Download our whitepaper on 3D printing and drones

Steve Brandt has been flying airplanes for 20 years. F15s and F16s, mostly, with ten years as a test pilot flying new systems for the Air Force.

Given his history, it’s curious to hear him describe the latest tenure of his career. “I always like to say I’ve flown more first flights since I’ve been here in [four] years than I ever flew actually flying airplanes,” he says, “because just about every airplane we build has never been flown before.”

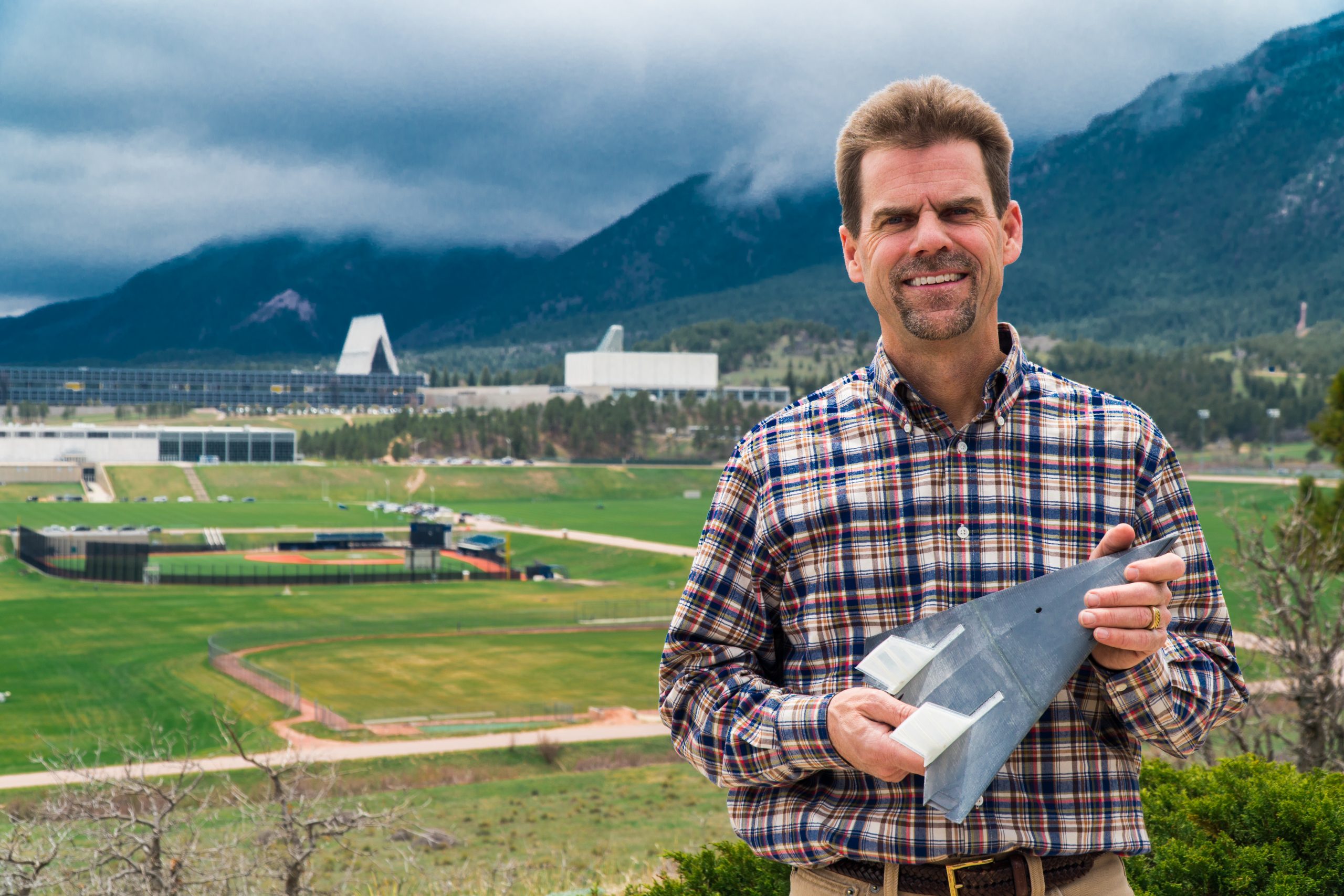

Brandt leads the Unmanned Aircraft Systems Flight Test Research at the United States Air Force Academy. The elite institution – perched idyllically in the mountains ten miles outside Colorado Springs – is home to just over four thousand cadets pursuing degrees ranging from business to engineering. They will also graduate as Second Lieutenants in the Air Force.

The experience cadets go through at the USAFA, Brandt underscores, is unparalleled – even among the ranks of engineering behemoths like MIT or Ohio State. “There’s probably not another undergraduate senior in college that gets this kind of experience,” he says. “The Department of Aeronautics here is definitely the most well-equipped aeronautics lab in the country, especially at the undergraduate level.”

The Academy is home to impressive manufacturing labs, multiple levels of wind tunnels – from lower-speed options all the way up to supersonic (Mach 4.5, or four-and-a-half times the speed of sound, or 3,425.43 miles per hour) – a huge airspace for flying, and a long list of faculty and researchers to mentor cadets through their studies.

Cadets march their way through the Aeronautics Major, which culminates in conducting a capstone project of designing, building, and flying an unmanned aerial vehicle, or UAV, under Brandt’s watch.

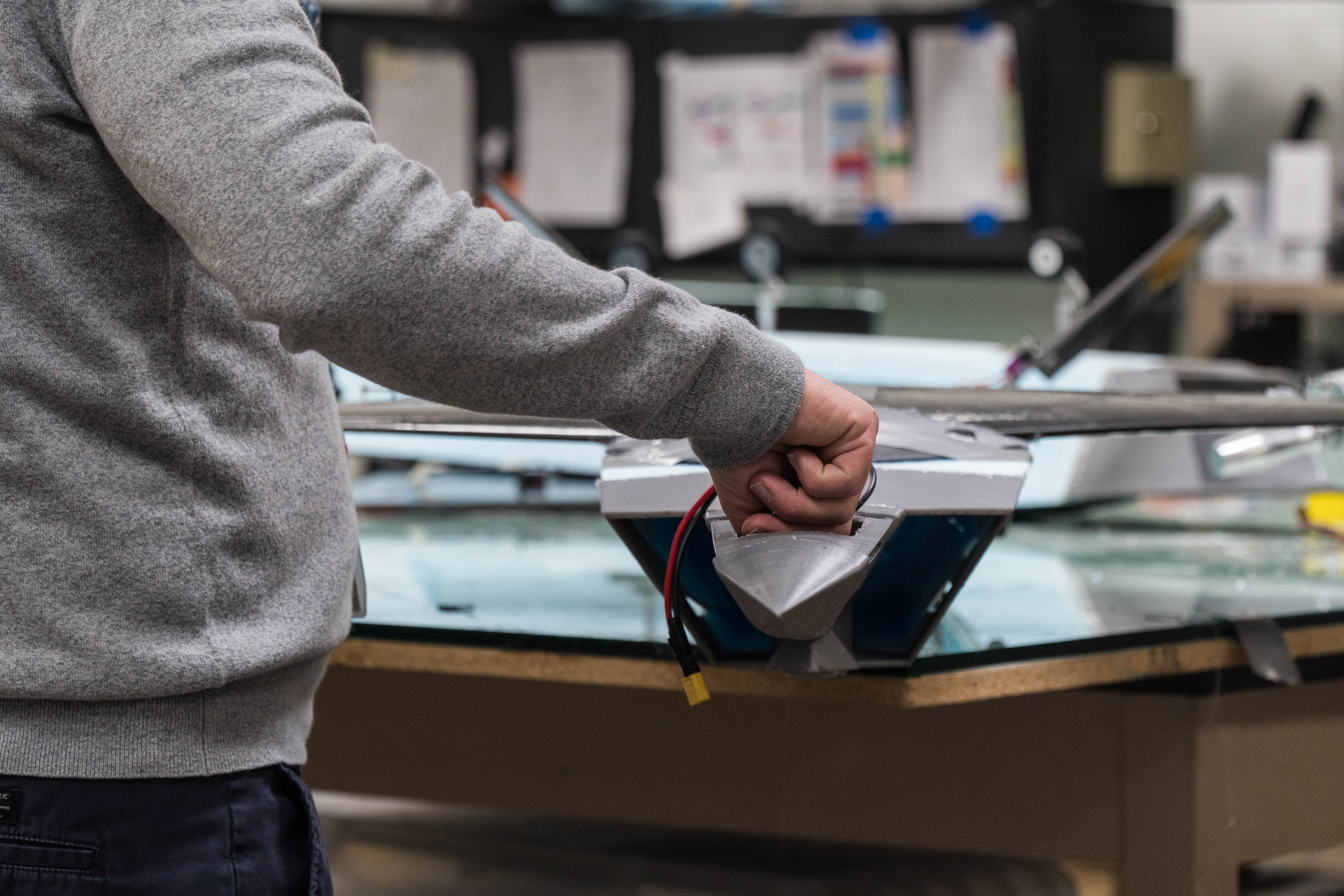

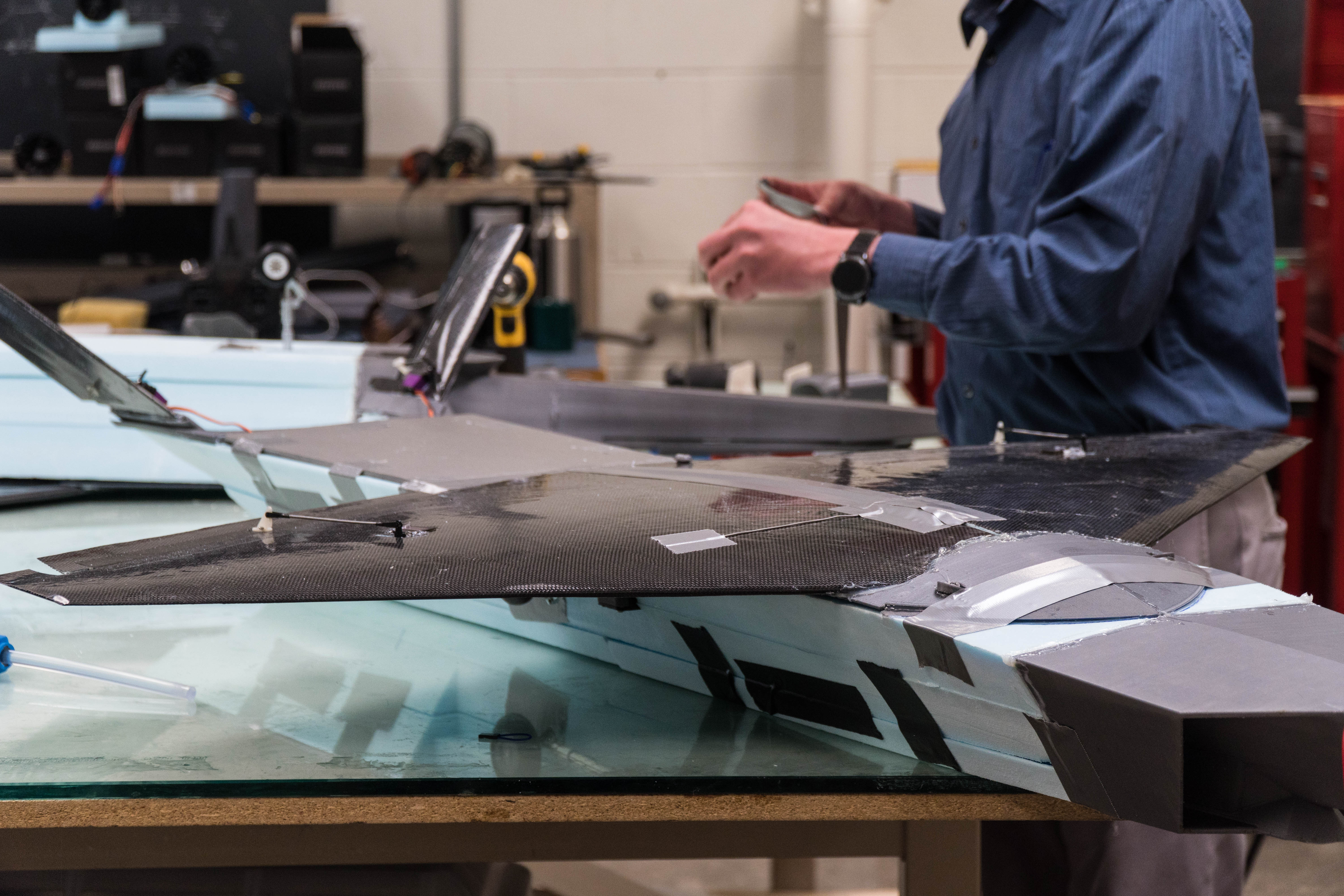

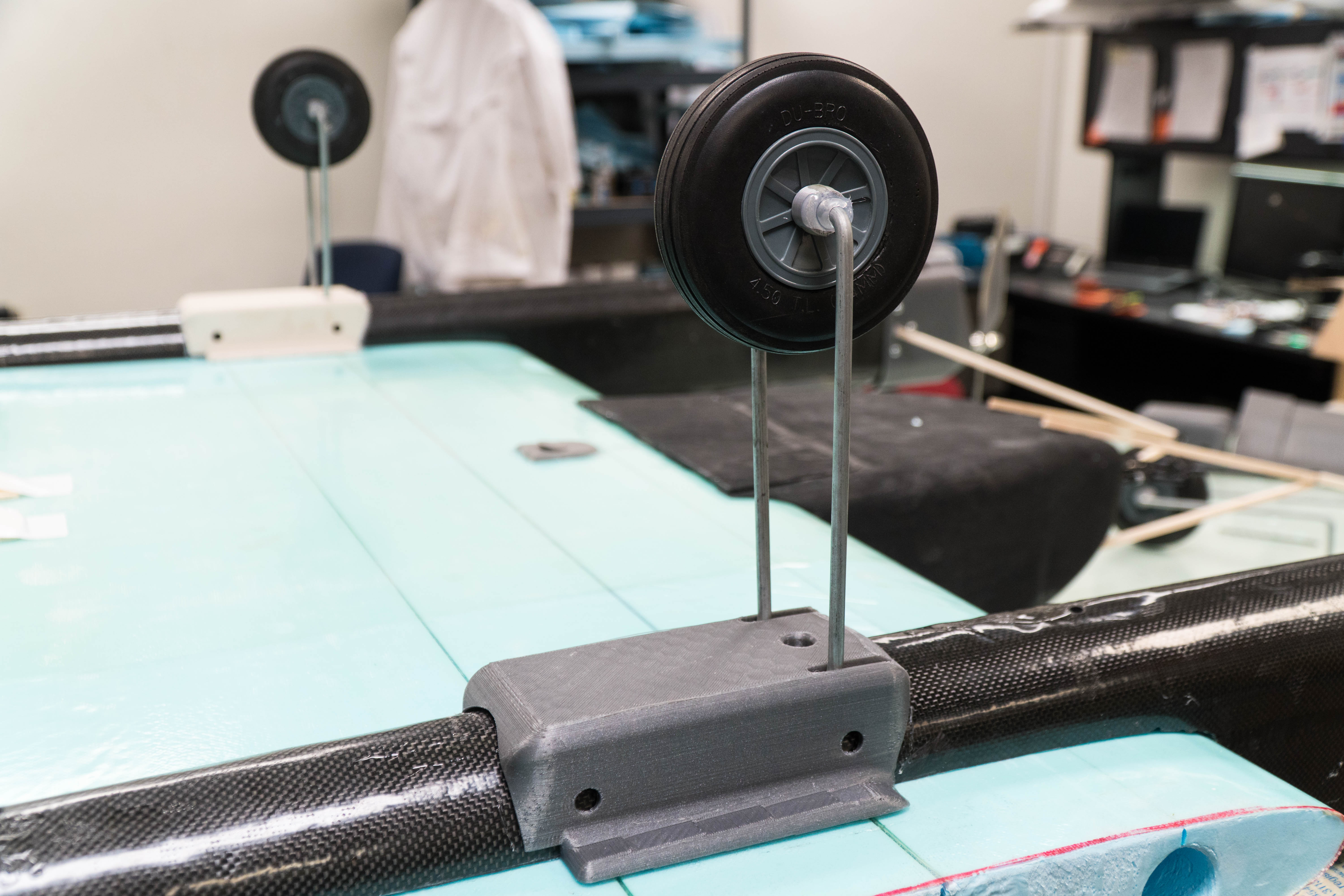

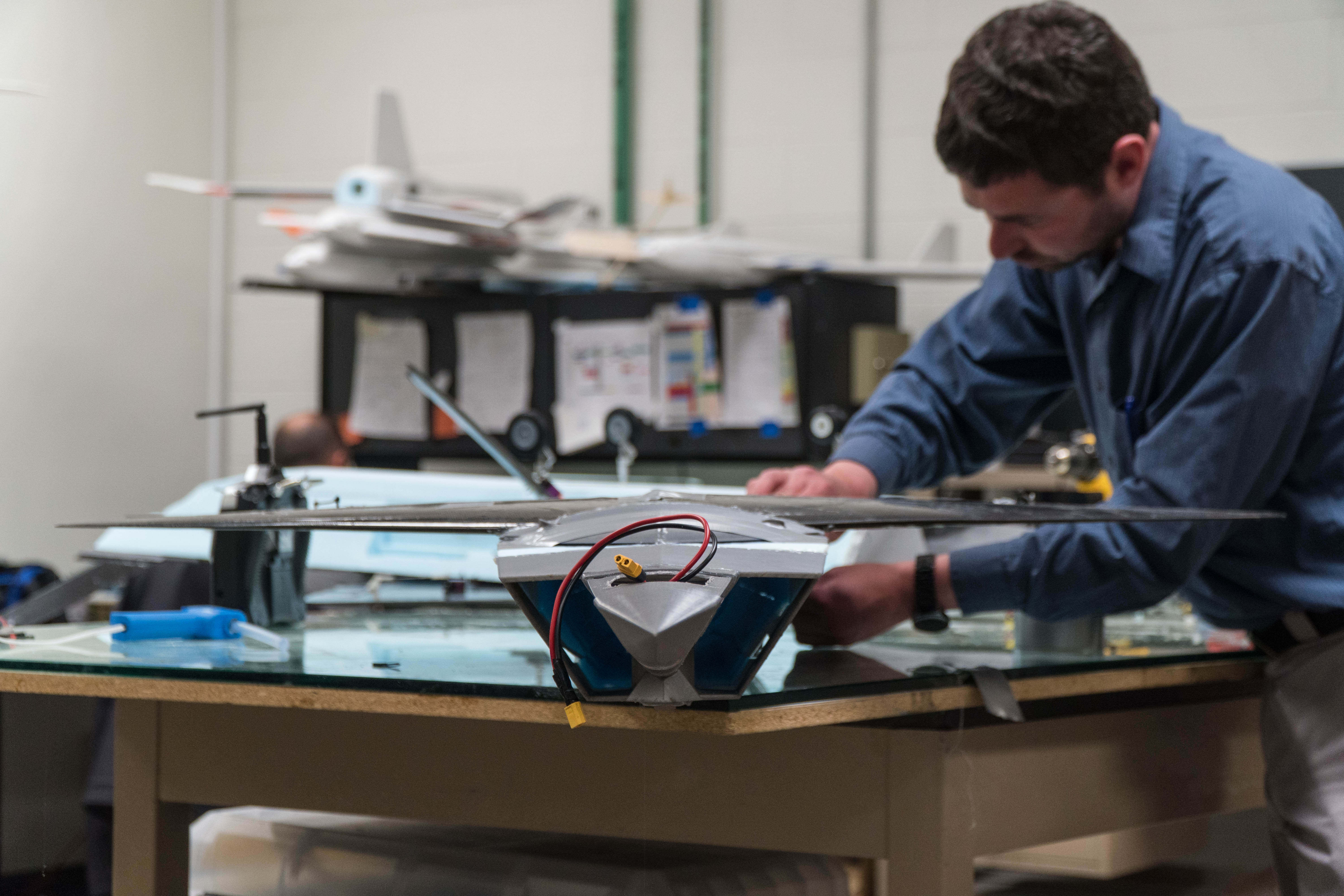

The aircraft that the cadets build and fly are not the balsa wood models of your childhood. They boast wingspans ranging from two feet to over five, retractable landing gear, jet and electric fan motors, and autopilot systems. They take off down runways, shoot off bungee cord launchers, and are released off the top of trucks while driving.

“Everything we do here in the design of the airplanes is not normal,” says Brandt. “It’s abnormal.”

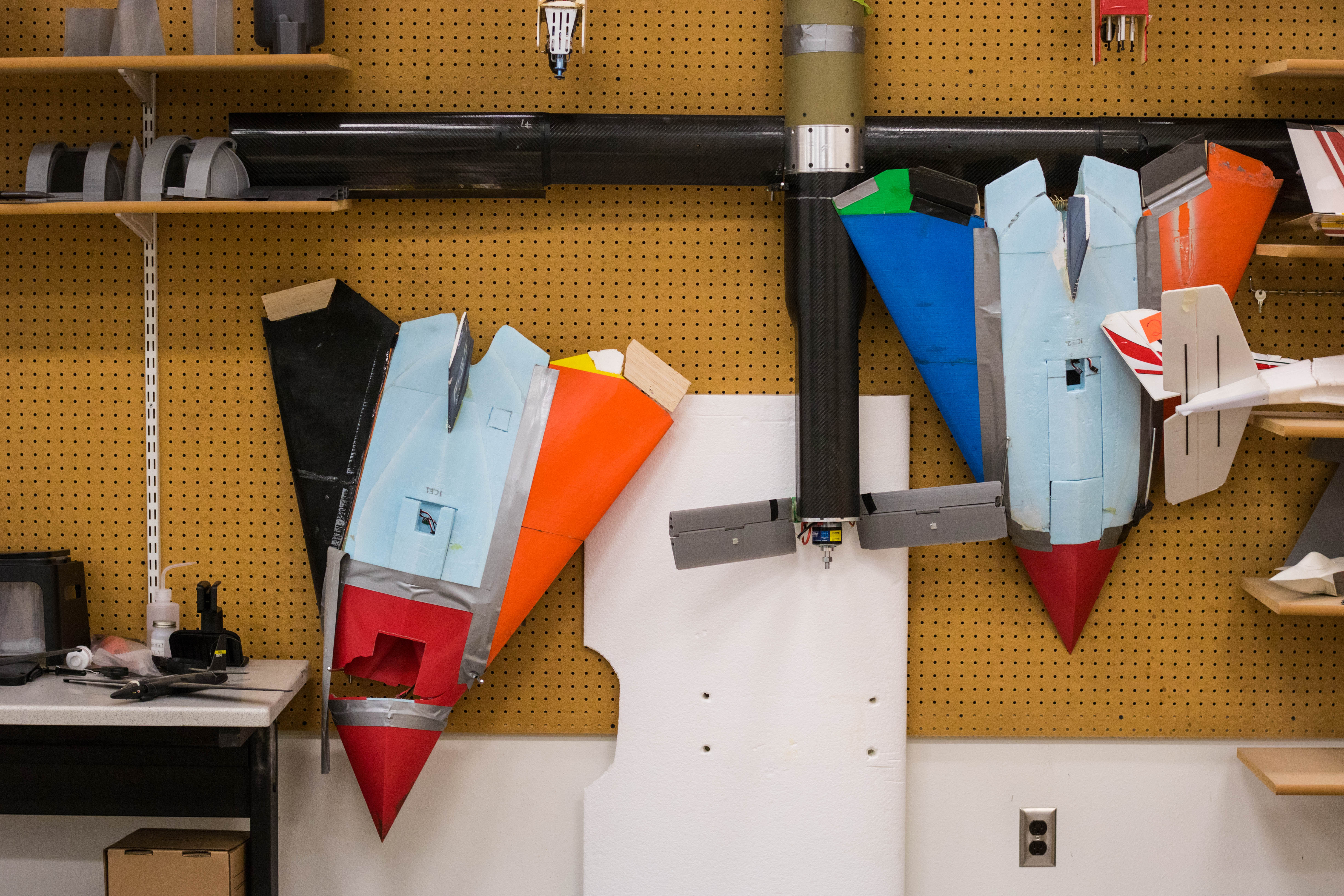

The aeronautics workshop is brimming with bodies of aircraft – spilling out of workshops and lining hallways and filling shelves up to the ceiling – that don’t exist in the real world…yet. “We’re doing cutting edge things. We’re trying to make airplanes do things that haven’t been done before,” Brandt explains. “When everything’s not normal, 3D printing is the solution, in so many ways.”

Designing One-of-a-Kind Aircraft

Lieutenant Colonel Judson Babcock is an assistant professor at the Academy currently teaching the senior capstone aircraft design course. This, he explains, is where students take on a project from a customer like the Air Force Research Lab and have the challenge of creating an entirely new, unique aircraft to meet a specific set of needs.

One such undertaking is a personnel recovery system: an airplane designed to rescue a fallen soldier from enemy territory using a retractable capsule released from the nose of the vehicle midair. Another is a supersonic air refueling tanker: a stealthy, high-speed craft capable of zipping into enemy airspace above the speed of sound, slowing down to refuel fighter jets mid-flight, and buzzing back to safety.

In the past, Babcock explains, UAV construction at the Academy typically happened in the mediums of balsa wood and foam. But with the unusual vehicles they’re making, traditional fabrication techniques are not always ideal. “Indeed, our students are making aircraft that have never flown before,” he says. “They’re unique shapes, unique designs, and unique structures.” All qualities, he explains, that render them “difficult to construct by hand.”

Pushing the envelope as they are, the Academy works to stay staying cutting edge with their facilities and technology. It was several years ago that 3D printing blipped on their radar.

Brandt and his colleagues in the aeronautics and mechanical engineering departments were researching methods that could increase their efficiency and accuracy in the aircraft design process. “Pretty much everything we design has got uniqueness to it,” he explains. “We can’t go buy something off the shelf.”

Brandt was aggressive about bringing 3D printing to the Academy for the technology’s ability to manufacture parts quickly and accurately: the technology could give them the ability to create these unique components in-house for rapid prototyping of aircraft.

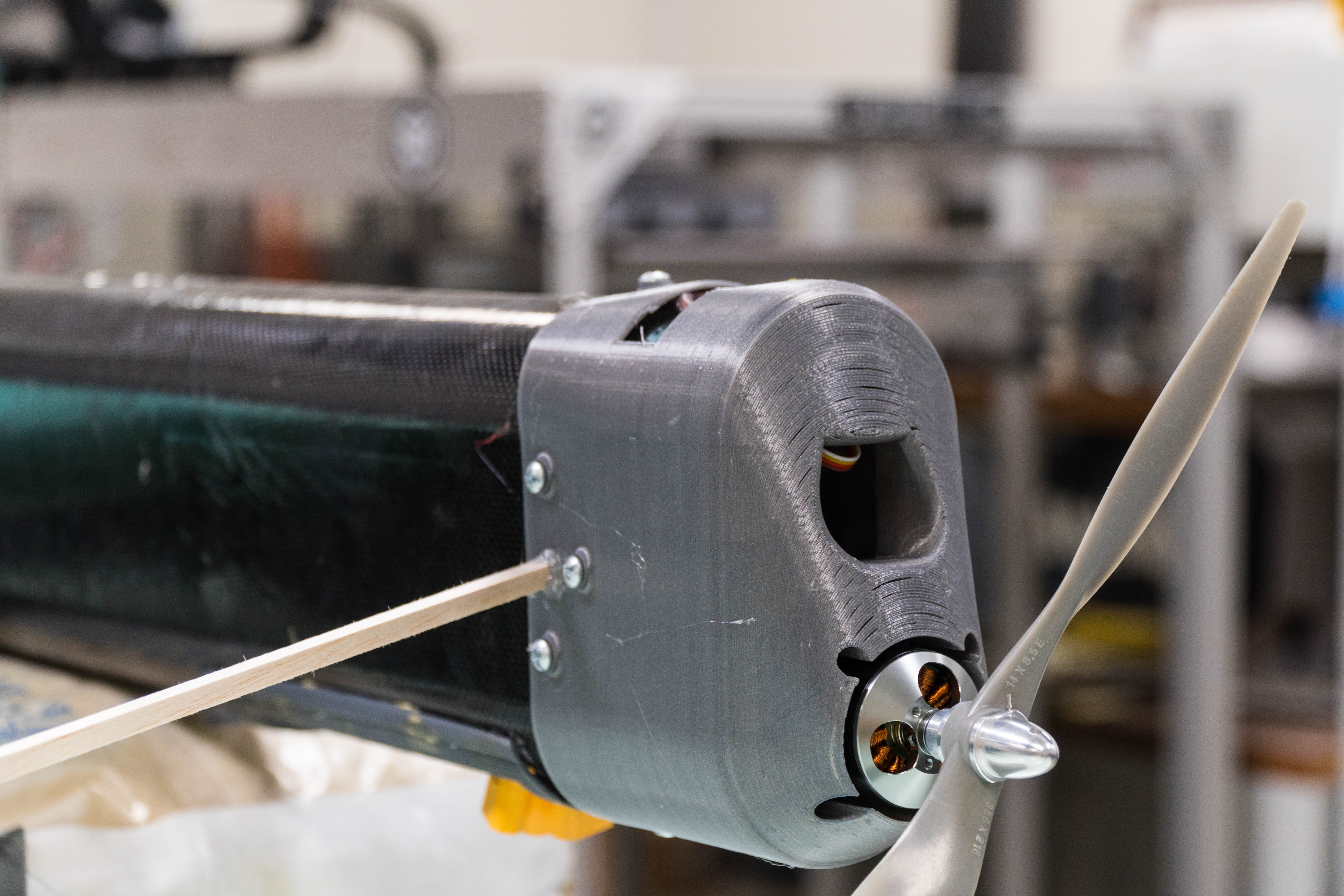

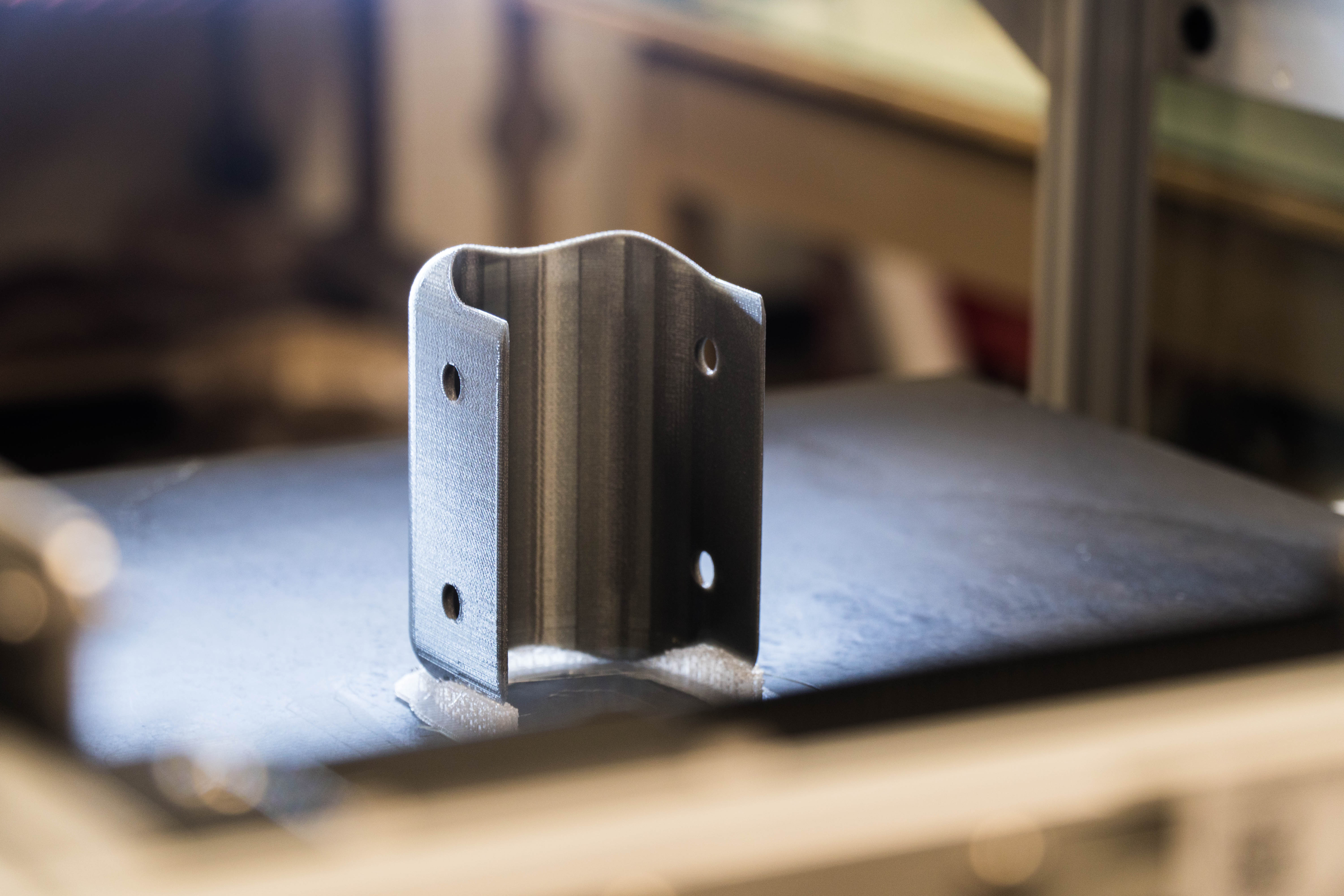

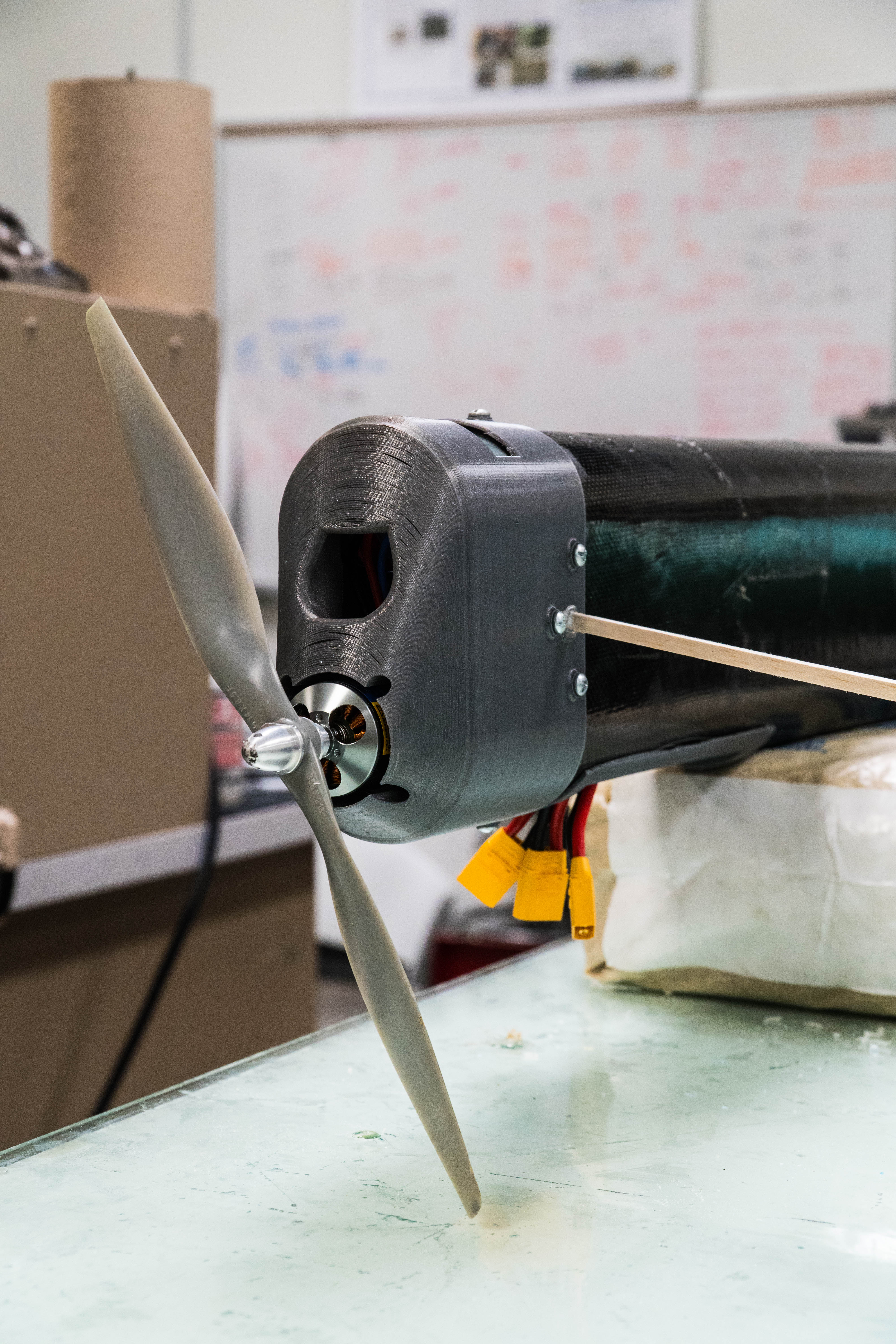

“The value added to being able to print the parts over anything else is that there’s detail that can be made without flaw,” he says. “I can build holes exactly where I want the holes to be for a motor mount; I don’t have to machine it out of a piece of aluminum and spend a lot of hours and it be a lot heavier than it needs to be.”

As the Academy set its sights on bigger planes – “things that are two, three feet in breadth, and two, three feet tall,” Brandt recalls – he began looking for a printer with a build plate to match.

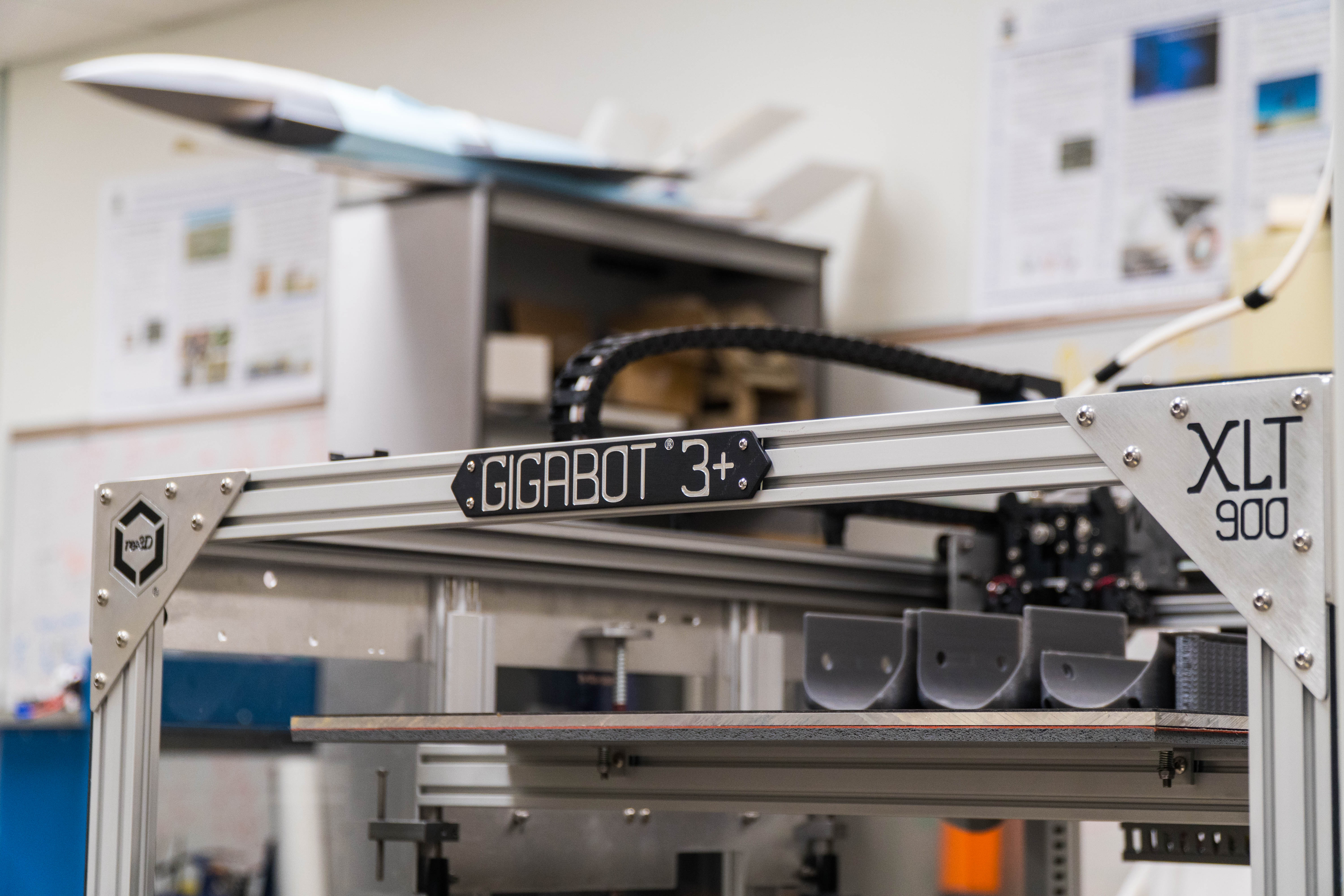

“I found the Gigabot, and it was the only big printer that I could find that had the volume that we started to think towards,” he recounts. Brandt saw a large-scale 3D printer as their ticket to print bigger sections of sizable aircraft with ease. Rather than having to break a component into multiple pieces to fit onto a small printer bed and connecting the parts post-printing, they could print entire plane sections in one go.

“When I found [Gigabot], we sat around and said, ‘Should we make this investment?’ One of our machinists said, ‘If we’re going to do it, get the biggest one, because you’re not going to want to print smaller.’”

Incorporating 3D Printing into the Airplane Design Process

The Air Force Academy invested in a Gigabot XLT, and with it, over 14 cubic feet of build volume. The printer purchase has paid off.

“To say that we use our Gigabot all the time is pretty much an understatement,” Brandt laughs. “It runs every day; there are times when it runs non-stop for three weeks.”

They use 3D printing to produce a multitude of parts in a variety of steps throughout the aircraft design process.

The first phase is the wind tunnel. Cadets take the CAD model of their concept craft, print it, and subject it to the rigors of wind tunnel testing to assess its aerodynamics in advance of flight. “We can validate the design in a wind tunnel with a 3D printed model, and then take it to the next scale and validate the fact that what we learned in the wind tunnel is accurate,” explains Brandt.

Once they confirm that the aerodynamics and stability of the aircraft are suitable, they’ll take the same CAD model, scale it up, and construct it with the help of 3D printing. Brandt goes on, “The only way to do that is to be able to develop the same airplane at a larger scale, and that requires a big printer that allows us to print larger parts so the accuracy is there in the design.” The successful scaling-up of a wind tunnel model is really only possible in the age of CAD and 3D printing. A balsa wood or foam model may pass wind tunnel testing only to fail on the runway because its larger, hand-constructed cousin didn’t quite match the geometry of its wind-tunnel brethren.

Fuselage, tails, motor mounts, landing gear interfaces, control services for wings: all of these unique components are printed and assembled – along with batteries, servo motors, autopilot, and carbon-fiber-wrapped foam – to create a fully-functional aircraft.

“We can take the novel designs that our students create, put them on a 3D printer and assemble them together,” explains Babcock, “and we can have a totally unique design – a new aircraft that the world has never seen before – that hopefully meets the requirements that the customer gave us when we set out on that process.”

The Benefits of 3D Printing in UAV Testing and Design

3D printing is now a staple within the USAFA Aeronautics Department, and with it has come a bevy of benefits.

“We break airplanes a lot,” explains Brandt. These are planes that have never flown before that may take a little practice to get the hang of operating. Babcock echoes the sentiment. “Part of the learning process our students go through is failure,” he says. “Inevitably, when they’re creating an aircraft, something will happen and the aircraft will crash or be damaged in some way.”

Because of this, both Brandt and Babcock stress, the cost of plane production – in the form of both raw materials and labor – is extremely important to the Academy.

“That’s where 3D printing really has an advantage for us,” says Babcock. “Typically it would cost hundreds of dollars to produce scaled models of these aircraft. With 3D printing, we can produce a model on the order of $5 instead of $500. It’s literally 100 times cheaper than other construction methods we have available to us.”

Turnaround time is also of concern. They’ve found that 3D printing allows for quick crash fixes in addition to rapid design iteration in the early development stages.

“It happened this semester with my cadets,” Babcock recounts. “We put their aircraft in the wind tunnel, and it didn’t have the stability that they had predicted before we printed the model. We had to make a design change.” The group went back to the drawing board with their CAD model, made some tweaks, and printed a new prototype for the wind tunnel. The plane was ready for re-testing by the next class and passed with flying colors.

Staying on schedule is crucial not only given the cadets’ looming graduation day, but also for the customers who are ultimately relying on the results of this testing to move forward with a real-world project. Babcock adds, “It’s only because of 3D printing that we’re able to do a rapid turnaround on our design iterations and solve problems fast enough so that we can get to the goal of actually flying a prototype for the customer.”

Once cadets’ planes progress past wind tunnel testing, 3D printing also comes into play as they begin flying outdoors for the first time. The technology allows them to quickly repair crashed crafts and get them swiftly back in the air.

“One of the beauties of having a 3D printer is I can get a part at two in the afternoon, I can slice it, get it on the printer, it can print all night, and by the time the students come back the next day, they have a part in their hand,” says Brandt. “That’s the way the world works today, and that’s what we should be showing them.”

The technology functions as on-demand inventory when they have to mend broken aircraft. Once the CAD file is created, there’s no manual labor, nobody whittling balsa wood into the wee hours. “With 3D printing, we have a repeatable process that is hands-off where we can manufacture the replacement parts we need on an as-needed basis,” Babcock explains. “We don’t need to do a large bulk order of parts in advance; we can print new parts to repair the aircraft as accidents happen.”

A Challenging Atmosphere

“One of the biggest challenges of building airplanes, especially at the scale that we fly them: every single ounce matters.” Brandt explains that cadets have an extra obstacle working against them: they’re flying in a challenging atmosphere – literally.

The Academy sits at 7,200 feet elevation. It’s more difficult to take off and fly an actual airplane in these conditions, let alone a small vehicle that doesn’t have the capacity to carry a large engine. “Developing lift – which is what we need to do – is harder at this altitude,” says Brandt. “It’s a very challenging place to fly, yet we do it pretty successfully over and over.”

“And the speeds?” He smiles. “They’re fast.”

The aircraft they’re building are typically in the range of five to fifteen pounds, cruising at speeds between 30 and 80 knots – roughly 35 to 90 miles per hour. So not only do their designs need to be lightweight, they need to be strong.

3D printing affords them the ability to design and create parts in a way that traditional manufacturing or hand construction often does not, and also to adjust print settings to maximize a component’s efficiency in both volume and weight. “A 3D printed part can meet all of those contours, yet still have the strength that we need to be able to put it on an airplane and have the structure that we need to fly,” says Brandt.

Enabling Innovation with Cutting Edge Technology

3D printing is a relatively recent addition to the arsenal of manufacturing capability at the Academy, yet the headway they’ve made since bringing the technology on board is impressive.

“This capability here has really just been developed over the past four or five years of building airplanes at the volume and scale that we’re doing,” says Brandt. “We used to get three or four – maybe five – airplanes built a semester; maybe two or three of them would fly – maybe.”

Now, he explains, they have the means to significantly increase both the quantity and quality of production. They’ve essentially doubled their numbers – building, by Brandt’s estimates, somewhere between eight and twelve airplanes a semester. “And why can we do that? It’s because we have the design tools and the manufacturing tools to do it.”

It’s a boon not just to the Academy but also their customers – like the AFRL – who rely on their aerospace expertise. “I think the most invigorating thing to me is that we provide – as best as we can – a product to a customer in a very short turnaround time,” says Brandt. “3D printing has enabled us to build airplanes that are what the customer wants. The only way we do it with the level of precision and accuracy that we do it today is because 3D printing has infected it so much.”

Inspiring Future Airmen

At the end of the day, the Air Force Academy is just that: an academy.

Its mission is “to educate, train, and inspire men and women to become leaders of character, motivated to lead the United States Air Force in service to our nation.” And what better way to do this with the next generation of pilots and flight engineers than with the challenge of designing, building, and flying a unique aircraft that solves a real-world need?

“When you design an airplane, it’s built on a computer screen somewhere,” Brandt muses. “We’re going to take that CAD drawing and turn it into a real airplane. It suddenly jumps off the screen, and now they’re holding a real piece. The fact that we can do that quickly with a 3D printer is amazing.” Babcock has also seen how the technology has impacted the learning process for cadets. “It really makes the world come alive for them.”

When the cadets’ planes finally leave the theoretical realm and go wheels up, “the whole learning loop is closed,” explains Brandt. “All of the learning comes together, and they go, ’Wow, I really do understand how an airplane flies, I understand how it works, and I also understand that – even at this small scale – these things are very complex.’”

The majority of the USAFA graduates will go on to become pilots. This experience of designing and flying scaled-down jets, Brandt explains, “gives them a greater appreciation for how those things operate, and the complexities that they inherently have inside of them.”

As for the “inspire” portion of the equation, Babcock has seen enough cadets go through the process to understand that box is being checked.

“You have to realize these cadets have worked for four years in an extremely demanding environment: extremely rigorous academics combined with extremely rigorous military training and athletic requirements,” he explains. “In their last semester here in this capstone design class, everything comes together, and they design and build an aircraft from scratch that has never existed before to meet a unique customer need.”

Toward the end of the semester is when they first send their designs skyward. “When it actually all comes together and works for the first time, you just see it on the students faces,” explains Babock. “It’s an indescribable feeling where all of their four years [have] come together to reward them with this moment where they’ve actually made an aircraft and flown it. And it actually matters because there’s a customer out there that needs this aircraft to meet a certain requirement. It’s really a special feeling for them.”

Brandt recognizes that the Academy has taken a lot of chances as they plumb the boundaries of what can be done with regards to new aircraft development.

He references back to his statement about the unparalleled educational experience that the USAFA provides, even when compared to other top-tier engineering institutions of the country. “Their level of innovation is not the same as what we do here,” he adds. “We take big risks because we want great return, and we’re willing to take those risks to give the cadets the best experience that they’re supposed to get at the Air Force Academy.”

Brandt and Babcock both reflect on the profound effect that 3D printing has had at the Academy, for cadets as well as the customers for whom they’re creating aircraft.

“In terms of performance and reliability and cost,” says Babcock, “3D printing has changed how we operate around here for the better, because it’s beat all of the previous methods hands down in all of those categories.”

Morgan Hamel

Blog Post Author