When computer programmer Dallas Kidd was growing up, she wanted to be an astronomer.

“But I realized as a kid,” she said, “that I didn’t know what that meant, because I didn’t know any astronomers. So I decided I couldn’t do that.”

In high school computer programming classes, when other students were creating financial programs for banks, she again felt discouraged. She thought, “I didn’t know how to do that, so I guess I can’t have a career in this.” It took a long, circuitous journey to get where she is now. “I spent years figuring out what I wanted to do, and if someone had just been there to say, ‘Hey! I’m an astronomer,’ or ‘Hey, I’m a computer programmer. You can do this and here’s how!’ to make it real. I would have done this forever ago.”

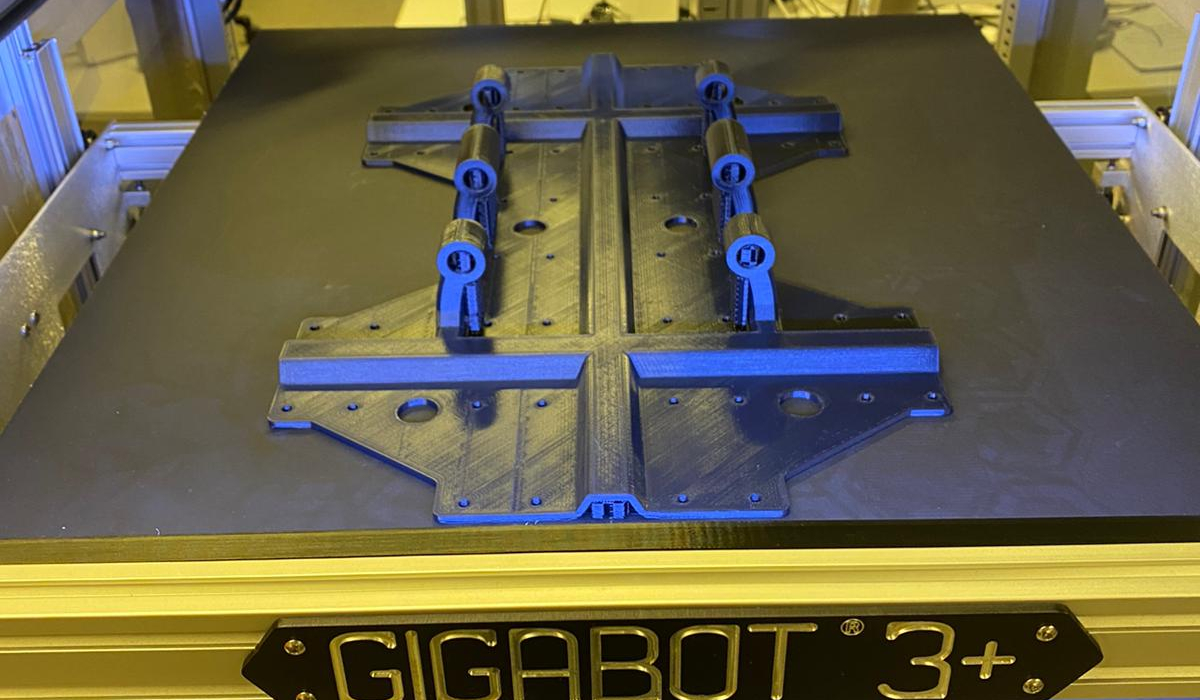

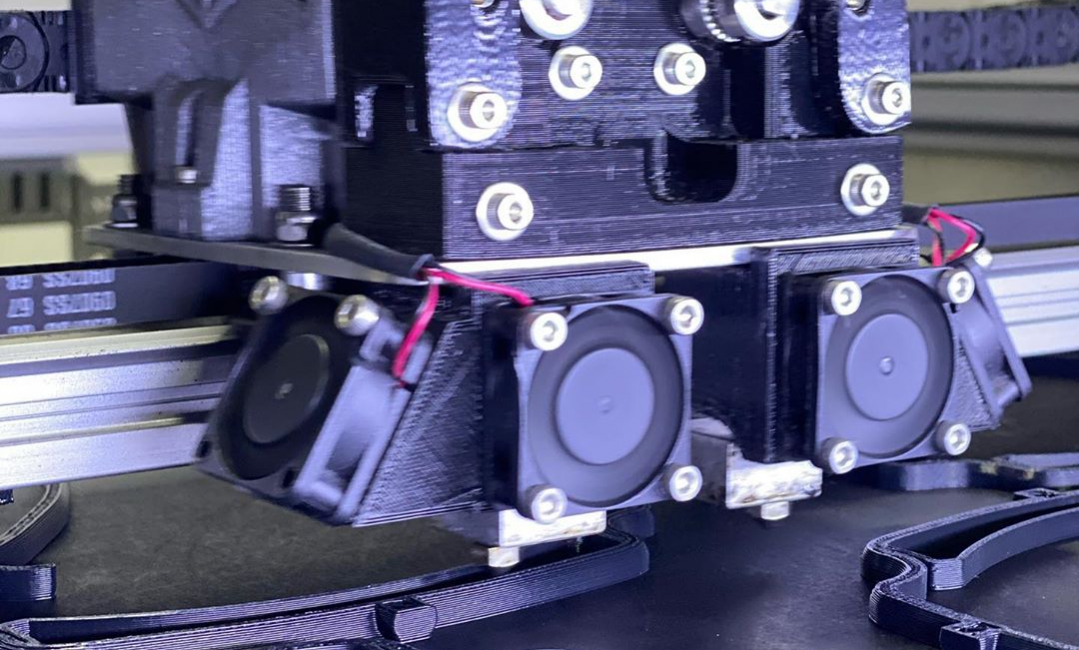

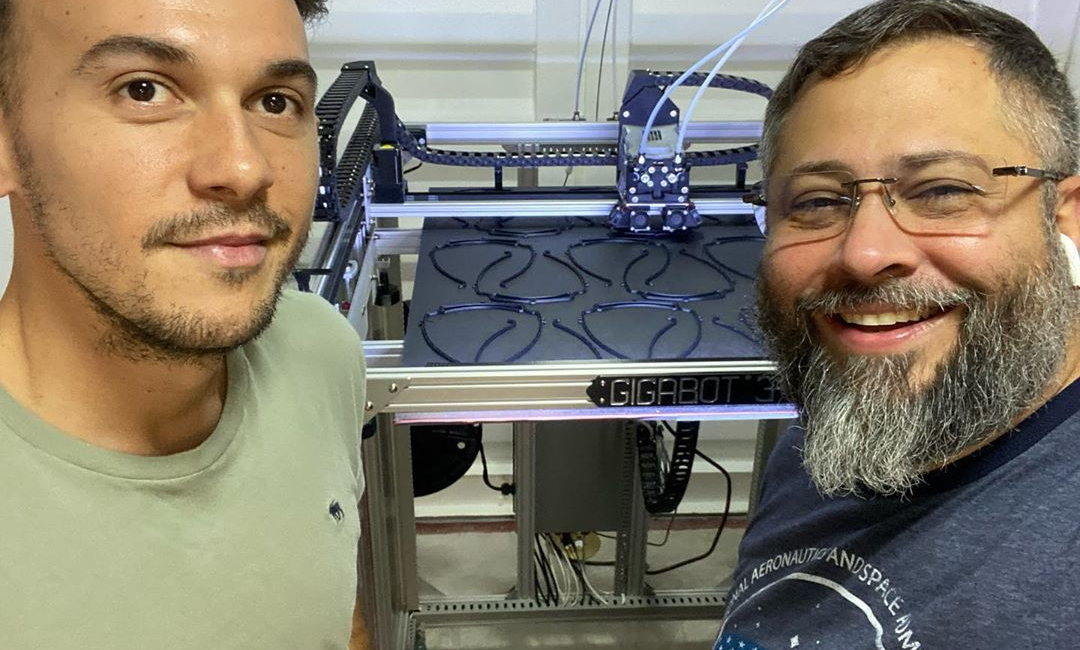

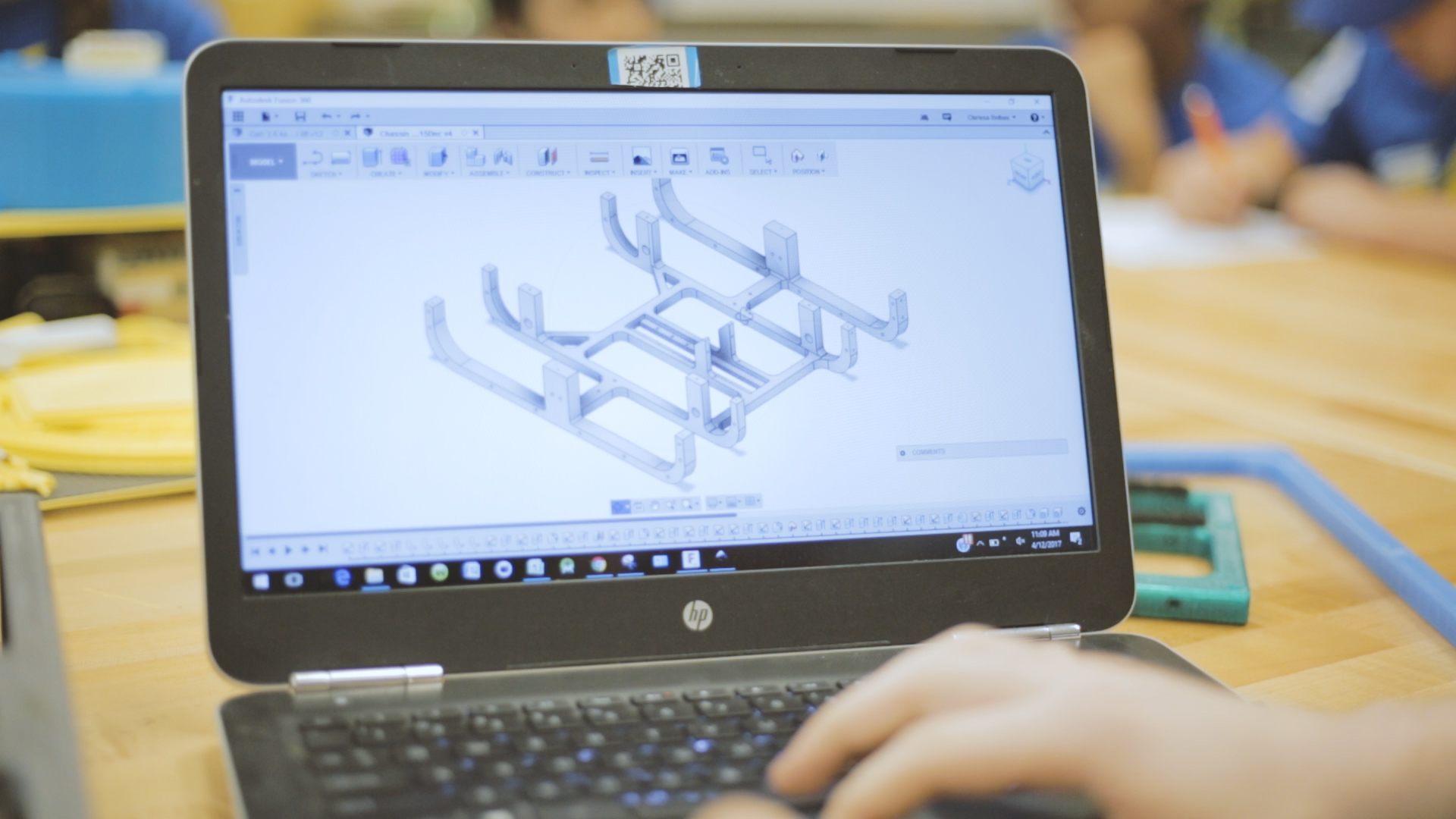

Now an engineer at Skylark Wireless, LLC, Kidd is committed to offering those opportunities to students. Recently, she joined a special project that offers eager young learners hands-on experience in applied computer science, electrical engineering, 3d printing and mechatronics and encourages them to focus on space innovation: the ISS Mimic.

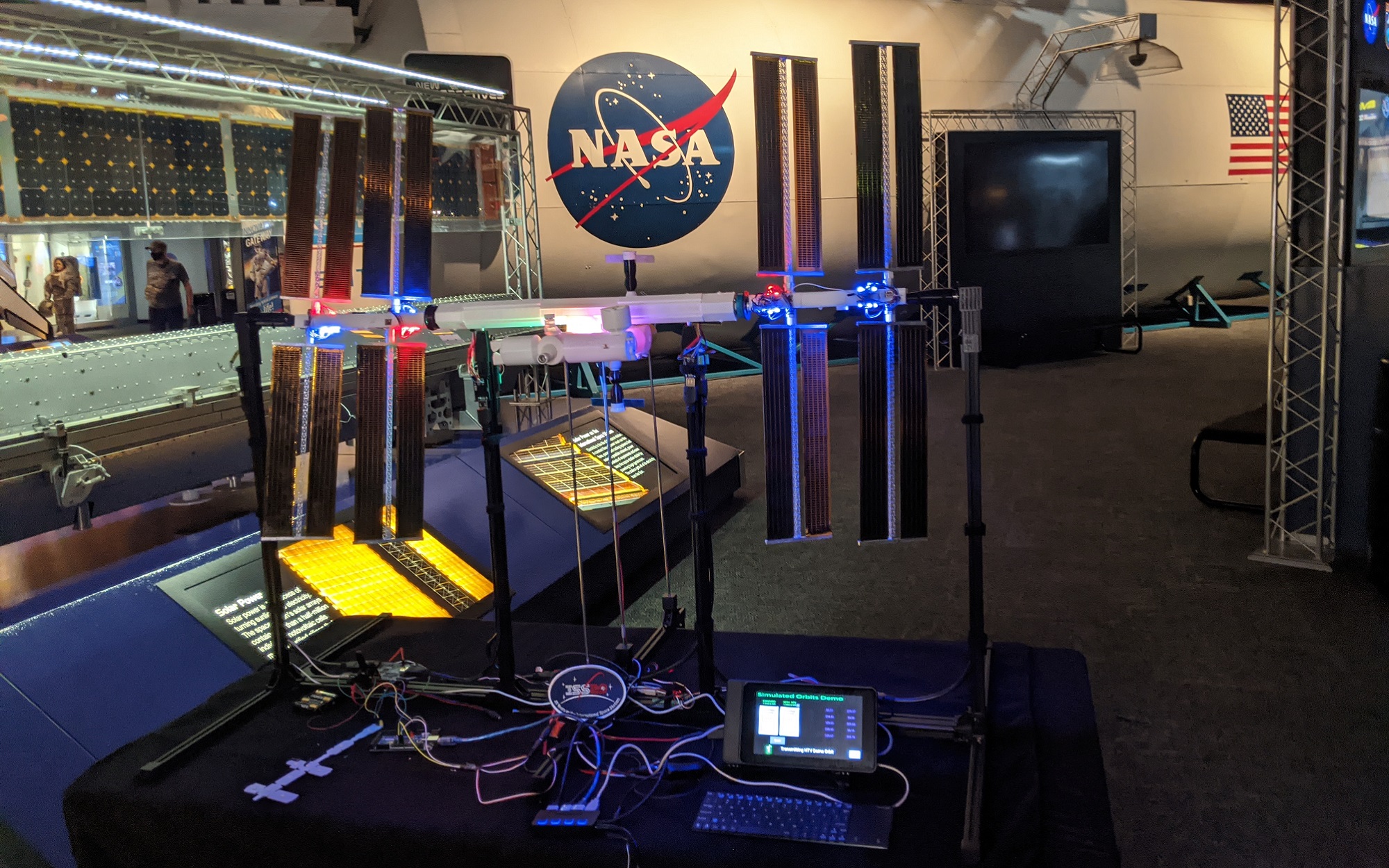

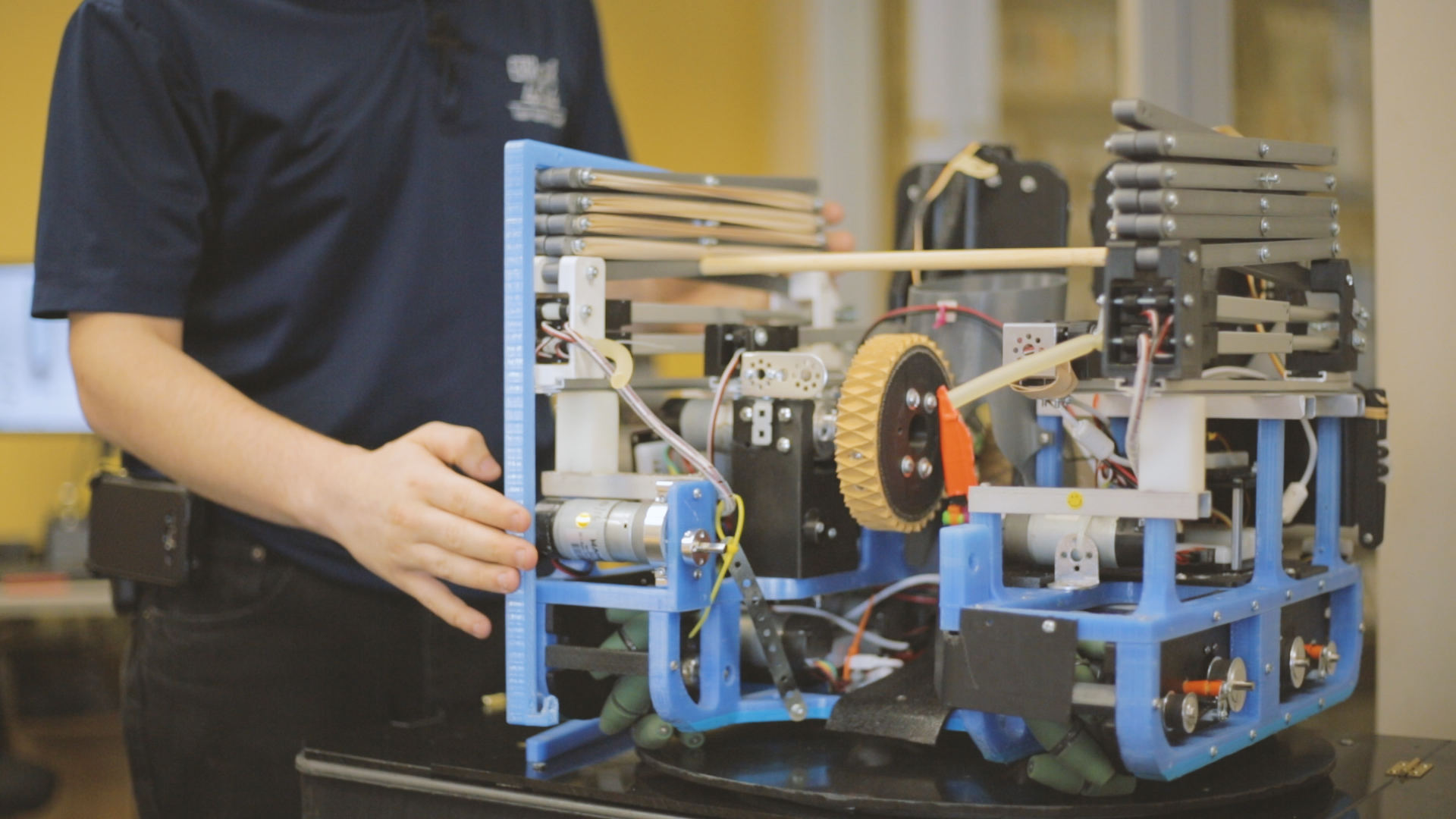

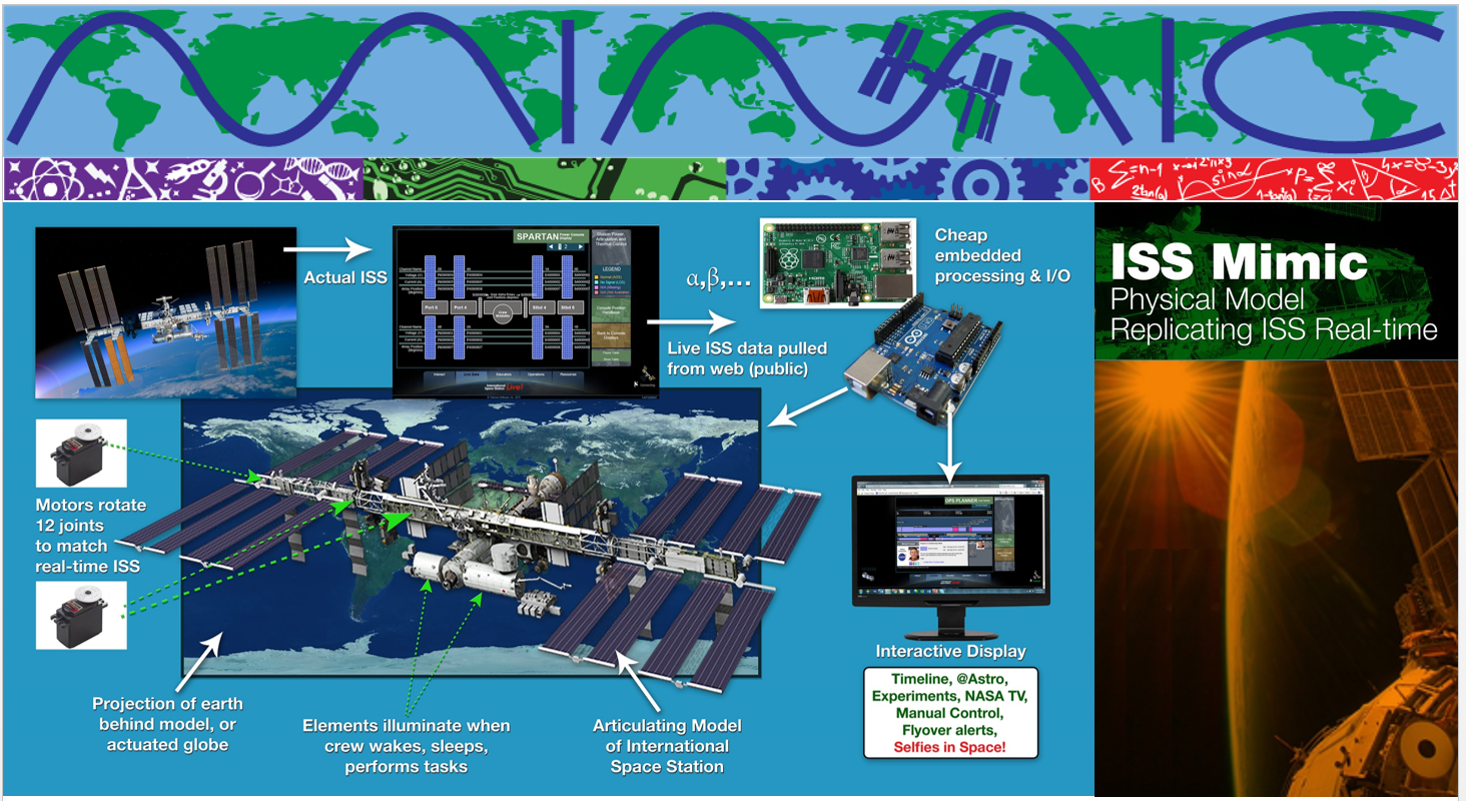

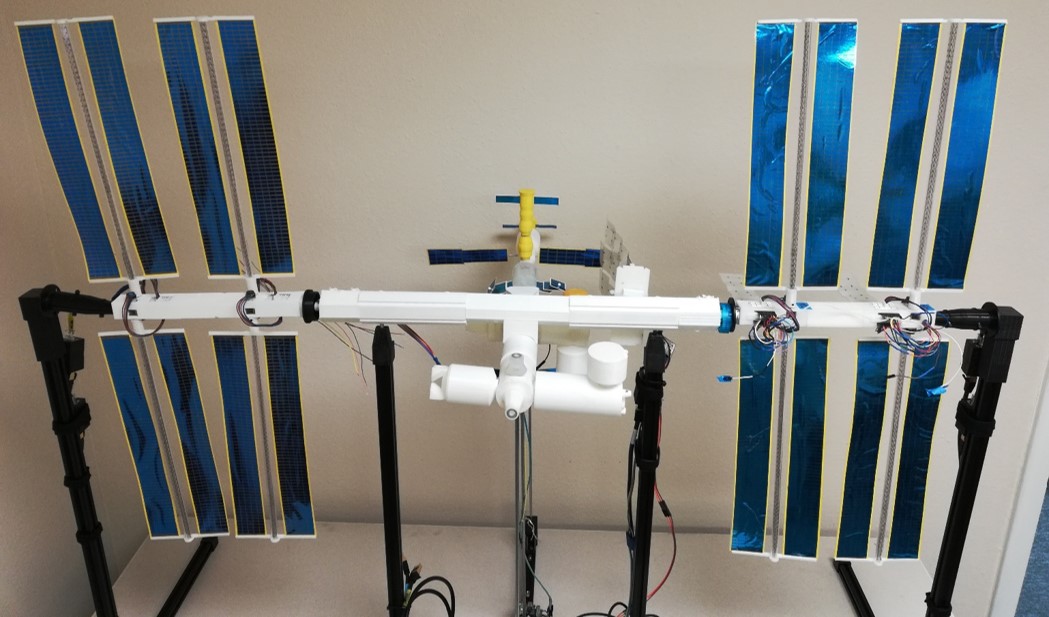

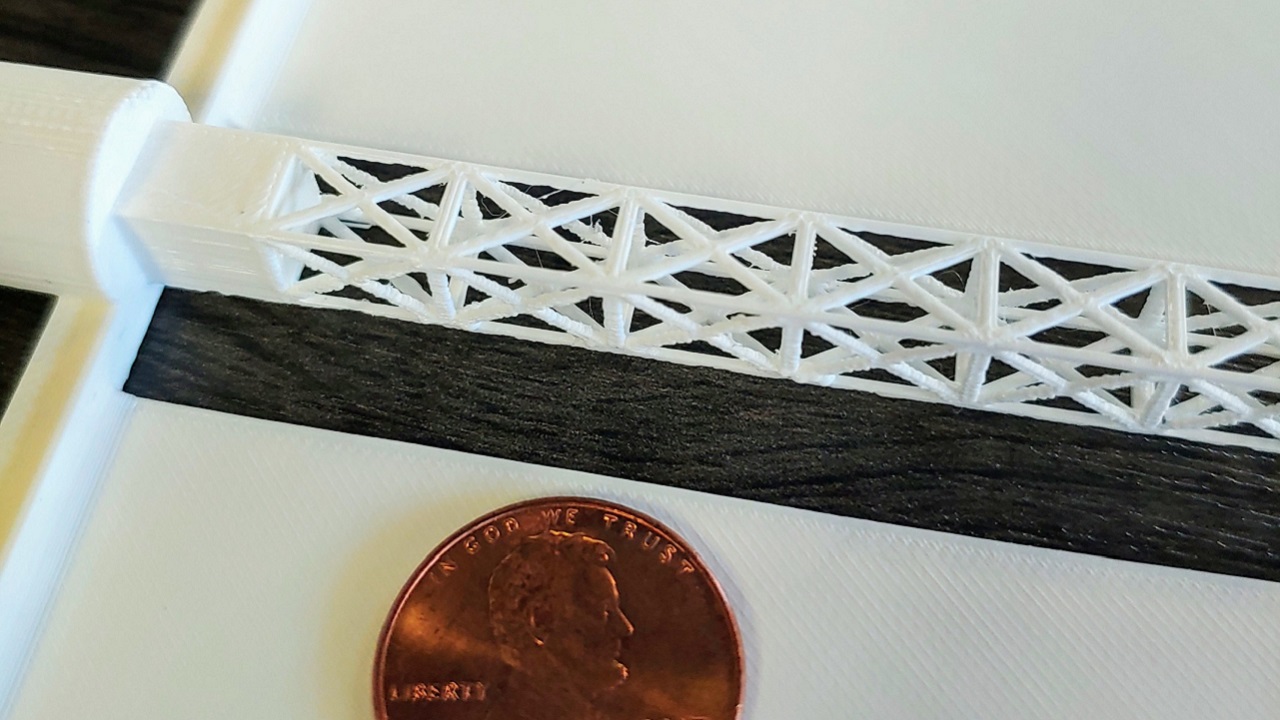

Five years ago, on the 15th anniversary of continuous human presence on the International Space Station (ISS), Boeing engineer Bryan Murphy proposed a STEM outreach project to his colleagues who work on the real space station. The idea: to create a 1% scale model of the ISS, complete with moving parts, that mimics in real-time the telemetry data of the space station that circles the earth every 90 minutes.

Murphy wasn’t the only one in the group who had discovered that NASA was constantly broadcasting live, publicly available data from ISS back to earth via ISS Live. The vast collection of data, including details on battery levels, solar array rotations, air lock pressure, and much more was available for anyone to use. Murphy and his teammates figured: why not bring the station down to earth in a desk-sized model that anyone could interact with? They decided to go for it.

Boeing is the prime contractor for the ISS. For over two decades, Boeing’s ISS team has provided round-the-clock operational support, ensuring that the full value of the world’s most unique and capable research laboratory is available to NASA, its international partners, other U.S. government agencies and private companies. So, for three and a half years following the conception of the ISS Mimic, the off-hours project progressed slowly alongside the engineers’ work supporting the space station and the mind-blowing scientific achievements emerging onboard. The primary project goals were keeping cost and complexity down to be educator friendly while maintaining the essence of ISS.

ISS Mimic steadily took shape, but it wasn’t until February of 2019 before they felt it was ready for public demonstration. They took ISS Mimic to a local high school to show students the moving model. But something was wrong. The live data stream – that important information ISS Mimic relied on to represent its big sister in the sky – had disappeared. “Everything worked until we got there[to the school], and we were like, ‘what’s going on?,’” recalled Craig Stanton, Murphy’s fellow Boeing engineer and ISS Mimic teammate. Without the data, they couldn’t demonstrate the live syncing, but could still show off the mechanics, control screen, LEDs, and 3D printed parts, so in true fail-forward fashion, they pressed on.

The interest from teachers and students was palpable. Though they’d done some small in-house show-and-tells, “it was the first time for us to take it anywhere,” shared Murphy. “For me, it was very motivational to finally be out there.” The team knew they wanted to move forward and get ISS Mimic in the hands of more teachers and students, but what had happened to the data from ISS Live?

The team went searching for answers, and the news was not good. Sam Treadgold of Boeing’s ISS team phrased it succinctly, “ISS Live got defunded – the public NASA telemetry suddenly shut down, and that was the major obstacle that inspired us to either give up the project or fight with everything, with all of our arsenal, to get it refunded.”

They thought the project was toast. It would have taken a major decision from NASA leadership to reverse the funding decision, but the tenacious team wasn’t ready to give up. They contacted everyone they knew who had vested interest in the STEM engagement and outreach benefits of the now defunct program. After a string of touches with decision makers, a fateful meeting with William Harris, the CEO of Space Center Houston, the public visitor center next to NASA-Johnson Space Center, brought forth Harris’ support, and the collective efforts were enough to get the funding restored. The data stream turned back on.

“Once we passed that hurdle, it was like the floodgates opened. Let’s go. Let’s do it!” shared Susan Freeman, who also supports Boeing’s space station program. ISS’s 20th anniversary was approaching, and NASA was interested in promoting the project to encourage public interest in ISS. The ISS Mimic itself was in a development state that it could visualize interesting changes on ISS in real time. “One of the data values is the pressure in the U.S. airlock. We monitor that data so our program can recognize when a spacewalk is happening,” said Treadgold, “ Last year, when a hole formed in one of the Russian vehicles, the pressure in the whole ISS started dropping, and our lights started flashing [on ISS Mimic]. There wasn’t a spacewalk going on, and we were aware of the leak.”

“That’s not usually publicly known when that’s happening. It’s usually announced a few days later when NASA makes the public report,” shared Stanton, “but this way, you’re looking at the live data stream, and all of a sudden, you’re just as in the know as the people in the operations room. How cool is that for people and kids at home!”

And it was becoming more than just an outreach project, they were discovering that this scale model was helping them understand the work they were doing on the real space station with more insight and more collaborative understanding of the challenges and quirks of the flying football-field sized spacecraft. “ISS is massive,” said Freeman, “I know only these tiny little pieces. That in itself is a humbling thing, to realize and accept that I’m not expected to know all of this vehicle. There is so much work done on ISS, and a lot of time you’re so focused on your little, tiny detail, that you don’t necessarily know what else is going on around you.”

Boeing’s Chen Deng, whose day job focuses on supporting the experiments on ISS, explained looking at ISS Mimic helped cut through misunderstanding about thermal needs of payloads. “By looking at [ISS Mimic], we realized it was at an angle where the payload was not getting any of the sunlight needed to keep its warmth or input from the station itself, and that really helped.”

The ISS Mimic team is in the process of building a second model for Boeing’s internal team in charge of “pointing” the solar arrays. The ISS Mimic can rotate its solar arrays 60 time faster than the actual space station, allowing the engineers to test and visualize their code before using it on the real thing. ISS Mimic can also “replay” previously collected data engineers use to assess and understand anomalies. “This is better than numbers on a screen or even CAD animations,” reflected Treadgold. “You see this and know exactly what’s happening.”

But beyond the functional model, of which they’ve replicated 80-90% of ISS, the team wants to use ISS Mimic to make the interface intuitive, easy to understand and exciting to build for students. To make it so easy to pick up that it’s like a LEGO build, and so inviting that it draws people in to an interest in science or space. “The hardest part to get right is STEM outreach,“ shared Doug Kimble of Boeing’s ISS team. “We need to get more students involved and excited about ISS. We need future astronauts; we need future female astronauts. We need more kids excited about STEM, and science and math, and this is one of the ways we can do it.” Showing students that the robots they’re crashing into each other in competitions use the same encoders, the same programming, the same motor drivers that are on the ISS Mimic makes it accessible and reinforces for students their own capabilities.

“We want these ISS Mimic models everywhere, in every airport, in every museum, in every school. Big dream,” declares Freeman.

“So people can see that they’re capable of this,” explains Murphy, “and have a real chance to play in this domain. It’s a means to let every disadvantaged kid know they can do this stuff, tinker in this field and see if they may want to turn this into more than a hobby one day.” It circles back to Kidd’s experience with a lack of role models. If the team can introduce the ISS Mimic to a student who hadn’t been exposed to the space program before, they might spark an interest the student didn’t even know was there. It might just set them on a path to a career which, for the members of the ISS Mimic team, is challenging, thrilling, and celebrates humanity’s greatest collaboration.

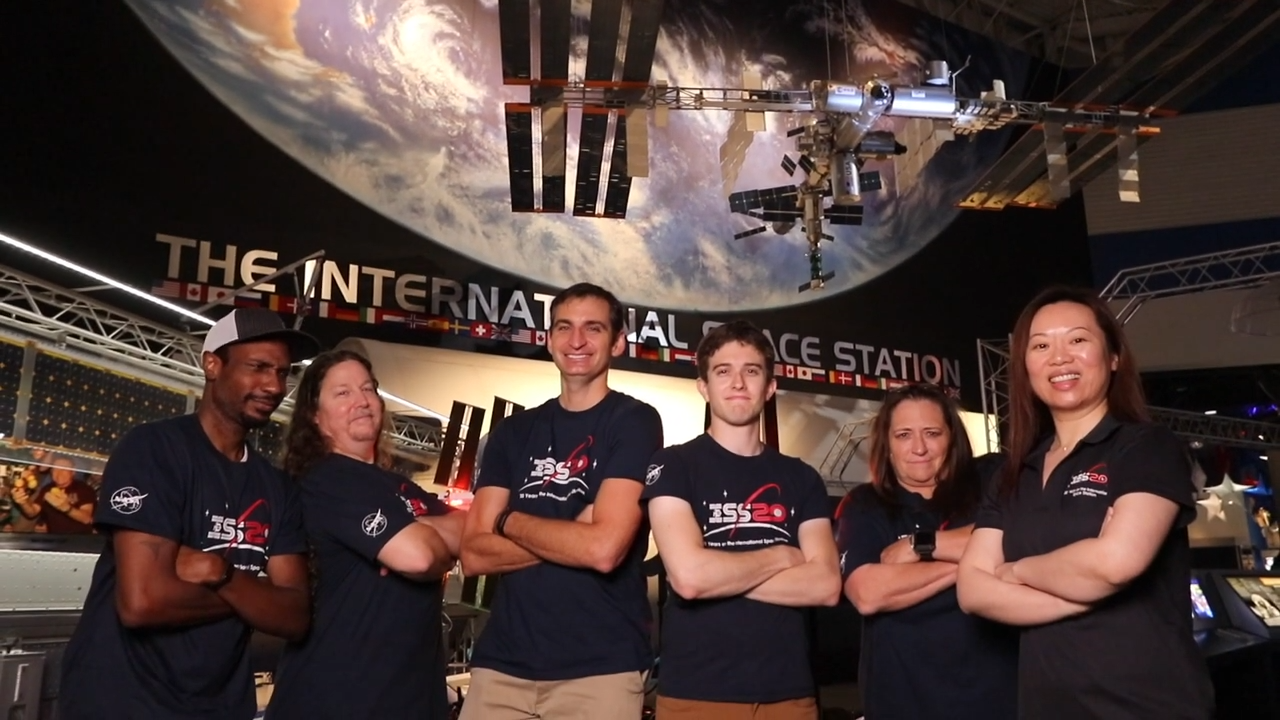

The ISS Mimic team includes:

Chen Deng

Susan Freeman

Dallas Kidd

Doug Kimble

Bryan Murphy

Craig Stanton

Sam Treadgold

Want to volunteer? ISS Mimic is looking for programmers, 3D modelers & educators to join the team! Reach out to them at:

email: iss.mimic@gmail.com

fb: https://www.facebook.com/ISS.mimic/

ig: https://www.instagram.com/iss_mimic/

twitter: https://twitter.com/ISS_Mimic

discord: https://discord.gg/34ftfJe

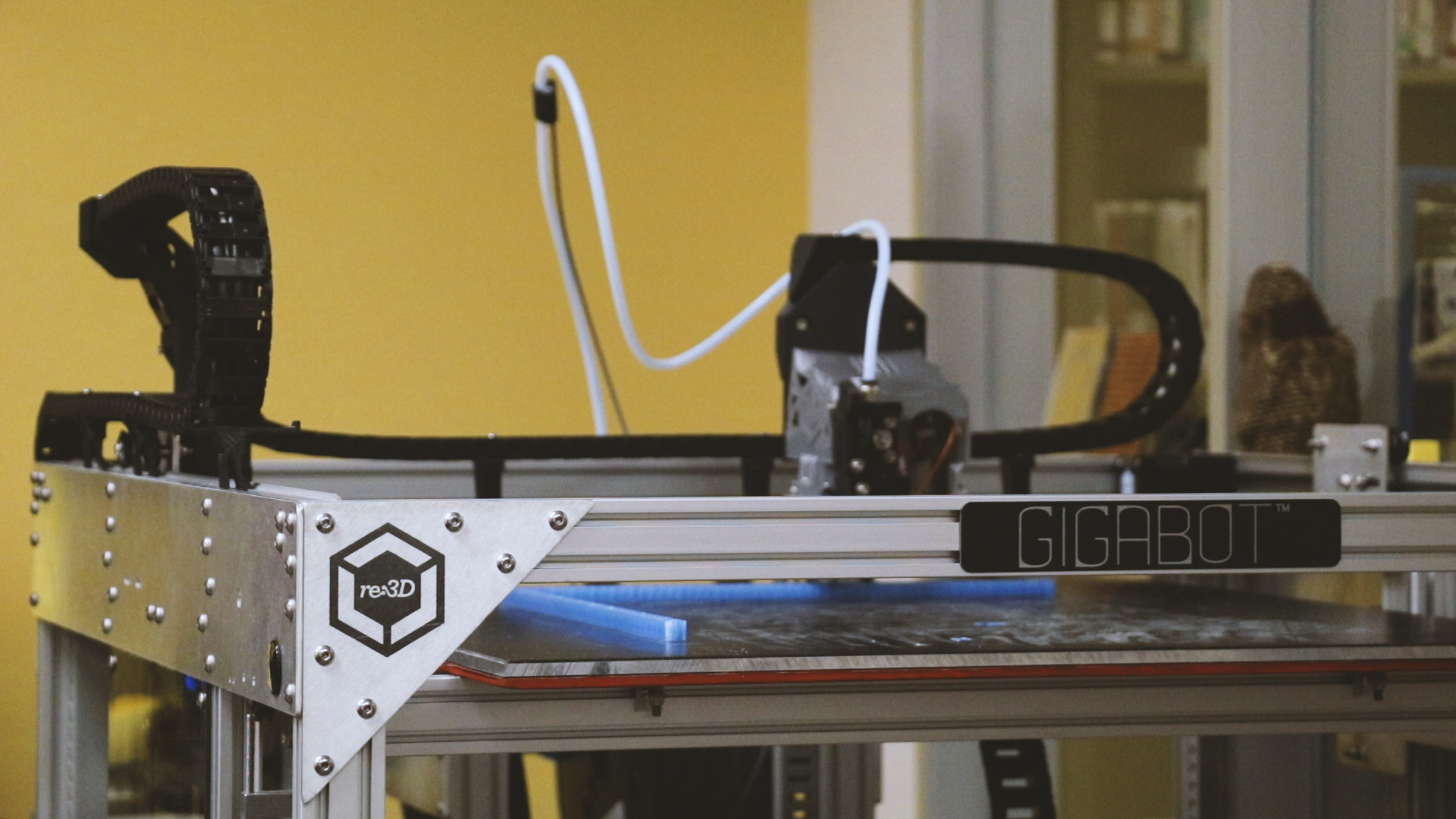

re:3D offers 3D printed ISS Mimic parts available at shop.re3d.org

Charlotte craff

Blog Post Author