2022 UPDATE: DEEP IN THE HEART IS NOW PYROLOGY FOUNDRY & STUDIO

It’s a sweltering, sunny July day in the small Texas town of Bastrop, and two men in what appear to be suits that you might wear to descend into a volcano are pouring what looks like lava from a cauldron.

I’m at Deep in the Heart, the largest fine art foundry in Texas, and I’m witnessing a bronze pour.

Clint Howard bought the foundry in 1999 and has grown it from five employees and 1,200 square feet to a team of 34 and about 22,000 square feet. “We’re like a publishing house,” he explains. They work with 165 artists around the world and turn their work into bronze or stainless steel monumental sculpture.

The bronze casting process – called lost-wax casting – is a 5,000+ year old art still being done in the same fashion as it was millennia ago.

“It’s a five generation process,” Clint explains. They start by creating the original sculpture, then making a mold on that sculpture, and then making a wax copy of the sculpture. A ceramic mold is made on the wax copy and flash-fired at 1,700 degrees to melt the wax out – hence the name lost-wax casting. With the wax gone, they’re left with a ceramic vessel that they can pour molten metal into, leaving them with the final sculpture.

Ten years ago, Clint decided that the business needed to start embracing technology.

“At the time, my focus was on 3D laser scanning and CNC milling,” he explains. “We got into the industry by buying a scanner and a huge CNC mill.” They would scan the sculpture and mill it piece by piece out of styrofoam.

“We did a lot of work for a lot of different artists in this technique,” he recounts, but, as he explained, “you still have to sculpt the whole piece full-size.” Clint describes the process as a huge “paint by numbers.” The styrofoam model gives them the outline and where the detail should be, but they still have to do all the fingerprint detail by hand with clay on top of the styrofoam form.

3D printing really wasn’t on their radar, Clint explains, until several years later.

Life Sized Dinosaurs

Clint got the fateful phone call four years ago from a dinosaur museum in Australia with a project proposal. “They wanted us to produce a herd of dinosaurs and they wanted to prove that it could be done all digitally,” Clint recounts.

The sculptures of the dinosaurs had been modeled in CAD, and the museum wanted Deep in the Heart to 3D print them in a material that could be direct-cast, circumventing “a whole lot of steps” in the casting process, in Clint’s words.

“Of course we had no idea what they were talking about or even where to start,” says Clint, “but they had done the research.” The museum had found Gigabot through Kickstarter and thought it would be an ideal fit given the proximity of the re:3D office to the foundry. “They basically said, ‘We want to do this – how many dinosaurs will this much money get us?’”

Deep in the Heart got their first Gigabot and quickly started experimenting how to best integrate 3D prints into their casting process. They ended up with 14 life-size dinosaurs – a nine-foot-tall, 13-foot-long velociraptor chasing a herd of smaller dinos – which now reside outside the Australian Age of Dinosaurs in Queensland, Australia.

The cost-savings of the project using the new 3D printing method were dramatic.

“To get 14 dinosaurs produced and installed for, let’s say, $120,000,” Clint says, “to do that traditionally – to have sculpted them full scale, to have molded them full-scale, and gone through the traditional lost-wax casting – we would’ve gone triple budget.”

"Unforeseen Benefits"

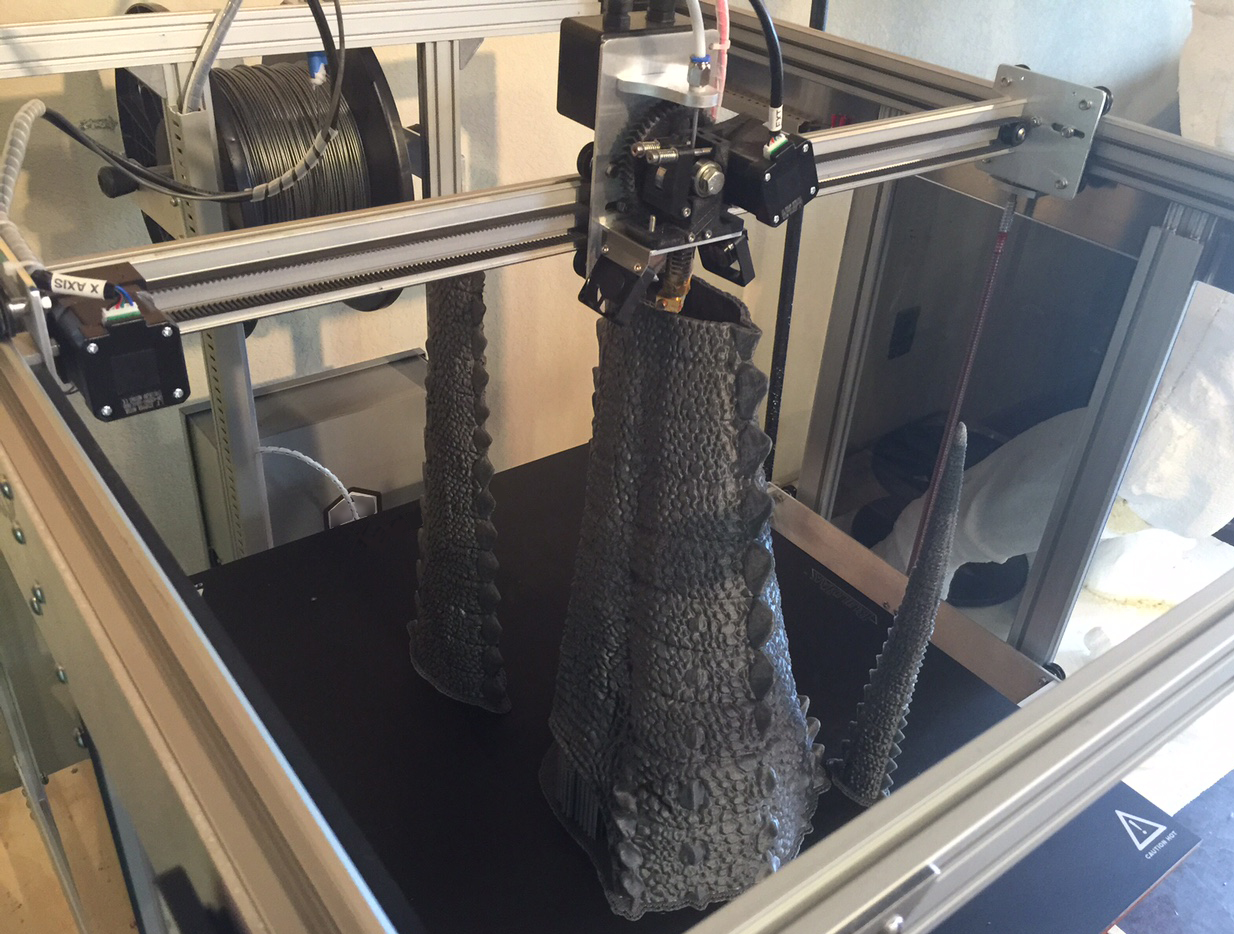

The dinosaur project was four years ago now, and Clint has since added two more Gigabots to their arsenal. “We bought the second one almost immediately and eventually decided we needed a third one,” he recounts.

Deep in the Heart’s specialty is monumental sculpture: their business is making really large pieces of art. “By having three [Gigabots],” Clint explains, “I can be printing three simultaneously, run them 24 hours a day, and it allows us the capacity to move a bigger piece through quicker.” They could do the job with one machine, he explains, but they want to move faster.

The benefits of incorporating 3D prints into their casting process have been unexpected and multitudinous.

“One of the unforeseen benefits of 3D printing that I really didn’t expect in the beginning is the consistency and thickness that we can generate in the computer is far superior to anything that we can do by by hand,” Clint muses.

The traditional method is less precise: pouring molten wax into a mold and pouring it out, or painting liquid wax onto the surface of a mold. “We’re trying to gauge that thickness by experience; which direction the wind’s blowing that day,” Clint remarks. “I mean, we’re trying and we can get fairly close, but we have variances within our thicknesses.”

This means they’re often using more bronze in a sculpture than is actually necessary – yielding costlier pieces – simply because the wax mold is made by the imperfect human hand.

Replace the wax mold with a 3D printed one, and the thickness is now precisely and uniformly set in the computer. “It’s going to be exactly that consistency through every fold, every detail,” says Clint.

“That really allows us to control our costs,” he comments. It also unexpectedly increased the quality of their casting, because with the 3D prints – as opposed to wax molds – “there’s no movement.”

“Wax is innately flexible,” Clint explains. Large sculptures are cast in many different sections – the massive buffalo they’re currently working on will be 30 or 40 separate pieces – and “each of those sections has the potential to warp slightly.” That means they’re often hammering and muscling the different pieces into alignment when it comes to assembling the final sculpture.

“With the 3D prints, they don’t move. At all.” Clint estimates that the assembly time of a monument that’s been 3D printed is about half that of one cast using wax molds.

The Rule of Three

“Most of the time when a commissioning party is asking for a monument to be made, they’re asking it to be a unique one-of-a-kind,” says Clint.

He explains that 99% of large sculptures out there start their life as a maquette – a miniature version of the big one. “That small maquette is where all the design work happens. It’s where all the artistic creativity happens.” The full-size sculpture is then just a mathematical formula of duplicating the miniature.

“Where 3D printing comes into play,” he explains, “is you don’t have to sculpt it big.”

They can take the small model, whether they sculpted it traditionally and then 3D scanned it, or whether they modeled it directly in the computer using CAD software, and they can print that model full-scale. This cuts out multiple parts of the process: they no longer have to sculpt full-scale, rubber mold full-scale, or make a a full-scale wax copy.

“I mean, you can literally just go straight from the printer into the ceramic shell process, and then you can cast.” The PLA material they print with burns out almost identically to wax, he explains.

It’s a huge time, energy, and cost-savings for them as a foundry. And for the artists, as Clint puts it, it allows them to go big faster. “It also allows artists to be more competitive because there’s not all those steps they’re having to pay for.”

Clint describes the cost savings rule of thumb as a “rule of three.” If a certain piece is going to be produced more than three times, “it might be cost-effective to do it the traditional method of actually sculpting the piece full-scale and making a mold on it,” he says.

“But if it’s going to be produced three times or less,” he explains, “the 3D printing route is cheaper.”

Where History and Technology Melt Together

“The cool thing about what we do is there’s always some historical significance,” explains Clint. “There’s always some story. What we’re doing is more than just an object.”

He’s referring specifically to the foundry’s focus at the time of this visit: a piece called The Splash, which is now installed in Dublin, California.

The sculpture pays homage to the role that a natural spring has played in the growth of the city, dating back to a Native American tribe. “The water is a very integral part of the city’s history,” explains Clint. “It’s also a very integral part of the native Americans that still live there, because the whole reason that this area was settled was because of this spring.”

The piece is 150 feet long: a large fluid-looking figure from which seven splashes emanate. Clint walks through the design: a water spirit has skipped a stone, causing these seven splashes. Each splash has a harmonic frequency superimposed into its face, which, Clint explains, is a “very specific part of the story.”

He goes on to recount that in the 1960s or 70s, the only surviving members of the tribe who still spoke the native tongue passed away. The tribe had lost their language.

In the 90s, anthropologists visited the area with wax cylinder recordings taken by anthropologists in the 1910s and 1920s who visited and recorded their language. “Luckily enough,” Clint goes on, “the elders in the community remembered their grandparents speaking the language enough to be able to help the anthropologists pull the language out of all of these recordings.”

Since this visit in the 90s, the tribe has now rediscovered their native language, and the sound waves on the surface of the bronze splashes pay homage to this.

“What we’ve got in all of these splashes is seven generations of members of the tribe saying ‘Thank you’ to the water spirit,” Clint explains. “That harmonic pattern is their voice frequency that was taken by technology, and then visualized in technology, and then superimposed on this sculpted splash in the computer, and then 3D printed so that each one of those splashes has the fingerprint of the voice of a [generation] of this tribe saying thank you.”

The impact of technology is woven throughout the story, from the rediscovery of the tribe’s native language to the creation of the sculpture to commemorate the role of water in the city’s history.

“It’s amazing,” Clint remarks. “Technology allowed it all to be created in the computer. The piece was 100% sculpted in 3D software and the monument has been 100% 3D printed and cast using the technology.”

Blending Old and New

It’s hard not to draw parallels between Clint’s commentary about the future of bronze casting and The Splash piece which his team produced.

The role of technology is steeped in both narratives. It’s been a tool, an enabler, a key to unlock a language and make a commemoration of that feat come to life.

And yet there can be pushback within the industry, resistance to the introduction of new technology that some see as a threat to the art’s centuries-old roots. “It’s a fine line to keep all of the ancient technology and the ancient techniques, and marry them with all this new stuff,” Clint comments.

But the basic process as the industry knows it is not going away, Clint explains. “We’re still going to have to go through casting the same way,” he says. “What I’m starting to realize in the industry is that the traditional method will probably never die.”

Yes, several steps of the process are replaced by a single 3D print, but the piece still must be sculpted – whether physically or digitally – the bronze still must be poured, the sculpture still assembled and given its artistic hand-touch. The heart of the casting process is still very much there.

“But,” he goes on, “right now, I have probably 6,000 square feet of mold storage. Those molds are susceptible to handling, they’re susceptible to human error, they’re susceptible to just degradation over time.”

He sees a not-so-distance future where molds are obsolete, where a quarter of his floor space suddenly and miraculously becomes free for other use.

“What the technology is leading me to believe is that very shortly, we’re going to have cloud based servers holding 3D files that represent the mold of the part,” he explains. “And now we can make that part any size we want. We can make it a little tiny miniature for a role playing game, or we can make it a 25-foot-tall monument to go in front of a casino in Vegas.” There’s no need to make a new mold for each varying size of a sculpture – it’s all done digitally – and the only storage space being used is on a hard drive.

Clint’s sights are set on the future, on the next generation of bronze casters.

“The artists that that are coming up and the artists that are going to be doing these monuments in 50 years, they’re all sculpting in the computer right now and they’re playing video games right now and they’re going to embrace that technology and that process.”

Clint has a profound respect for the age-old casting tradition, and he’s also a businessman. It’s his forward-thinking vision and willingness to dive into unknown territory that has helped him grow Deep in the Heart over the last nearly two decades.

“It is an amazing shift, and I definitely think that for the art foundries in the country to stay on top of it, they’re going to have to be embracing this technology and watching what’s happening and paying attention to all of these changes.”

Learn more about Deep in the Heart and their work on their website: https://pyrology.com/portfolio/

Morgan Hamel

Blog Post Author