Ever thought about offering contract prints with your Gigabot, but struggled to identify a way to quote filament costs?

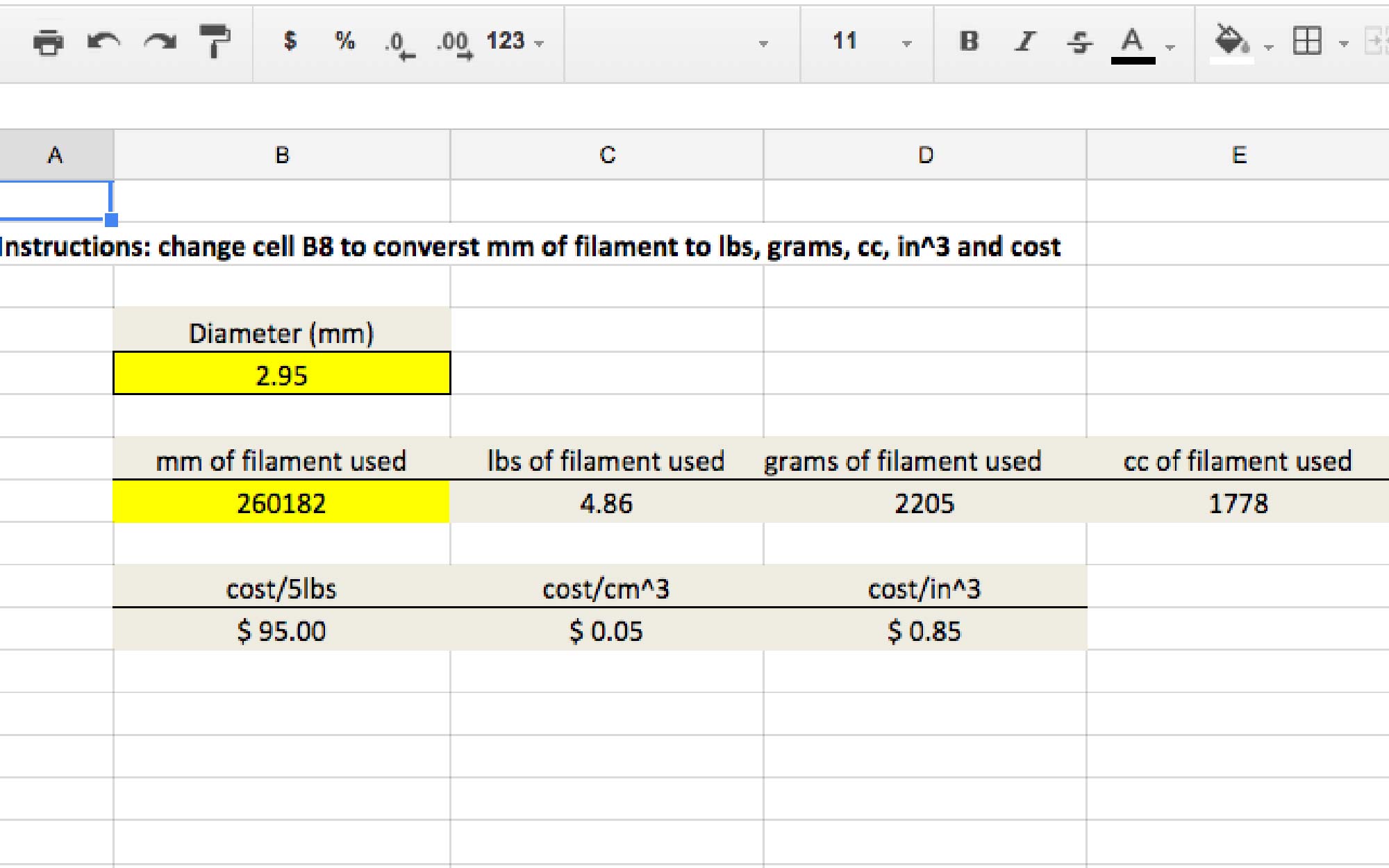

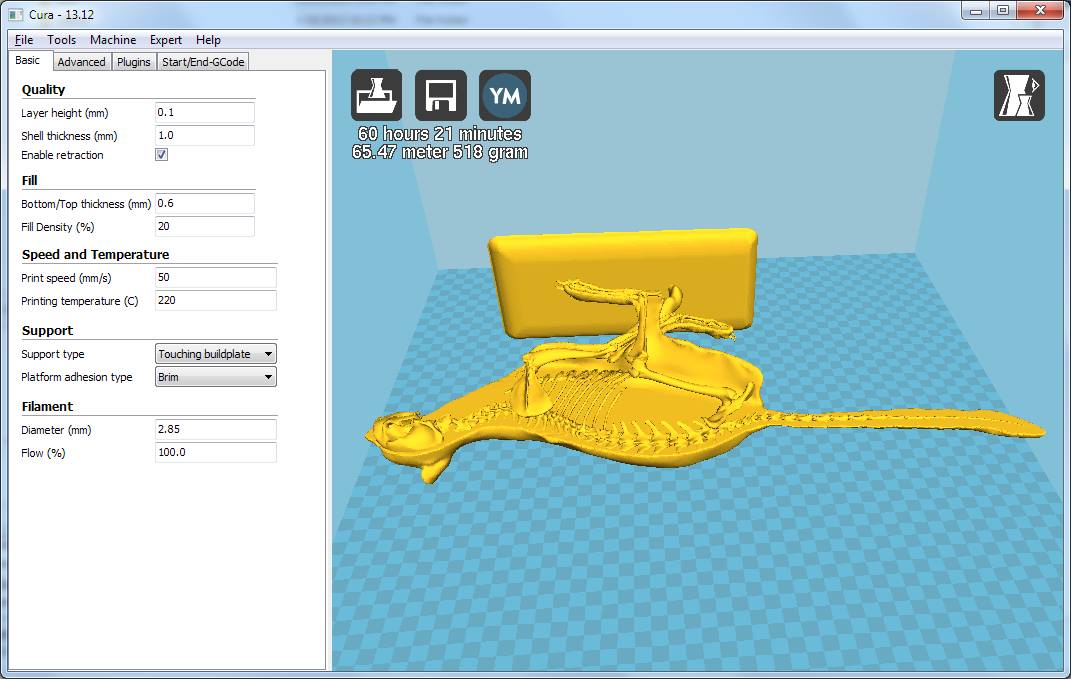

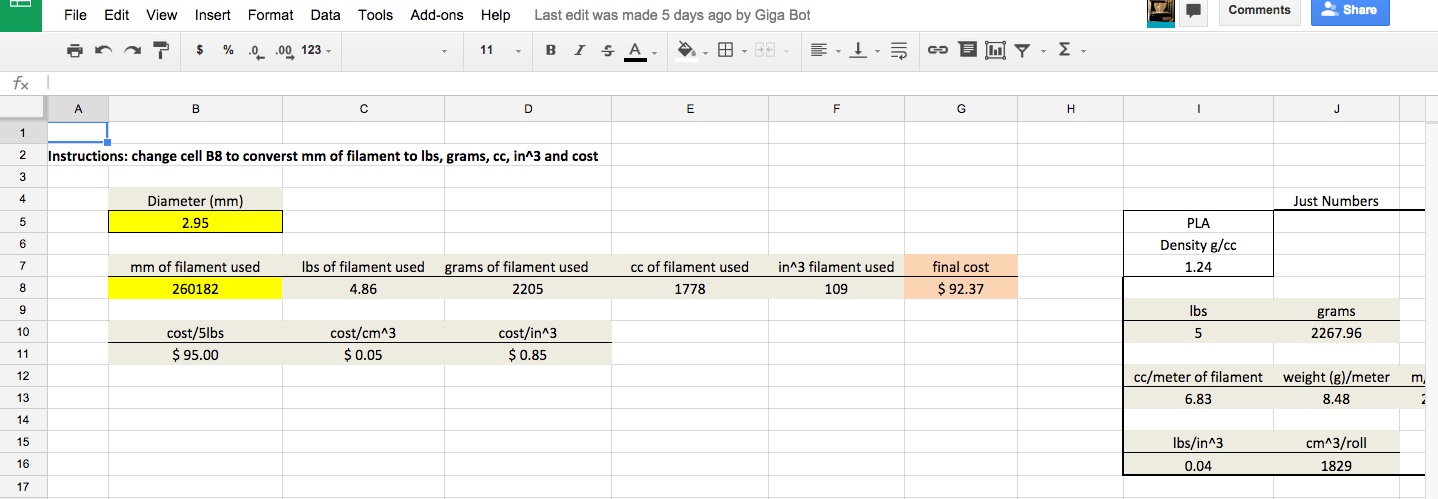

Inspired by frequent requests, our Chief Hacker designed this helpful tool to figure out filament overhead. By simply entering the true filament diameter (you’ll need calipers for this step), cost of the spool (don’t forget to include shipping!) and the amount of filament used, you’ll get a rough total cost.

You may also want to consider potential design time and opportunity loss during printing when Gigabot is occupied. However, by calculating the material costs you’ll be one step closer to gauging overall costs per print.

Need Feedback? Email engineering@re3d.org

Katy Jeremko

Blog Post Author