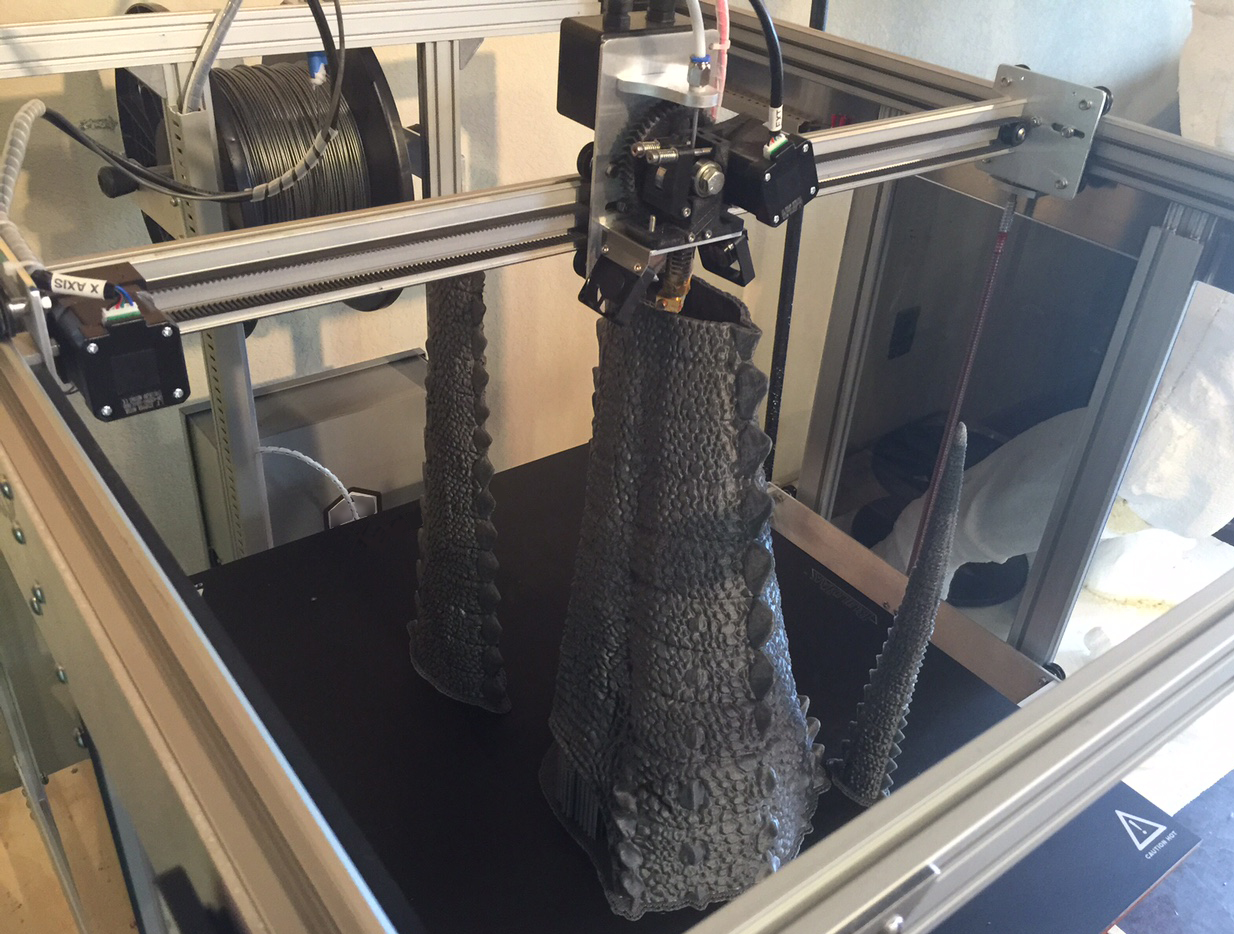

Callas’s current big project is 3D printing a life-size human sculpture with patterns from nature etched into the form – “almost tattooed into the skin” – representing how place shapes us and can very literally become a part of who we are through what we eat and breathe.

She completed an artist residency at an eco-art residency called Joya in Spain last spring – paid for in part by an Urban Coast Institute Faculty Enrichment Grant – collecting symbols and patterns from the wildlife there, which she will add to the 3D printed figure. She’s currently doing test prints for the body, which she estimates will take somewhere between 10-12 prints and 1,300 hours of print time.

While she still loves working in good old-fashioned clay, Callas can’t deny the time and labor savings that comes with adding a 3D printer to her workflow. “I still love working with clay, there’s something to it,” she says. “But I think some of the advantages which I’m looking forward to [include] emailing my file to the foundry rather than shipping huge molds or carrying them…” She laughs, and says of the artist community, “I think we’re going to end up liking that.”

Callas was recently chosen to be the new Artist-in-Residence for the Urban Coast Institute. During this two year appointment, she will be making 3D printed life size figures that combine ocean science with symbols from the ocean.

Inspiring New Career Paths

There’s no denying the impact that Callas’s teachings have upon her students. The interdisciplinary elements in her classes are opening her students’ eyes to interests and career paths that were previously unconsidered.

“I definitely want to pursue something with a sort of museum aspect to it,” says Haug. “I would really like to work with cataloguing and organizing.” She explains that she’s excited about 3D printing’s ability to increase accessibility to information and open doors to research.

“What inspired me to work with the anthropology professor was when they take fossil scans and they upload them to databases, so people all around the world can just print them out and be able to look at them,” she says. A bone segment that may live in a lab a flight away could instead be printed out in the comfort of one’s own facility in less time than it would take to travel there. “That is just remarkable to me,” she muses. “I want to be involved in that.”

Beyond inspiring her students to think outside the box and consider the possibility of applying their art degree outside the world of art, Callas also gives them the final piece of the puzzle: job postings.

“I’m always collecting job descriptions that include 3D printing and 3D scanning and digital modeling,” Callas says. “One of my students could walk right into a medical position with the scanning and the 3D printing [they learn].”

“If you had told me when I was in middle school that I could possibly work in the medical field, I would have told you, ‘What are you talking about? There’s just no way,’” says Haug. “I didn’t even consider the thought that this could be something that would be so interdisciplinary.”

A 3D printed eco-mask by Kimberly will be available at an upcoming auction at Sotherby’s in New York City, October 15th: https://kimberlycallas.com/take-home-a-nude-at-sotherbys-new-york-october-15th/

See more of Kimberly’s 3D printed pieces of work: https://www.artworkarchive.com/profile/kimberly-callas/collection/3d-prints

Morgan Hamel

Blog Post Author